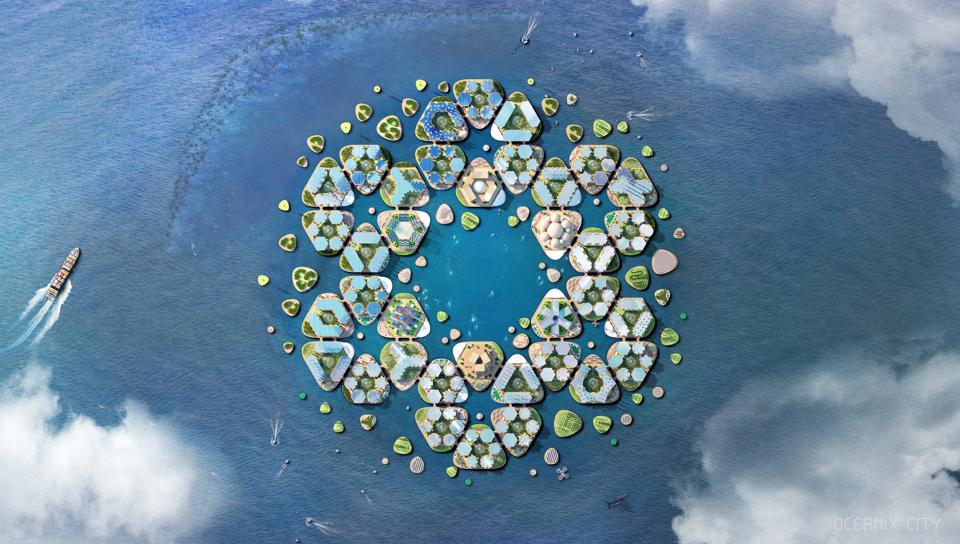

Render of the Oceanix city concept.

OCEANIX/BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group

“Coastal cities are literally the interface between man and nature. That is where it is happening,” spoke Marc Collins, the former tourism minister of French Polynesia and founder of Oceanix as we sat together in Bryant Park beneath the towers of Manhattan. Collins has a crazy dream: to build floating cities all over the world. I listen to him not just because I enjoy wild ideas and quixotic endeavors, but mostly because I know that he is probably right: for communities facing rising sea levels and municipalities looking to cash in on creating new coastal property, the sea is the final frontier.

Humans have always been drawn to the coast to build our cities, but today this draw has increased to epidemic proportions, as two to three million people globally migrate to cities each week, with coastal cities now containing over 50% of the world’s population. According to UN Habitat, by 2035 90% of all megacities — cities with over ten million people — will be on coastlines. This is where the high property values are, this is where the bulk of economic opportunities are, and across Asia governments have been going gaga over further developing their coastlines — even going as far as artificially creating massive amounts of new waterfront property via land reclamation. Meanwhile, sea levels are rising at an ever-accelerating clip, and many coastal cities — even entire island civilizations — are in danger of being washed away within the next century.

We have never before had as much data to demonstrate an unnatural increase in the rate of sea level rise as we do now. According to a 2018 study published in PNAS, sea levels have been rising at a .118” per year clip since 1993 and NASA data shows that this rate is accelerating, conservatively predicting a 26” rise by 2100. This spells havoc for the 600+ million people who live in low-lying coastal areas around the world.

The bill for rising sea levels is already being served. Louisiana has set aside $25 billion for a new coastal master plan, Texas has invested $11.6 billion in a storm surge protection system, and New York City devised a $3.7 billion coastal defense plan in addition to a $10 billion proposal to artificially expand the surface area of Manhattan to hold off the encroaching sea. Altogether, it has been estimated that it’s going to cost the USA alone around $400 billion over the next two decades in sea level rise damage control. Globally, Indonesia has already announced a $34 billion plan to move its sinking, flood-prone 30-million-person capital to higher ground, the South Pacific is estimated to need to spend $775 million annually (2.5% of GDP) to fight against sea level rise, and Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines are expected to shell out 6.7% of their collective GDP by 2100 in coastal flooding prevention plans. Meanwhile, the UK National Oceanographic Centre (NOC) discovered that the global cost of the damage caused by rising sea levels could be in the ballpark of $14 trillion annually before this century is out.

