GOLETA, Calif. —

Seven days a week, dozens of retirees, college students, children and working parents flock to a sunbaked patch of pavement in this oceanside city just west of Santa Barbara. They’re here to play pickleball, a nearly 60-year-old sport that’s seen a surge in interest during the pandemic, wreaking genteel havoc from coast to coast.

On Feb. 18, as the waning winter sunlight filtered through the surrounding chain-link fence, Mike Myers dominated most of the competition. A dedicated player and leading local advocate for the sport, the 56-year-old holds court here at the Goleta Valley Community Center, smacking balls away with boastful shouts tempered by words of encouragement and advice.

“Right on the line!” he exclaimed, gesticulating across the court with his paddle after executing a particularly skillful forehand. “Nice try,” he said after another. “No way you were getting that one.”

Steve Lough, left, and Kathi Scarminach go after a ball while playing a game of pickleball at the Goleta Valley Community Center.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

His opponent, a 23-year-old college exchange student from Bavaria named Max Krautter, responded later in the game with a brief education in the fluid use of German expletives.

A democratizing sport with a low barrier to entry, anyone can quickly pick up pickleball without spending much money or taking years of lessons. The rules are relatively easy to learn, and the basic strokes are simple enough to get down during a couple of friendly games.

Because the playing surface is about one-fourth the size of a tennis court, there’s little ground to cover, especially in doubles. The sport is so physically forgiving that it’s unremarkable to see a gray-haired pair put a beating on their teenage grandkids.

But the rapid rise of the game — and the decibel levels, crowds and vocal advocacy it generates — has precipitated an intense backlash in communities across the country.

A pickleball enthusiast’s car at the Goleta Valley Community Center.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

In a lawsuit against Newport Beach, a Corona del Mar woman claimed the sounds of people playing pickleball 100 yards from her home caused her “severe mental suffering, frustration and anxiety.” A South Carolina couple filed suit against a country club near their home, alleging that late-night pickleball games caused “unreasonable interference with” their “enjoyment of their property.” In dozens of legal proceedings, people have successfully claimed that allowing pickleball violates local municipal codes or homeowners’ or condominium associations’ rules.

In New Jersey, a local blogger wrote last year that a village with about 25,000 residents had “declare[d] war on pickleball.” Earlier this month, a local news outlet published nearly 4,000 words about a months-long showdown over the sport on a sparsely populated British Columbian island in an article titled “The pickleball coup.”

“We hear the ball hit the paddle from inside our homes all day long, 8 a.m. to 8:30 p.m. I want to stress that it’s all day, nonstop.”

Katie Pazan, resident of a luxury townhome community within earshot of the Goleta Valley Community Center.

Some of the language used to describe the internecine pickleball debate is extreme, but it matches the tenor of the confrontations, which often turn neighbors against one another.

Goleta, best known as the home of the UC Santa Barbara campus, has been embroiled for months in one such battle, over the future of pickleball on a 27-year-old tennis court at the Goleta Valley Community Center in the city’s old town district.

Last year, the center asked the City Council to greenlight a plan to permanently convert the tennis court into four pickleball courts, resurface and paint the playing surface, install fixed net posts, and replace damaged fencing. The outdoor facility is owned by the city, but the nonprofit center has leased it for years and said it would pay for the upgrades.

During several hours of public meetings beginning in November, local officials read and heard testimonials from hundreds of pickleball fans who support the project and a handful of nearby residents who consider it a nuisance. The final meeting on the topic — at least for now — unfolded Tuesday evening.

Mike Myers, left, prepares to return a volley against Max Krautter while playing a game of pickleball at the Goleta Valley Community Center. Judy Lough, right, heads to her position.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

*****

There’s no question that pickleball is noisy.

Researchers have shown that the sound of a solid pickleball paddle hitting one of the sport’s hard plastic wiffleball-like balls can be more than 25 decibels louder than that of even the hardest-swung Wilson connecting with a felt-covered tennis ball.

