When the Los Angeles Times opened its Orange County offices in 1968, the event was so low-key that it didn’t generate coverage in the pages of the paper itself. The office and printing plant, however, did materialize in the classified ads, where The Times advertised part-time jobs — “Call Now!” — whose responsibilities were left mysteriously undescribed.

To be certain, the complex, located on Sunflower Avenue, north of the 405 Freeway and west of South Coast Plaza, wasn’t exactly headline-making news. Designed by William L. Pereira & Associates — the Los Angeles-based architectural firm that produced the original (now-demolished) campus for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and was then hard at work on a master plan for the city of Irvine — the paper’s Costa Mesa office was a boxy newsroom building linked to an industrial printing plant by a simple, covered breezeway. Nothing on the scale of paper’s grand Streamline Moderne headquarters from the 1930s in downtown L.A.

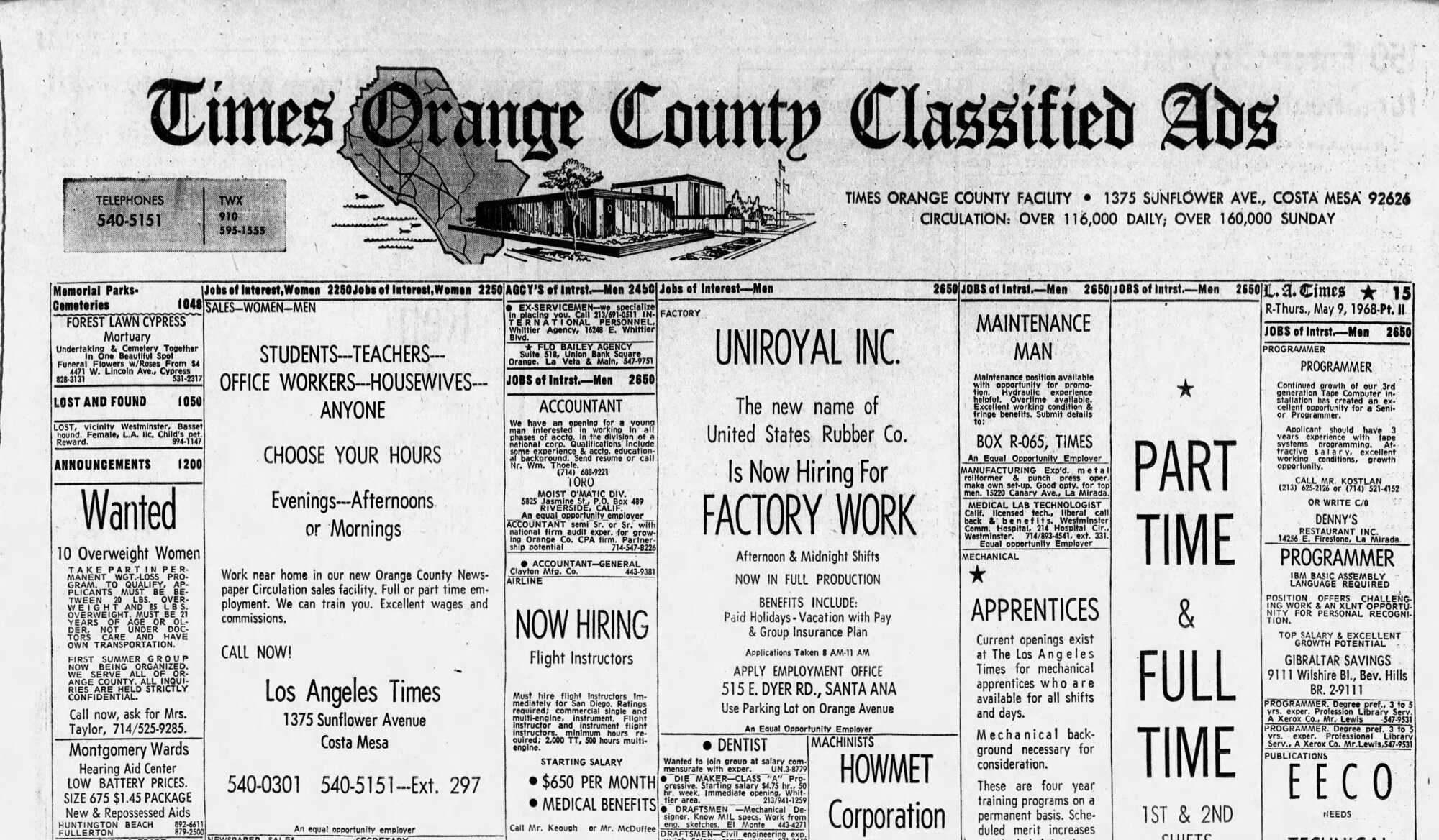

Even so, The Times used an illustration of the Pereira complex on the masthead of its classified ads section in Orange County.