“If we don’t reverse climate change we’re going to pay the cost of adapting to it,” exclaimed Dr. Tom Goreau, the president of the Global Coral Reef Alliance. “There are billions of people living on coastlines that are going to be flooded. It’s going to be worse and worse and worse year by year and they are going to have to move eventually, and where are they going to move to? Either we’re going to have to deal with that on a large scale or we’re going to have to move out into the ocean.”

Professor Goreau was not speaking in jest. As evidenced by a high-level UN Habitat roundtable event that occurred earlier this year in New York City — which featured a Nobel-prize winning economist, CEOs of major tech firms and oil companies, university professors, climate change thought leaders, and even a movie star — the idea of human settlements being created on the ocean has transitioned from science fiction to present day reality. Waterworld is here, and floating cities are being seriously proposed as a way forward in an age of climatic vertigo.

What are floating cities?

Render of the Oceanix City concept.

OCEANIX/BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group

Floating cities lose a little clarity in their nomenclature. When we talk about floating cities we’re generally not really talking about entire cities floating around on the open ocean, but a series of interconnected platforms that are moored to the seabed a short distance out from shore.

Such floating settlements are not a new concept, as people all over the world have been building and living in them for thousands of years. From the 13,000-person settlement of interconnected platform houses at Kampong Ayer in Brunei to the boardwalk-linked floating fishing villages around Jakarta; from the stilt homes of Iquitos, Peru, that rise above the Itaya River to the floating slum of Makoku in Nairobi to waterborne settlements in Cambodia and Vietnam, when the land in highly-sought coastal areas is occupied people have always built out into the sea.

In more technical societies, the idea of floating cities has been floating around since the mid-20th century. In 1967 Buckminster Fuller was commissioned by a wealthy Japanese businessman to build a floating city in Tokyo Bay. Calling it Triton City, Fuller produced a model in collaboration with the MIT Center for Ocean Engineering that was essentially a ten-story tall tetrahedron built on a platform that was to be anchored to the sea floor. The engineering was apparently sound, and the model demonstrated that the floating city was, in fact, feasible. However, the project never came to fruition — the Japanese businessman passed away before it could be built and the project died with him. However, the administration of Baltimore caught wind of the idea and invited Fuller and his team to resurrect the project and build a 100,000-person version of Triton City in the bay outside their city, but an inopportune election loss booted the project’s primary backers out of office. In the end, Triton City ended up being a wild dream best represented by a scale model that Lyndon B. Johnson nicked from the White House and put on display at the LBJ Library in Austin, Texas, where you can visit it today.

In more recent times, floating cities haven’t been any less idealistic. The Seasteading Institute was formed in 2008 by former Google software engineer Patri Friedman — the famed economist Milton Friedman’s grandson — and the controversial Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel, who seeded the project with a $1.7 million investment. Their goal was to create floating cities outside the realm of government control as a way of cultivating independent libertarian utopias. Thiel described the project as offering an “escape from politics in all its forms” and attracted a following of passionate idealists, zealots, and wing nuts, who would come to indelibly brand the concept of the floating city in their image.

“Part of the problem [with floating cities] is that a lot of it has been focused with people who have their own agendas,” Goreau explained. “They want to be the kings or the princes or they want to have pirate radio stations or they want to have tax shelter schemes. So it’s been discredited by people who had dishonorable motives.”

In popular culture, floating cities pop up in the works of writers like Aldus Huxley and Francis Bacon, and, of course, there’s the 1995 movie Waterworld, which stared Kevin Costner as an over-evolved, gill-equipped, web-toed fish-man living in a dystopian world where sea levels rose above land, forcing humanity to gather on massive oil rigs controlled by post-apocalyptically-attired gangs. I asked Peter Rader, the co-writer of Waterworld, what he thought about the fact that floating cities — his sci-fi vision from the 20th century — could become a reality in the 21st.

“We are futurists when we write sci-fi,” he began. “When we create in Hollywood, the visions of the future tend to be a little more dystopian. When you go to a movie you’re paying your $15 ticket for a 90-minute experience, so it can be bleak and dark, and then you’re out of there, you’re back to your ordinary life. But we don’t want that dark, bleak version of the future, where it’s like a rusting, subsistence existence.”

Perhaps ironically, it’s floating cities that are driving humanity to counteract that bleak and rusting cinema-induced vision of the future.

Solutions or half-measures?