Katie Pazan lives in a luxury townhome complex within earshot of the Goleta Valley Community Center. During a virtual City Council meeting in January, she decried the “nuisance” sounds of people playing pickleball on the community center’s courts.

“We hear the ball hit the paddle from inside our homes all day long, 8 a.m. to 8:30 p.m.,” she said. “I want to stress that it’s all day, nonstop.”

Judy Lough, left, and Kathi Scarminach play a game of pickleball at the Goleta Valley Community Center in Goleta.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Myers, the pickleball enthusiast, dismissed those concerns, claiming the sound of the play drops to a minimally bothersome level by the time it reaches nearby homes.

Tim Hayes, a 65-year-old engineer who says he lost 35 pounds playing pickleball regularly, acknowledged that “the sound aspect is real” in an interview after coming off the community center courts on Feb. 18. He said a neighbor has a pickleball court about 200 yards from his Goleta house, and that he can often clearly hear the game being played.

“I don’t mind because I just love the sound of it. I’m jealous that someone’s got it in their backyard,” he said.

And yet, like more than 300 other pickleball players in this town of about 30,000 people, Hayes strongly supports the court revitalization plan and cast doubt on claims that pickleball noise bothers nearby residents.

“You’ve got to be kidding. We’ve got the airport, Highway 217, the bus depot and the 101,” he said. “This has got to be the noisiest place in Santa Barbara County, and somebody complained about the noise?”

A sign at the Goleta Valley Community Center says “Join the fun. ALL are welcome!” in Spanish.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

And so a line was drawn in the grass between two groups of residents in this little corner of Goleta. The same thing has happened in communities across the country as the sport has moved into new towns and suburbs accustomed — and in many cases entitled under the law — to hearing less of a racket.

Over the last two years, Nicholas Caplin, a founding partner at Lubin Pham & Caplin in Irvine, has represented members of more than 10 California residential communities with newly built or converted pickleball courts in claims against the homeowners’ associations that allowed the changes.

Caplin said he could not discuss the specifics of the cases because they all settled via mediation and are typically subject to confidentiality or non-disclosure agreements. But he said that in case after case, HOA codes and covenants included noise provisions that the pickleball courts were ultimately found to have violated.

Lisa Streett goes after a ball while playing a game of pickleball at the Goleta Valley Community Center.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“Homeowners’ associations say, ‘Let’s do a nice thing and make tennis courts into pickleball courts.’ The outcome of that is additional noise,” he said. “The HOA is convinced of their exposure and takes action to avoid escalation, usually by settling, by either agreeing to no pickleball or drastically reducing noise associated with pickleball.”

Legal claims against municipalities in California and across the country have forced similar resolutions, because volume levels associated with pickleball violate noise restriction ordinances for residential areas. The claims often result in “really ugly neighborhood drama,” Caplin said, but people who live near the courts typically win out.

*****

To substantiate claims of excess volume from pickleball courts, Caplin and other attorneys sometimes turn to companies like Spendiarian & Willis Acoustics & Noise Control.

