A leasehold mortgagee doesn’t necessarily need to meet a financial test.

RANJAN SAMARAKONE

Anyone negotiating a ground lease knows it must be financeable, i.e., it must contain provisions that will induce a lender to accept it as collateral for a substantial mortgage loan. Those provisions are well defined. In a few recent ground lease deals, though, I’ve had some new discussions about what types of lender can hold a leasehold mortgage.

Traditionally, a lender that wanted to qualify had to be an “institution,” i.e., it was a bank or some other traditional financial institution. It also usually had to meet a financial test, such as net worth and liquidity. This was accepted in many ground leases as a required measure of creditworthiness, seriousness, and responsibility.

With increasing use of real estate funds, other funds, and other non-banks as lenders, property owners and tenants under ground leases should broaden their thinking about institutions.

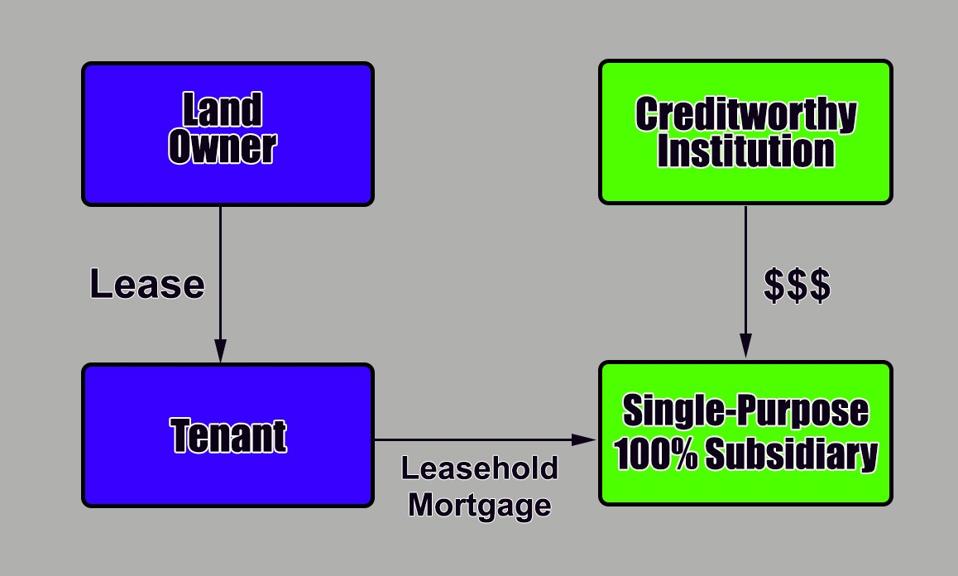

For example, a large fund may want to create a single-purpose entity to act as lender. That entity would be wholly owned and managed by its parent entity, a fund that clearly meets the financial test and is institutional, but the actual lender entity would not itself meet the test.

Similarly, a fund that wants to be a lender itself might not meet the financial test, but it might be part of a large group of funds that is of institutional quality and size. If the multiple funds in that group were put together, they would easily meet the financial test. But that’s not how funds work.

In response, ground lease negotiators need to rethink how they define and apply the requirement that a lender be an “institution.”

Intuitively, a property owner might always want the lender to be highly creditworthy because that’s always a good thing. If, however, one drills down into the workings of how a ground lease treats a lender, the lender’s actual creditworthiness does not matter much. The lender only rarely assumes any direct obligation to the property owner.

For the most part, a typical ground lease just gives the lender rights, but few obligations of a type that require a creditworthy lender. The lender has rights, for example, to receive notices, cure defaults (i.e., try to fix any lease violations), enter the leased premises, disapprove some transactions, and receive a replacement for the lease if it somehow goes away.

The property owner can’t force the lender to pay unpaid rent or spend money to cure defaults, but takes comfort because the lender has every incentive to do that to preserve its collateral. Incentives are great, of course. But a property owner would also like to know that the lender has the capacity to pay the rent if necessary and otherwise cure the tenant’s defaults. That drives financial tests for leasehold mortgagees.

A property owner should, however, generally be satisfied if the lender has access to the necessary funds as opposed to holding those funds itself. As a result, a reasonable property owner should usually be willing to treat as an institution any subsidiary of a parent company that meets the financial test, even if the subsidiary does not itself meet the test. If the lender chooses to cure any lease defaults, access to the parent company’s resources should suffice.

The sheer size of an affiliated group should also give the property owner comfort that the lender, as a member of that group, will behave in a deliberate, sensible, and institutional manner.

If the lender is itself a fund that doesn’t meet the financial test, but is part of a substantial group of funds, then it’s more complicated. Here, no parent company exists with resources that the lender could reliably draw upon if needed. Instead, a fund manager would probably step up to provide capital if the fund itself needed money to cure defaults. That creates some comfort, though not as much as would a wealthy parent company.

The property owner might, however, reason that if the fund group is substantial, i.e., the fund manager has total assets under management above a certain level, then the fund manager will probably behave responsibly, care about reputational risks, and find the money needed to cure defaults or come up with some other way to solve problems with the lease. For this type of lender, the financial test might very well look beyond the actual lender and instead require a certain minimum for the fund manager’s assets under management.

That all makes sense until a noncreditworthy lender wants to do something where creditworthiness matters. For example, a noncreditworthy lender cannot expect to hold significant insurance proceeds or a significant condemnation award. Someone else will have to do it.

As another example, a lease might give a lender special rights or extensions of time but only if the lender agrees to fully cure whatever default the tenant committed. Under such circumstances, if a lender is not creditworthy it would need to deliver a guaranty from an entity that meets the financial test. That would also apply in the handful of other contexts where a lender might incur obligations to the property owner and doesn’t just have rights.

If any lender ever needs to take over completion of a development project, the property owner might care as much about development competence – and engagement of a qualified development manager if necessary – as it does about pure financial strength.