Nearly all coastal cities are currently facing issues with rising sea levels and flooding, and many have devised strategies to curb the impact and buy themselves a little time. Some cities have proposed multi-billion dollar plans to erect massive seawalls around their coastlines, others have proposed artificially raising the land, while still others have begun charting out plans for a managed retreat. Ultimately, all of these solutions are primitive, outrageously expensive, and half-measures at best.

“If you talk to anybody who knows about marine walls, they say there’s two types of walls: the walls that have fallen into the ocean and the ones that are going to fall into the ocean,” Collins explained.

As far as managed retreat goes — i.e. throwing in the towel and moving affected populations to higher ground — we only need to look at Indonesia to see how real of a solution this has become. In April, the country announced that it plans to move its capital to Borneo, citing the chronic flooding of Jakarta due to groundwater extraction and rising sea levels as the reason. A third of the 118 islands of French Polynesia may soon endure a similar fate, as somewhere between 2040 and 2060 they are slated to be submerged.

“What do we do when an entire people spread out through the Pacific — and maybe around the world — no longer have a land to call their own?” Collins questioned. “This is not a small thing.”

Blue Frontiers

Finding all three of these potential band-aids for rising sea levels inadequate, Collins, an entrepreneur who has started over 20 companies, began looking into other solutions. He wondered if people could simply build and live on portable infrastructure that could be built over the sea and rise with sea levels? The models for Fuller’s Triton City and the experiences of indigenous people all over the tropics told him that it was possible, so he reached out to the Seasteading Institute in 2016 and invited them to French Polynesia.

The project was dubbed Blue Frontiers, and was to be a floating special economic zone that would have different tax, customs, immigration, and labor regimes than the rest of the country, and would be funded by the sale of its own cryptocurrency. In other words, it was to be the quintessential libertarian utopia — where people with big money and even bigger ideas could come and, as they put it, live free. While Blue Frontiers did sign an MoU with the Frech Polynesian government in 2017, the floating special economic zone was never to be. Like in Baltimore a half-century before, the government backed out at the eleventh hour.

Oceanix City

Oceanix City.

OCEANIX/BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group

From the ashes of Blue Frontiers, Collins started Oceanix in partnership with the architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group, a company that would design floating cities that could be deployed in varying contexts around the world. Collins hired a team researchers at MIT who were actually the students of the professors who worked on Fuller’s Triton City, and began hashing out plans for what they called Oceanix City.

Oceanix City would essentially be a 10,000-person settlement made up of an array of platforms that would be prefabricated in a factory, towed out to sea, pieced together like Legos, and attached to the seabed with bio-rock — a sort of quasi-living building material that would essentially turn the entire city into an artificial reef. The main building material for structures would be laminated bamboo beams, which could be grown on floating outposts. Water would be derived from desalinating seawater and harvesting the humidity in the air. Food would be grown on-site, and all residents would be encouraged to eat a plant-based diet.

The fundamental design principle of Oceanix City revolves around the idea of bio-mimicry, “where you look at nature and go, how does nature figure this stuff out?” as Collins put it. Like the traditional homes of French Polynesia, nothing about the place is designed to be fixed or permanent — all materials can be easily replaced and recycled, and, if the decision is made to move the city, it could, theoretically, be taken apart and towed away to another location.

Collins contrasted what he planned to do with the skyscrapers that surrounded us. “You look at any of these buildings behind me; the effort, the energy, and the materials, the costs, the carbon … that took a long time to put together, and the idea is that it will be here forever. We now realize that nature is encroaching. It’s coming back. It’s taking over.”

Conclusion

50 years ago floating cities would have seemed as ridiculous as the movie Waterworld. Oceanix City should probably be relegated to the back pages of science fiction, and it should come as a blow to the collective human ego why dreamers such as Marc Collins are now being taken seriously. We are clearly entering new times, where 30-million-person capitals are being moved to higher ground, where cities are earmarking tens of billions of dollars to wall themselves off from the sea, and entire island civilizations are going to have to, almost literally, sink or swim.

“Floating cities are a worse case scenario,” Goreau admitted. “I prefer that we solve the fundamental problems and reverse global climate change, but that means sucking the CO2 out of the atmosphere and going back to pre-industrial levels. But governments are not there. If our politicians don’t get smart and don’t start solving our long-term problems then we don’t have a choice but to start getting floating cities.”