It’s been a dizzying few months for the news cycle.

President Joe Biden is officially in. Hedge funds are bleeding thanks to a Reddit sub-group (what is that?) while a global pandemic still rages. Tom Brady, at age 43, is about to play in his 10th Super Bowl in twenty years.

Meanwhile, thirty minutes north of downtown Miami, a Florida real estate family that’s been called the ”other Trumps” for decades has been too busy building their next billion-dollar masterpiece to pay attention to the outside noise.

The beachfront lawn at Acqualina Resort & Residences in Sunny Isles, Florida is one of many reasons … [+]

Courtesy of Acqualina Resort & Residences

Few people have more experience in the ultra-high net worth real estate space than South-African born businessman Jules Trump. Along with his younger brother and lifelong business partner, Eddie, Jules is co-chairman of The Trump Group, which over the past four decades has assembled a sprawling entrepreneurial empire from real estate and hotels in Florida and California to technology start-ups in Tel Aviv.

“No relation to the President or the Trump Organization,” Jules prefaces almost instinctively when I meet him. “We both build some pretty nice real estate, so it’s easy to get us confused. I just don’t put my name on my buildings . . . Plus my buildings are nicer.” Wink. Wry smile.

MORE FOR YOU

The signature “Acqualina” red umbrellas, perfectly manicured lawns, and aquamarine Atlantic Ocean … [+]

Courtesy of Troy Campbell/Acqualina Resort & Residences

It’s 94 degrees and 85% humidity when Jules first agrees to sit down with me and my wife over Labor Day weekend last year. At the time, COVID-19 is still raging across South Florida. ICU beds in Miami are maxed and hundreds of patients on ventilators are dying every day. Jules is 77. His wife of 50 years, Stephanie, is 74.

But under the socially distanced shade of his perfectly shucked palm trees, against the backdrop of his surgically Masters’ manicured lawn, just off the radiant white beach flanked by the aquamarine Atlantic and the signature flaming red umbrellas of his Acqualina Resort & Residences, the madness of the world and the risk of the pandemic couldn’t feel farther away.

Jules and his wife Stephanie have been married for 50 years and now have 13 grandchildren