The Times’ Orange County Classified Ads section from 1968 featured an illustration the paper’s Costa Mesa headquarters, designed by William Pereira & Associates.

(Los Angeles Times)

Now The Times’ old Orange County headquarters has found new life thanks to Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects, the Los Angeles-based firm behind the Culver Steps, which helped turn a bleak Culver City parking lot at a traffic-choked intersection into an interesting sequence of public plazas and commercial spaces. Led by partner Patricia Rhee and associate George Racomura, the renovation has successfully turned the dour-looking Times complex into an office campus for the 21st century.

It was quite the job. By the time the property was sold to private developer SteelWave LLC in 2017, it had been subjected to numerous industrial-scale additions. The ungainly, 400,000 square-foot mass of interconnected structures seemed to have swallowed Pereira’s original design whole. In response, EYRC architects pulled out the scalpels and began slicing open ceiling and walls to produce skylights and windows. A dramatic open-air atrium at the heart of the complex — capped by a remnant of old Los Angeles Times signage — marks the site where Pereira’s breezeway once stood.

In addition to a new look and a new name, the complex now known as the Press also has a new tenant: Anduril, a defense contractor that designs drones. It’s a symbolic inversion of architectural purpose: a building once inhabited by a newsroom, an institution that is purportedly about putting an uncomfortable spotlight on the inner workings of power, will now be employed for the purpose of fabricating military technology — power in its most brutish form.

A view of the open-air atrium at the Press, the office campus that now occupies The Times’ old Orange County newsroom and printing plant in Costa Mesa.

(Matthew Millman / Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects)

Ultimately, it brings The Times’ story full circle. For much of its life, the paper was headquartered in a purpose-built structure — really, a series of structures — in L.A.’s Civic Center, whose surface ornamentation paid tribute to, among other figures, the inventor of the printing press, Johannes Gutenberg. In 2018, The Times relocated to El Segundo, inhabiting a blank, Modernist structure whose previous occupants included Hughes Space and Raytheon.

Certainly, in Southern California, where aerospace and defense have long been embedded in the economic, political and cultural landscape, there is a great deal of overlap between the military-industrial complex and — well, everything else.

Pereira designed buildings for a number of defense companies, including Beckman Instruments, Ford’s Aeronutronic Systems and North American Rockwell — the last, an absurdly monumental ziggurat in Laguna Niguel that, for whatever reason, is now painted an unsympathetic shade of yellow. In the 1980s, a representative from the aerospace firm Rohr Corp. sat on the board of directors of the Times Mirror Co., then The Times’ parent company. (The Times is now privately owned by the Soon-Shiong family.)

Historic entanglements with the defense industry aside, Times photographer Allen J. Schaben and I will likely be some of the last Times journalists to wander freely in the paper’s old O.C. building for a very long time.

A view of The Times’ Orange County buildings as designed by William L. Pereira & Associates and photographed by Julius Shulman in 1968.

(Julius Shulman / Getty Research Institute / J. Paul Getty Trust)

Another image taken by Julius Shulman of The Times’ Orange County building shows the breezeway between the offices and the printing plant.

(Julius Shulman / Getty Research Institute / J. Paul Getty Trust)

To be clear, Rhee and Racomura never intended to design a suite of spaces for a defense contractor. After The Times complex was acquired by the developer in 2017, the intention was that the Press would be renovated as a mixed-use development with offices, retail and a food hall. And that is exactly what EYRC designed.

But last year, at a point at which renovations were nearing the finish line, the developer leased the entire building to Anduril — and then some. The company, which designs drones for military uses and for the “virtual” wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, has, as of late, been the recipient of much federal government largesse. Its needs were so great that it added a tilt-up concrete structure that functions as additional office space. (That building was already in use when I visited, so I was unable to enter. My tour, which took place in February, was confined to the old Times spaces — all of which were awaiting an interior buildout, to be completed by a different firm.)

Regardless of who is now in the building, the residue of The Times’ history as a chronicler and shaper of Southern California remains embedded in the structure thanks to a series of thoughtful design moves by Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney.

If the building had, over time, become a bit of an architectural pile-on — extensive additions were made in the ’70s and ’80s that completely changed the original building’s dimensions and scale — Rhee and her team set about clarifying some of the jumble.

