Many real estate investment vehicles take the form of Delaware limited liability companies, with two types of members. First, there is the sponsor of the deal – whoever found the property, negotiated the acquisition and financing, came up with a plan for upgrades and operations, and will call most of the shots during the life of the investment. Second, there are passive investors who contribute most of the equity capital needed for the acquisition.

A recent Delaware case explores the limits of a sponsor’s authority, and conversely defines the point at which a passive investor can legitimately complain about whatever the sponsor did.

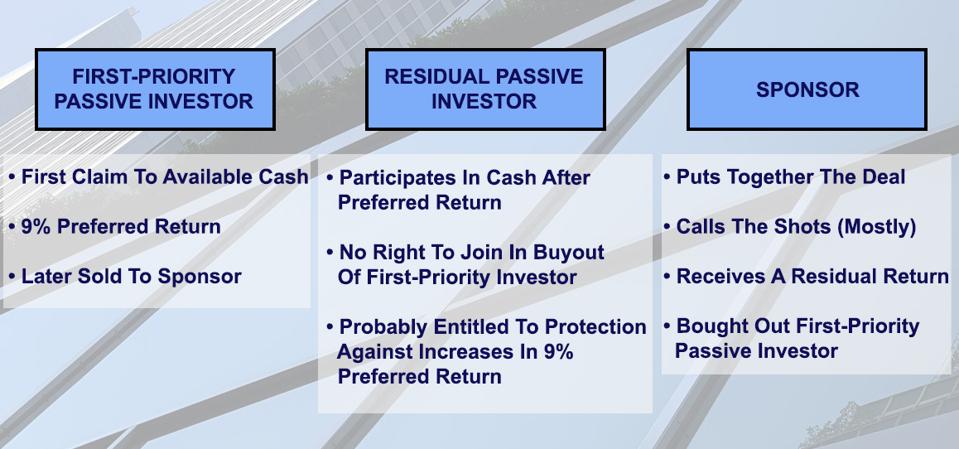

The LLC at issue in the litigation had two categories of passive investors: a first-priority passive investor who would receive a 9% preferred return before anyone else could receive anything; and a residual passive investor who, along with the sponsor, received a formulaic share of whatever was left over after the first passive investor received its 9% preferred return.

The first-priority passive investor wanted to exit the investment, so the sponsor acquired that investor’s interest in the deal. Then the sponsor unilaterally amended the limited liability company agreement to change the 9% preferred return to 12.5% and to lower the standard of care required of the sponsor.

Three investors in a Delaware LLC and how it didn’t work out.

Ranjan Samarakone

Soon after that, the sponsor arranged for the limited liability company to sell its investment. After payment of the mortgage, the remaining sales proceeds went entirely to the holder of the 12.5% preferred interest – i.e., the sponsor and a new investor the sponsor had brought into the deal. That left nothing at all for the residual passive investor.

The residual passive investor sued, alleging among many other things that the sponsor wronged the residual investor in two ways. First, the sponsor should have allowed the passive investor to participate in the sponsor’s purchase of the first-priority investor’s interest in the deal – because that opportunity belonged to the limited liability company and not just the sponsor. Second, when the sponsor increased the preferred return from 9% to 12.5%, that wrongfully reduced the value of the passive investor’s interest in the deal.

The governing LLC agreement contained ordinary language allowing each party to pursue “other business interests [] and investments, some of which may be in conflict or competition with the business of the Company.” The agreement also declared: “pursuit of such activities . . . shall not be deemed wrongful or improper.”

The passive investor argued that this language only allowed the sponsor to unilaterally invest in other real property, but didn’t apply if an opportunity arose to buy out other investors in this particular property. The court disagreed. It found this language was broad enough to immunize the sponsor from any claims for having unilaterally exploited the business opportunity that arose when the first-priority investor wanted out of the deal.

The agreement also contained typical language requiring the sponsor to “discharge its duties in a good and proper manner . . . as would a prudent manager under similar circumstances,” taking into account the interests of the members, which would include the residual passive investor. The residual passive investor argued that this language required the sponsor to share the buyout opportunity with the passive investors. The court again disagreed, deciding that the quoted language just didn’t get there, especially given the sponsor’s very broad rights to conduct whatever other business it wanted.

The sponsor did not do so well on the second issue. There, the court concluded that the sponsor’s unilateral increase of the preferred return from 9% to 12.5% might very well have violated the sponsor’s fiduciary obligations to the residual passive investor. Although the sponsor had wide authority to manage the LLC’s affairs and make certain amendments to the LLC agreement, that probably did not allow the sponsor to unilaterally amend the economic terms in a way that hurt the residual passive investor. So the court allowed the litigation to continue on that particular issue.

The case shows that Delaware courts will not go out of their way to allow passive investor members to assert claims against sponsors, at least where the language of the agreement doesn’t unambiguously support a claim. The courts will enforce broad-brush language that exempts sponsors from liability, and won’t go out of their way to help a disgruntled investor.

On the other hand, if a sponsor takes direct action that economically hurts a passive investor, the court might very well draw the line and allow the residual passive investor to assert a claim.