Courtesy of Nick Garcia/Acqualina Resort & Residences

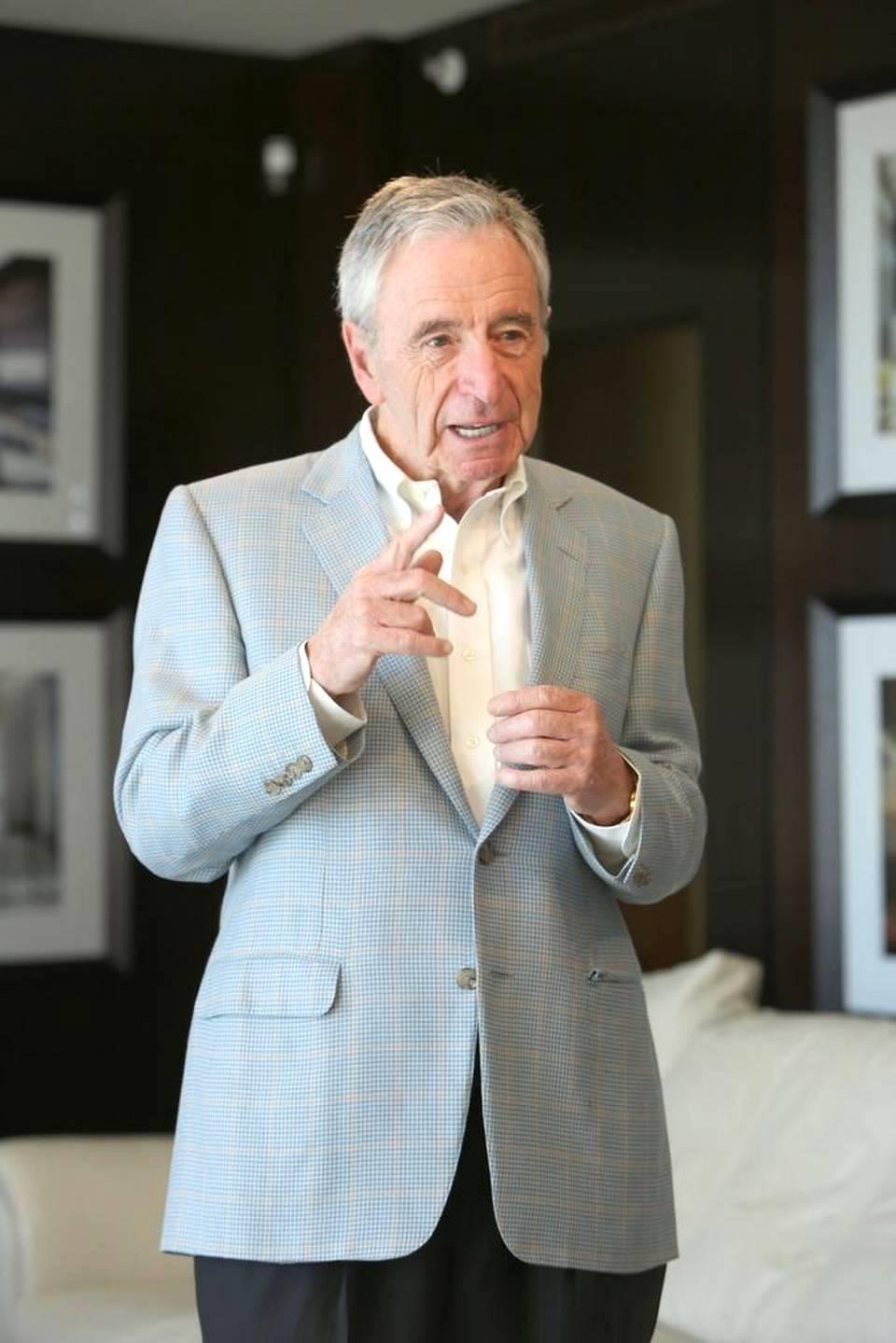

Jules is dressed in a loose fitting Acqualina dress shirt, pressed tan khakis, and loafers when he walks up to greet my wife and me. His silver peppered hair is already tasseled from the onshore breeze and the deep lines in his tanned face suggest a life that’s been lived to the fullest with a nearly constant stream of things to smile about.

Last year pre-pandemic, you’d be more likely to see Jules around Acqualina in a well-trimmed, Madras patterned sport coat and a perfectly tensioned tie, hustling to his next development meeting after hobnobbing with residents and guests. But these days, he’s given in to wall-to-wall Zoom calls, working from home, and, as he puts it, rediscovering his “casual side”, while his wife Stephanie has been finding her inner Cordon Bleu chef largely in isolation since COVID-19 shut the world down.

Jules and Eddie Trump’s new Estates At Acqualina development in Sunny Isles, Florida is raising the … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

Between the masks, the wind, and his still thick South African accent, I can barely discern what Jules is saying as we greet each other. Yet, there’s something that preternaturally beams from him—like being in the presence of a recently retired golfer who’s just coming off winning the last of a dozen PGA majors over a storied career.

Unlike a lot of celebrity South Florida developers, Jules is notoriously adept at steering clear of the press, as well as panel discussions, charity parties, and real estate events that force him to talk about himself because narcissism isn’t his style.

At the frequently self-serving upper edges of luxury real estate where he’s resided for more than three decades, it’s Jules’ contrarian humility and genuine kindness that are far more legendary. As soon as you spend five minutes with him, it’s obvious that he’s much less interested in talking about himself, his projects, or the dozen Rolls Royces valeted in front of his hotel than he is about his true passion in life—people.

Jules Trump (R) with his younger brother and lifelong business partner Eddie Trump (L)

Courtesy of Acqualina Resort & Residences

Jules (along with his brother Eddie) wasn’t born into a real estate or hospitality empire like a lot of other successful development scions.

His parents owned a modest clothing store in Johannesburg before his family immigrated to America (at one point employing Winnie Mandela, Nelson Mandela’s eventual wife). When he was twelve, Jules started folding shirts, greeting customers, and chatting them up. That’s where his first found his instincts for exceptional customer service.

“My parent’s store was where it all started,” recalls Jules. “It doesn’t matter what you’re selling—a hat, windshield wipers, or a $40 million penthouse. If you don’t make people feel special, they always have somewhere else that they can go. But putting people first will always bring them back.”

That customer-first approach and atomic-level attention to detail has quietly made Jules and Eddie two of the most successful, under-the-radar developers and entrepreneurs in America no one knows about. Which is exactly the way they’ve liked to keep it for the past forty years.

Jules Trump (“No relation to the former President”) started his career folding shirts and chatting … [+]

Courtesy of Acqualina Resort & Residences

Jules and his family left South Africa when he was 29. Though the global disinvestment campaign that would eventually cripple the country’s economy was still years away, South Africa’s racially segregated Apartheid system was morally unconscionable to Jules, Eddie, and their parents. So like tens of thousands of other native-born Afrikaners, they took their talents and futures elsewhere.

“Coming from South Africa in the 70s, America was the golden land of opportunity,” says Jules of his family’s decision to come here. “America was free and open. There was this feeling that anyone could do anything if you worked hard enough at it. It was the idea about America that I loved. I still love it.”