“We called it selective subtraction,” says Rhee of how the team approached the renovation. “We’re trying to make this massive industrial, inhospitable place into this desirable place — not for machines, but for humans. We were trying to bring in natural light and air and human scale to the building.”

Patricia Rhee and George Racomura, of Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects, stand in the atrium at the Press.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

I saw The Times O.C. complex, briefly, in 1991, when I had to go there to take a drug test for a summer job in Los Angeles while I was in college. My memories are of a distinctly uncharismatic, warehouse-y building bathed in pallid fluorescent light. (Before the advent of digital media, newspaper offices — with their attendant printing plants — looked, felt and smelled industrial.)

EYRC began by clearing some of what had been added over the years, in particular, at the center of the rectangular complex, where Pereira’s breezeway had once been located. They cut swathes of 1970s additions back to the steel frame to create an entrance via an open-air three-story atrium studded with plants. In the levels above, pieces of cantilevered floor plate jut into the space, creating cinematic balconies. An exterior stairway dressed in weathered steel adds to the industrial vibe and supplies additional viewpoints. It would have been an ideal site for influencer-watching had the building been used for its intended purpose.

The architects made similar cuts to the southern end of the building, adding skylights and taking away concrete panels to reveal part of the building’s armature, an X-shaped frame made of steel, making for a remarkable portal into the structure. Here, the outdoor areas feature seating areas and a small pavilion.

It has made the glum newspaper architecture into something inviting.

“We didn’t do a lot of crazy intervention or add-ons,” Racomura says. “The building’s form is driven by function and by peeling away panels so you could see the bones behind it.”

A view of the southern entrance of the Press shows the ways in which the architects have revealed aspects of the building’s structure.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Elsewhere, EYRC has tried to let the building retain an imprint of the life that came before.

Weathered walls and beams, intentionally left unpainted, reveal the building’s industrial history. A metallic yellow staircase that once led from the dock to a catwalk overlooking the presses remains largely untouched. On the eastern side of the building, on what was once a very long dock, visual evidence remains of the rails that once supported the conveyer belt that moved bundles of newspapers to waiting delivery trucks. Indeed, it not only remains — the architects framed it with a rock garden.

Overhead, EYRC cut skylights into the cantilevered canopies that protected the dock, allowing light to penetrate the concrete — and, in some ways, pay tribute to aspects of Pereira’s breezeway design. To soften textures, pieces of the dock, as well as areas below it, have been carved out to make way for plantings, turning the structure into a linear garden. It’s another place to hang out. It also functions as an alternate circulation route, allowing someone to traverse the length of the building outdoors rather than within, with various points of entry and exit along the way.

It’s a smart piece of indoor-outdoor design. Whether Anduril will maintain that porosity remains to be seen. (I’m not holding my breath.)

A metallic staircase remains from the Press’s days as printing plant. To the right, a series of pavers mark the path of a conveyor belt that took bundles of papers to waiting trucks.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

This building marks an interesting chapter in Southern California history — serving as evidence of the ambitions of Otis Chandler, the youthful and unlikely heir to the Chandler family business, the Los Angeles Times. The paper, for much of its existence, had functioned as journalistic laughingstock; Otis helped transform it into a Pulitzer Prize-winning media organization with bureaus around the world.

The establishment of the Orange County edition represented his interest in expanding The Times’ geographic reach — and served as the first satellite plant for any metropolitan daily in the country. At its peak, the plant had about 1,000 employees and printed a quarter of a million newspapers daily. All of those defense workers who lived in Irvine, Fullerton, Anaheim and Huntington Beach? They needed a newspaper to read. Pereira, in the meantime, went on to design the corporate headquarters of the Times Mirror Co. in downtown L.A. in the 1970s.

But a general decline in newspaper readership and the recession of the 1990s, followed by a three-ring circus of corporate leadership at The Times, would be the undoing of the paper’s Orange County edition. In 2000, Chicago-based Tribune Media Co. took over as The Times’ new parent company. By 2014, the Costa Mesa building had been shut down, its presses dismantled. In 2017, the property was sold to SteelWave for $65 million.

Now the space will be employed to design drones for the border.

Ironically, through EYRC’s thoughtful renovation, The Times’ buildings physically embody the sorts of virtues to which media organizations often hold themselves up — ideals like openness, transparency and connectivity.

Too bad there will be few people who ever get to see them.

A view of the loading dock area, converted into a linear garden that hugs the eastern flank of the old Times Orange County building.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)