In the first in a series of blog posts examining candidates’ housing policies, Redfin chief economist Daryl Fairweather breaks down rent relief, put forward by both Kamala Harris and Cory Booker

What is rent relief?

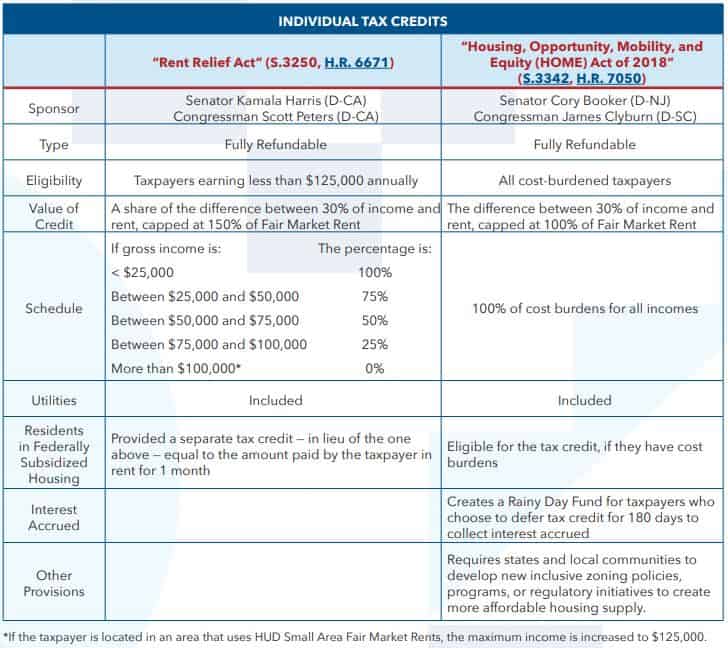

Two of the latest Democrats to announce they are running for president have advocated for rent relief. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker have both introduced rent relief legislation to provide a refundable tax credit to renters spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities. In effect, rent relief is a redistribution of income to families who have low incomes relative to their cost of renting. Booker’s legislation has a provision on changing zoning laws and regulations to increase the supply of housing, but rent relief on its own is a way to give money to families whose cost of renting exceeds their ability to pay. The size of the rent relief credit depends on household size and income and the Harris and Booker proposals have different formulas:

Source: National Low Income Housing Coalition

About half of all Americans are rent-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent. Families burdened by rent have little money to put towards savings, and one medical bill, speeding ticket, or unforeseen emergency expense could result in a missed rent payment, which increases an already vulnerable family’s risk of eviction or even homelessness. So rent relief could be an effective policy for preventing homelessness.

Has rent relief been attempted before?

The section 8 housing voucher program already provides rental assistance to families burdened by rent. Cities and counties administer the vouchers and set their own rules for eligibility. For example in Seattle, in order to be eligible the renter must make less than 50 percent of median income in Seattle and the rental unit must have a “reasonable” price. The housing voucher program hasn’t been an obvious success. The evidence is mixed on whether housing vouchers improve the housing outcomes of recipients, and researchers have found that landlords discriminate against housing choice voucher recipients. In many cities, there aren’t enough vouchers for everyone who would qualify, leading to years-long waiting lists. Giving rent-burdened families cash through a tax credit instead of a voucher could at least solve the problem of landlord discrimination and ensure all eligible renters could take advantage of the benefit.

What are the unintended consequences of rent relief?

One issue with rent relief is that it’s only available to families who pay high rents and isn’t available to homeowners. Therefore this policy encourages families to rent instead of buy, and is a sort of resignation to a future where fewer and fewer Americans gain wealth and connection to their communities through homeownership. While the government subsidizes homeownership in other ways, rent relief encourages renters to stay renters, and solidifies the divide between the renting class and the property-owning class.

Critics of rent relief in its current form would also argue that a family receiving rent relief could be incented to spend more on rent or utilities because it would mean a larger tax credit. For example, if a family were deciding between a rental with in-unit laundry versus a rental with communal on-site laundry, they might decide to pay more for in-unit laundry if they knew they would receive the difference in rent back through rent relief, even though that amenity isn’t essential. Also, environmentalists might not like that utility costs are part of the rent relief calculation. A family might be more likely to take long showers or crank the air conditioning in the summer if they know the cost of water and electricity will be paid back as rent relief.

How could this policy be improved?

Instead of tying rent relief to a family’s personal rent burden, relief could be tied to local housing prices and become available to low-income homeowners as well as renters. This way, the assistance would become more available to low-income families in expensive cities, which would otherwise be unaffordable to them. Enabling more low-income families to live in cities can give them easier access to job opportunities and amenities that can help them to earn more money and give them more freedom about where and how to live, whether that’s becoming a homeowner or moving closer to public transit. If more low-income families could afford to live in cities, it would also help cut down on socio-economic and racial segregation that has risen with urban home prices.

This post first appeared on Redfin.com. To see the original, click here.