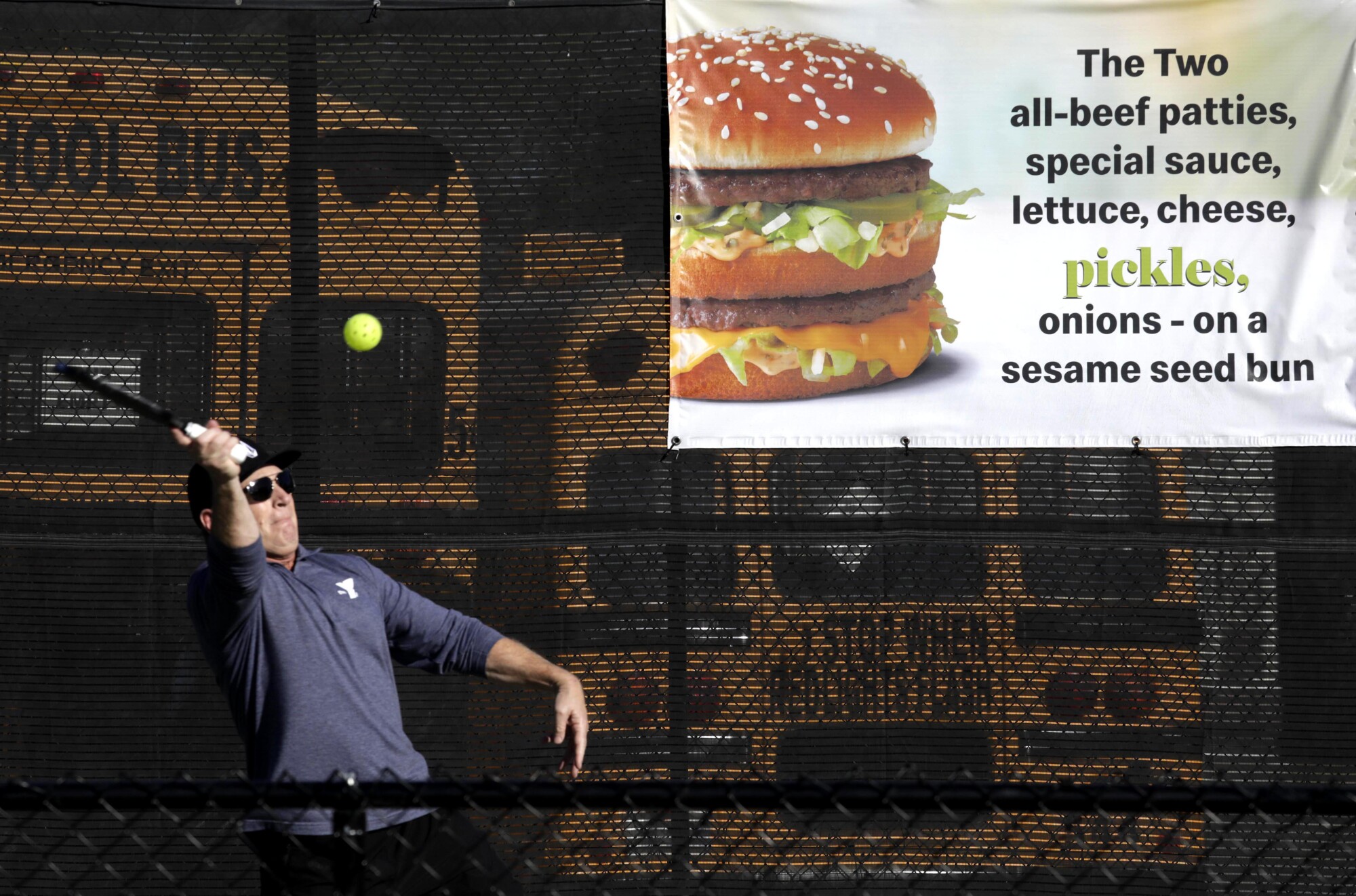

Walt Bies goes after a ball next to a sign that highlights the word “pickles” during a game of pickleball at the Goleta Valley Community Center.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

For about a decade, Lance Willis, principal acoustical engineer at the Tuscon-based firm, has performed pickleball-related acoustical analysis in communities from Palm Springs to Massachusetts to Canada.

Often, he is hired to measure the sound levels emanating from pickleball courts so the results can be compared against volume thresholds outlined in municipal codes or HOA rules.

Sometimes that requires him to set up his handheld NTI Audio XL2 audio and acoustic analyzer on a tripod at multiple points on or near a court during play to determine how loud it is. Or Willis will set the device up on the property line of an adjacent home to measure how much noise is actually reaching neighbors.

The loudest sound produced hundreds of times during a pickleball match — the two-to-four-millisecond “impulse sound” generated when a paddle connects with a ball — is inherently louder than those of sports like tennis or basketball, he said.

While researchers have found that even a “loud” tennis shot will usually fall short of 60 decibels, Willis said he’s recorded peaks of 85 decibels from a backyard more than 50 feet away from a pickleball court.

