Housing construction increased the last two years, but after several years of underbuilding we are not overbuilt but closer to supply-demand balance. This article looks a the United States as a whole. Regions have very different patterns. However, the approach of this article provides a template for looking at a local housing market.

Although many people are most interested in single family homes, competition from apartments must be understood to get a full picture of the forces impacting housing prices.

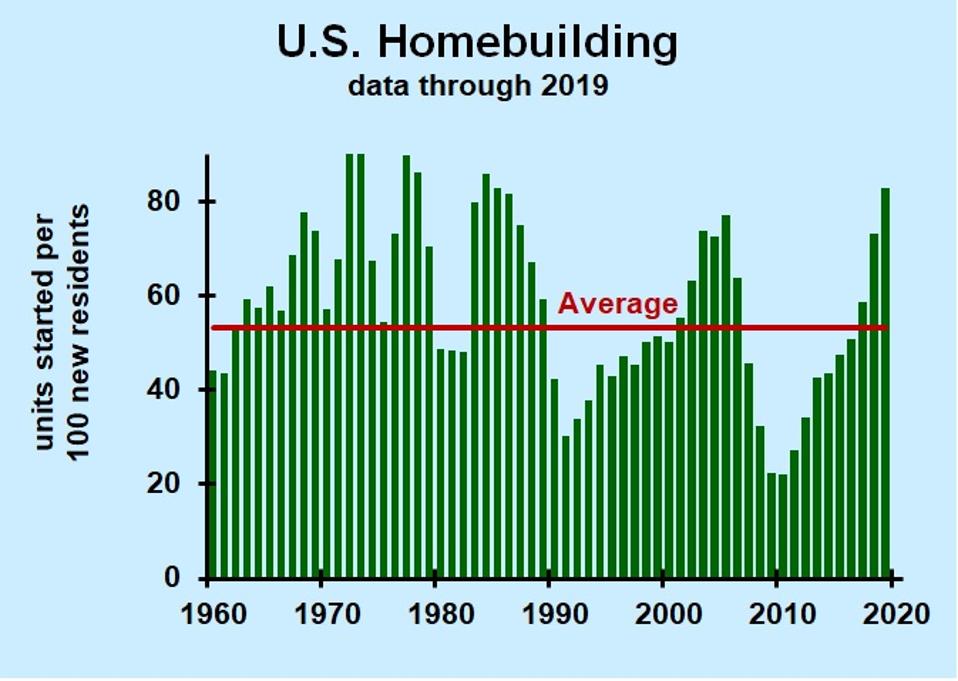

How much housing we are building relative to population growth is the most important factor to examine. It makes little sense to compare new construction last year to new construction in the 1960s, if anything has changed. And yes, a lot has changed. Some people compare new construction to the total population, which is a step in the right direction. However, housing lasts a long time. I have been a guest in houses built around 1800, so a house can last. The best first approximation is to look at housing relative to the change in population. We live about 2.5 people per household, so we might need about 40 new housing units per 100 new residents if housing lasted forever. The actual historical average is 56 new housing units per 100 new residents.

Ratio of housing units started to population growth.

Dr. Bill Conerly from Census Bureau data

This 56-unit average is higher than the 40-unit nominal need because of some demolition and abandonment of the old housing stock. (Many rural areas are losing population, especially in northern states, while cities in warmer climates grow. Those abandoned farm houses cannot be moved to Houston or Miami despite the need for more housing in the fast-growing metropolitan areas. The ratio of new building to population growth also reflects a change in how we live. Many older people used to live with their adult children, but now have stay in their own houses or apartments.

The last two years, homebuilders have exceeded new underlying needs, though they responded to signals of past under-building. Those signals, of course, were rising home prices and apartment rents.