The valet at Acqualina Resort & Residences. Customer service and treating everyone with respect the … [+]

Courtesy of Acqualina Resort & Residences

Jules and Eddie got their entrepreneurial start in New York City buying a struggling men’s fashion retailer called Bond Clothiers that sold “double pant” suits (two pants included with every jacket) out of prime Manhattan real estate in Times Square and on Fifth Avenue.

Bond, the brothers reckoned, didn’t have a product or manufacturing problem. It had a customer service problem—which as a practical and financial matter was far easier and less expensive to solve.

“Treating everyone with respect is the most basic foundation of every business,” Jules responds when I ask him about the calculus behind buying Bond. “And that’s been the approach to everything that Eddie and I have done in business ever since. It all comes down to the same, simple principle: if customers aren’t raving fans then there’s only so much that you can do cooking the numbers.”

Over the next decade from 1974 to 1985—while The Donald was building his first namesake Fifth Avenue Manhattan skyscraper—the “other Trumps” were quietly selling hundreds of thousands of double pant suits to the city’s burgeoning financial commuter class as fast as they could stitch them. They subsequently grew the company to more than 150 locations nationwide, all while simultaneously amassing a not-so-small retail real estate empire.

Economists call this owning the cows while selling the milk. But Jules and Eddie instinctively knew that what they were doing was just good common sense. They eventually sold off Bond in pieces as the company’s valuation soared and became bonafide, first-generation American immigrant success stories by the time they were 40.

“But Bond was just the launching pad,” adds Jules, smiling wryly again. “Eddie and I were just getting started.”

Location, location, location. Jules and Eddie Trump have been pioneers in South Florida as luxury … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

The Trump brothers’ first entrée into proper real estate development began in 1980, when Jules and Stephanie took their three young children on vacation from New York City to Miami for the first time.

It was mostly a pleasure trip, Jules recalls. But he’d already had his eye on the weather, beaches, and cheap waterfront land north of the city where a large diaspora of Jewish immigrants from around the world had begun to transform the previously rundown stretch between Route 1 and A1A that’s now Aventura and Sunny Isles into something more purposeful.

“Back then this place (Aventura and Sunny Isles) was like a junkyard,” Jules remembers, “It was this chaotic mess of swampland, time shares, industrial properties, and cheap, run-down motels. People from outside Miami didn’t know how amazing the beaches were here yet. No one from New York would stay south of Palm Beach. But Eddie and I immediately saw potential where others saw problems. It was just a matter of making something out of nothing.”

Jules’ and Eddie’s first “something” was an 84-acre mosquito-infested peninsula of tangled mangroves for sale a mile inland from the beach called Williams Island—just south of what is now North Miami’s ultra-exclusive Aventura neighborhood. To this day, it’s still the most impulsive business decision that the brothers have ever made in their lives.

“Eddie and I closed on the property 9 days later,” recalls Jules. “It was the fastest business deal we’d ever done. But Eddie and I knew what Williams Island could become. Everyone else thought we were crazy.”

By 1985, the island’s swamps and mosquitos were mostly gone and the first of what would eventually become eight high-rise towers was coming out of the ground.

“What we did at Williams Island was one of the first lifestyle developments of its kind in South Florida,” says Jules of that period (he and Eddie were both still in their early 40s at the time). “It was a massive gamble. So many things could have wrong. But we knew that if we focused on creating an amazing living experience that people couldn’t find anywhere else, the buyers were out there.”

Creating a lifestyle experience with the highest level of architectural and service standards has … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

The essence of that “other Trump” experience, says Jules, wasn’t gold-plated fixtures, overstuffed furniture, and the family surname in lights. It would be rooted in something far more enriching and magnetic—people. Long before the age of Instagram influencers, it was a stroke of marketing brilliance.

Jules’ and Eddie’s first “brand ambassador” for Williams Island was the Italian actress and model Sophia Loren, who at the time was one of the most fashionable and recognizable faces in entertainment. After they finished the first phase of the clubhouse and amenities, the Trump brothers called her cold and eventually convinced her to move to Williams Island to become its first official spokesperson.

Retired Australian tennis legend Roy Emerson was next—who was then the winningest men’s Grand Slam champion in history. Eddie lured Emerson to run the club’s tennis program, which eventually attracted other stars and Grand Slam champions like Bjorn Borg and Chris Everett, both of whom wintered at Williams Island between major tournaments.

