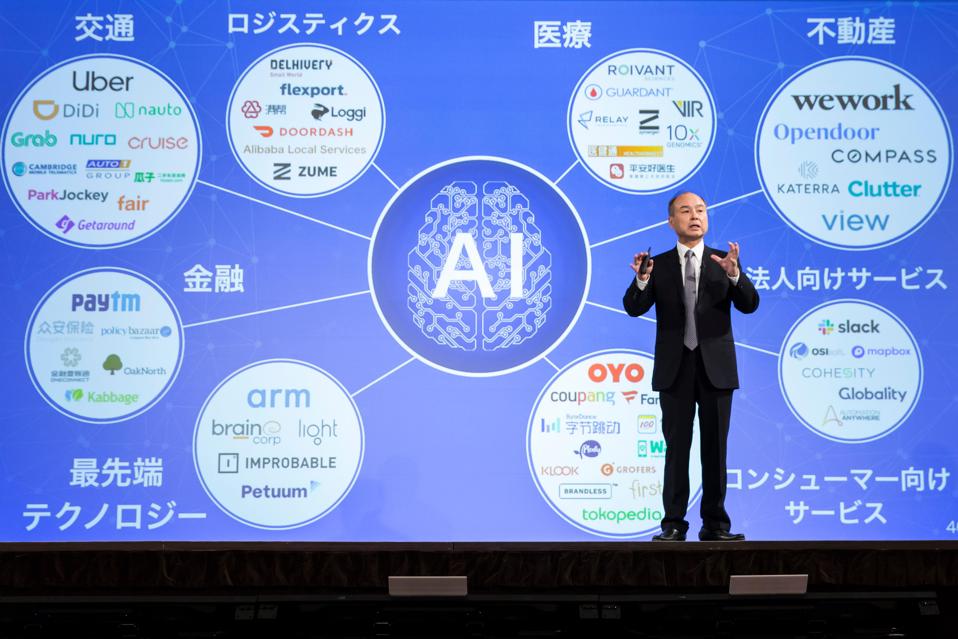

Masayoshi Son speaks during a press conference on May 9, 2019 in Tokyo, Japan. SoftBank Group announced its financial results for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2019 today.

Tomohiro Ohsumi/Getty Images

Masayoshi Son’s radar clearly isn’t what it used to be.

Back in 2000, the SoftBank founder did more than help create China’s most important startup. The $20 million he handed Jack Ma also made Son’s reputation as venture capital guru—the “Warren Buffett of Japan,” as he was dubbed. When Ma took Alibaba public in 2014, Son’s stake had swelled to $50 billion.

This reputation is now taking a big hit as WeWork essentially implodes before our very eyes.

Twelve months ago, Son couldn’t heap enough praise at the office-rental startup Adam Neumann cofounded. Son claimed that WeWork is the “next Alibaba” as he raised his stake. By January, Son’s $100 billion Vision Fund had piled nearly $11 billion into WeWork, which his team valued at $47 billion.

Recent days haven’t been kind to Son’s bet. Raging questions about its business model–and plunging valuations—forced WeWork to shelve a hotly anticipated initial public offering. Now, the company’s directors are reportedly looking to shunt CEO Neumann aside, not unlike how Uber sidelined Travis Kalanick.

All this leaves Son with some difficult explaining to do as he cobbles together a second $100 billion VC fund.

Son’s initial fund is essentially a leap of faith on his gambling skills. His big win on Ma’s Alibaba led him to another headline-making success on Singapore’s GrabTaxi. The $250 million he handed to cofounder Anthony Tan baffled many at the time. Now, Grab is the dominant ride-sharing power in Southeast Asia. WeWork, though, is a notable stumble—one that calls into question Son’s entire strategy.

How the “Sage of Tokyo” missed that WeWork is essentially a leveraged property investor whose fortunes are tied to real estate market zigs and zags is anyone’s guess. The glitzy office designs and free-flowing coffee and beer make it easy to forget WeWork’s similarities to McDonald’s. Just as the burger giant’s real business is scoring good land deals for franchisers, WeWork is largely concerned with winning prime locations. Not very “new economy,” is it?

Pundits are exploring how costly an error this might be for Son personally. With his $20 billion-plus fortune, Son is increasingly betting on himself. He put up 38% of his SoftBank stake as collateral for personal loans from 19 banks. This enabled him to gamble his vast wealth without diluting his corporate control. Yet it also amplifies his personal risk if SoftBank shares plunge.

The real focus should be reconciling how Son’s scattershot strategy makes sense. Since 2016, he’s dabbled in everything from microchips to solar panels to satellites to indoor farms to robots to e-commerce startups to investment banking. He commandeered both the ride-sharing space and the shared-office hive genre. It remains to be seen how this Island-of-Misfit-Toys approach amounts to a workable strategy that can be repeated.

Prudence counsels slowing down. Before deploying another $100 billion of firepower, Son should circle back to the first. Son hasn’t just reinvented Silicon Valley’s VC game–he’s also morphed into a one-man bubble-blower. He’s developed quite the reputation for arguably overpaying for some startups from online lender SoFi to robot-pizza-maker Zume to food-deliverer DoorDash. And for tolerating questionable corporate governance structures. The power Neumann would wield over WeWork is a case in point.

Adam Neumann speaks onstage during WeWork Presents Second Annual Creator Global Finals at Microsoft Theater on January 9, 2019 in Los Angeles, California.

Michael Kovac/Getty Images for WeWork

Perhaps that’s an appropriate means of searching for the “singularity,” that moment when artificial intelligence surpasses humans. Perhaps Son’s claim that he has a 300-year vision affords him with a benefit of the doubt most investors don’t enjoy. Yet if Son doesn’t tread carefully these next 300 days, his Vision Fund 2 is in for a sudden dose of gravity.

Already there are signs of financing gaps. There’s appears to be a dearth of huge cornerstone investments from Saudi Arabia—which ponied up $45 billion for the Vision Fund 1—or others. Son’s reported plan to lend SoftBank employees as much as $20 billion so they can invest in Vision Fund 2 smacks more of desperation than foresight.

There also are valid worries about where Son might aim his next $100 billion. The best minds in Silicon Valley are more focused on helping platforms sell ads than dreaming up new game-changing advancements. The pipeline of future “unicorns” and easy targets may not be what Son encountered in 2016. Nor is it clear Chinese innovators can fill the void anytime soon. Or, for that matter, Son’s native Japan, which has produced half as many tech unicorns as Indonesia.

In this sense, Son’s WeWork misfire could scarcely come at a worse time. For all the Buffett-of-Japan chatter, Son has yet to stabilize Vision Fund returns in the Berkshire Hathaway sense. Buffett’s General Re is a vital shock absorber, offering steady income no matter where else Buffett is exposed. In early 2018, Son toyed with taking astake in Swiss Re. He decided against it, only to double down on WeWork.

There’s still plenty of time for Son to live up to his Buffett-sized rep. Doing so, though, means prioritizing the next 300 days above the next 300 years.