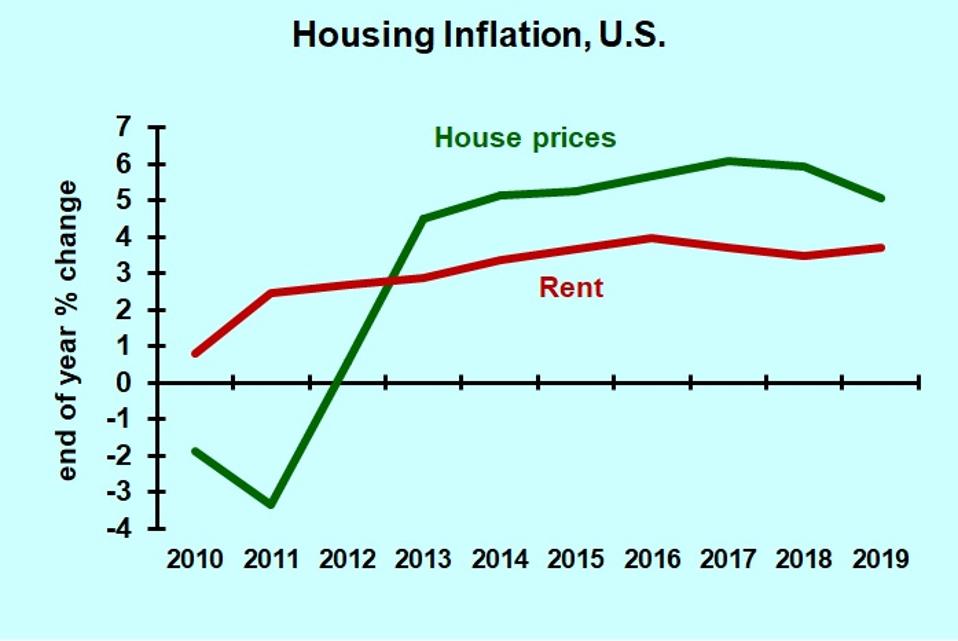

Housing costs have been rising faster than overall inflation, but at fairly stable rates of gain. The latest four-quarter change in price for existing home prices was 5.1%, not much different than in recent years. Residential rent increased by just under four percent, pretty steady over the past few years.

Housing inflation, U.S., 2010-2019

Dr. Bill Conerly based on data from Federal Housing Finance Agency and Bureau of Labor Statistics

Rising housing costs are a natural result of limited land available for development in many areas, as well as low productivity growth in the construction sector. While manufacturing output per worker has increased substantially, not much has happened in construction output per worker.

Vacant housing units, both apartments and single family homes, tell a story of market tightness. Vacancy data are imperfect. For example, the quarterly data shown in the accompanying chart does not align with the decennial census or other vacancy counts. Nonetheless, the changes over time probably provide a ballpark estimate. Rental vacancy is now the lowest since 1985. (Rental vacancy covers both apartments and single family homes offered for rent.)

Owned property, mostly single family homes, reached the lowest vacancy since 1980 in spring of 2019, and has since ticked up a tiny amount. So both vacancy series support the tight-market hypothesis.

U.S. Housing vacancy rates, 1980-2019

Dr. Bill Conerly based on data from Census Bureau

Mortgage interest rates have dropped sharply as of this writing. Cheap credit helps housing in the short run, but in the long run it does little. Demographics drives demand. Low interest rates enable families to buy houses, or move up to more expensive housing. But low interest rates also help developers build more apartments. Net-net, lower interest rates probably shift demand toward single family homes and away from apartments, but with relatively little impact on total housing demand.

Looking forward through 2022, job growth should continue to push consumer incomes up, enabling more people to have their own housing, whether that be owning a house or having an apartment without unrelated roommates. Interest rates will remain low for a while. Many of the regions into which people would like to move are unable to add too many housing units, because of political restrictions on development or the tight supply of construction workers.

Although this analysis focuses on the nation as a whole, the most dominant trend recently has been the divergence between tech and finance centers—Silicon Valley, New York, etc.—and regions with more open real estate development attitudes. Look for that dichotomy to continue, with Texas and Florida building more housing, while California and the urban northeast will see continued rising housing costs due to limited new supply.