Lisa Streett, left, Lori Rozenburg, Sharol Janes and Lori Brakka show off their paddles while taking a break from playing pickleball at the Goleta Valley Community Center.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Extended exposure to 80-decibel noise can cause hearing damage; it’s equivalent to hearing a freight train from just under 50 feet away, according to a Purdue University study. The sound of a blender comes in at 88 decibels.

“Pickleball may not appear to produce high levels of acoustical energy, but it does,” he said. “It is not equivalent to tennis or basketball or a lot of the other common activities that you hear at parks. It really has a higher noise impact.”

That higher noise impact can mean the difference between violating rules and regulations, as evidenced by numerous places where tennis has been deemed permissible without sound mitigation but pickleball has not. It can also have negative consequences for nearby residents, according to Tom Spendiarian, principal architect at Spendiarian & Willis.

“One guy was a Vietnam vet, an old guy, and he said it sounds like a mortar being dropped in a mortar tube — the plunk sound” of a paddle and pickleball colliding, Spendiarian said. “It freaks him out.”

Steve Lough and his wife, Judy, tap paddles at the end of a pickleball game at the Goleta Valley Community Center.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

*****

By the time the lights over the Goleta Valley Community Center’s four pickleball courts came on one recent Friday evening, dozens of games had already been played. Unlike tennis, in which a single match between two good players can tie up a court for hours, many pickleball matches last just 15 to 30 minutes.

The sport is perfectly suited for high-turnover open play. Multiple times an hour, a fresh crop of players steps out on the courts, gets their blood pumping, then steps back outside the fence.

Some pickleball players scoff at concerns about noise and commotion and emphasize the sport’s benefits.

“There’s just people out there that are just cranky,” Lori Brakka, a 59-year-old Goleta grandmother, said after finishing a match at the community center that Friday afternoon. “They don’t enjoy hearing people laughing and having a good time.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

JoAnne Plummer, parks and recreation manager for Goleta, highlighted pickleball’s good side.

“From a recreational standpoint, the passion for pickleball and the need is nice to see. It’s nice to see people passionate, being outdoors and doing something social,” she said last month.

But she acknowledged the concerns about the noise, and about whether the community center’s plan to permanently install pickleball courts — and charge usage fees — would shut out lower-income residents and people of color.

Plus, some athletes in Goleta and beyond believe that permanently converting courts for pickleball unfairly reduces the number of locations where people can play tennis or other sports.

*****

Pickleball is undergoing a major surge in popularity. According to USA Pickleball, about 4.8 million people played the sport at least once in the U.S. in 2020, an increase of nearly 40% in just two years.

But tennis remains far more popular, with tournaments around the world, four of the most-watched global sporting events and more than 21 million people playing the sport in the U.S. in 2020, according to a 2021 study by the Physical Activity Council. That’s a 22% increase of total players in 2020, nearly 3 million of whom played tennis for the first time that year.

Fans frequently call pickleball “America’s fastest-growing sport.” But while the data show the pandemic has driven large numbers of people to the courts, they don’t say whether they’re swinging pickleball paddles or tennis racquets.

At Goleta’s January City Council meeting, Mayor Pro Tem Stuart Kasdin pushed back against a claim by local pickleball advocate Chuck Riharb that “trends” show “tennis people are moving to pickleball” locally and nationally.

“The assertion that people aren’t playing tennis anymore, that it’s just a dying sport or something like that, I think is unfounded,” Kasdin said. “People are playing tennis.”

But they’re also playing pickleball.

And now Goleta has four more courts permanently dedicated to the sport. On Tuesday, the city’s council unanimously approved the Goleta Valley Community Center’s court revitalization proposal.

First, the center had to agree to take steps to address neighbors’ concerns, including adding sections of windscreen and wooden fencing to dampen sound, offering free monthly pickleball workshops and eliminating most usage fees.

“We listened, they listened, and they came up with a compromise I can live with,” Mayor Paula Perotte said at the council meeting Tuesday evening.

“We have some pickleball advocates very happy tonight.”