Jules and Eddie also shrewdly re-branded the “junkyard” that was formerly Aventura and Sunny Isles into the “Florida Riviera” and built national and international marketing campaigns around it to attract foreign buyers. It was a crafty sleight of phrase that over the next two decades would help turn Aventura and Sunny Isles into one of the most coveted stretches of coastal real estate on America’s eastern seaboard.

By 1990, Williams Island’s brand momentum had become unstoppable. Today, it encompasses more than 2,000 luxury residences in addition to a Mediterranean-styled village with shops and restaurants as well as resort amenities and a yacht club that would rival anything in the Hamptons—or the actual French Riviera.

When Jules and Eddie Trump arrived in Sunny Isles, Florida all they saw was potential where other … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

Buoyed by Williams Island’s success, Jules moved his family to South Florida full-time the following year, while he and Eddie—now legitimate luxury real estate developers with the gravitas to prove it—turned their attention to Sunny Isles to the east next door.

At the time, the nearly-mile long stretch of Atlantic beachfront consisted mostly of rundown motels, time shares, and liquor stores fractured across complicated property lines that had failed to attract any significant developer interest for years. Consolidating the land needed to make a new luxury, high rise development that would attract UHNW foreign buyers financially viable would be onerously time-consuming, most of them reckoned, if not legally impossible.

So Jules and Eddie Trump replicated what they’d already mastered at Williams Island: conjuring something from nothing, while simultaneously bringing their legendary instincts for customer service to the hospitality industry for the first time.

Before Jules and Eddie Trump built the Acqualina Resort & Residences, Sunny Isles was a strip of run … [+]

Couresty of ArX Solutions

Jules’ and Eddie’s vision all pivoted around the word “Acqualina”—which roughly translates into “tender water” or “water’s edge”—and a ramshackle, 5-acre motel on the beach with almost a 1250’ of private, pristine Atlantic Ocean waterfront. In 1997, after years of haggling with the owners, Jules and Eddie finally gave them an offer they couldn’t refuse and closed (“They made a killing”, Jules recalls).

In its place over the next three years, the Trump brothers developed a 51-story ultra-luxury hotel and condo project on the beach that they called the Acqualina Resort & Spa (since rebranded Acqualina Resort & Residences), purpose-built around a design approach that Jules likes to refer to as “inside out”. After years of researching the Ritz-Carlton, Four Seasons, and the most exclusive boutique hotels in the world, the one thing Jules and Eddie came to understand is that nothing is more important to people than a sense of place and that nowhere is that feeling more evocative and emotional than the space within which one lives (that instinct has proven to be particularly prescient during the age of COVID-19).

Jules’ and Eddie’s “inside out” design approach favors natural light, open flow, and the highest end … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

A seamless, natural relationship between inside and outside space is one of the hallmarks of Jules’ … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

So at Acqualina Jules and Eddie focused their time, designers, and money less on the splashy glass and steel that screams “I’m here!” from the outside, and more on the finely-tuned details of what Acqualina’s living experience would feel like on inside—from floor plans, flow, and views to the furnishings, fixtures, and final finishings like leather coated wardrobes and perfectly balanced lighting.

In 2006, Acqualina Resort & Spa opened to rave reviews and hasn’t missed a beat since, including being awarded a Forbes 5-Star rating, the only AAA Five Diamond status in South Florida, TripAdvisor’s Top Oceanfront Destination six times in a row, and most recently USA Today’s Readers’ Choice Awards for #1 Best Destination Resort, #1 Best Waterfront Hotel, and #1 Best Hotel Spa in the U.S.

Acqualina Resort & Residences has received more 4-star and 5-Diamond awards and accolades than … [+]

Courtesy of Benjamin Edelstein/Acqualina Resort & Residences

Never to rest on past success, Jules and Eddie followed up the Acqualina Resort & Spa with an all-residence, uber-luxury, 79-unit high rise right next door that they called The Mansions at Acqualina, which opened in 2015 after more than six years of design and construction. Having nailed their hospitality identity by this point, The Mansions gave Jules and Eddie an opportunity they’d always dreamed of—to design “the finest residences in the world”.

Six years later, nothing embodies that vision more than The Mansions’ two single-story penthouses on the 47th and 48th floors which both sold for $27M+ within months of the building delivering. Each boasts two grand salons, four balconies, a chef’s outdoor kitchen, a cantilevered, private glass pool jutting out over the building’s edge, Fendi, Bentley, and Baccarat finishes, and unobstructed ocean views all the way to the Bahamas.

“We set out to create the finest high rise residences money could buy based on a vision of mansions in the sky,” says Jules of the project. “I live on the 40th floor there so I am pretty sure we can say with confidence that Eddie and I pulled that off.”

Wink. Again.

Jules Trump still wakes up at 5:00 am every morning, works out on the beach, reads relentlessly, is … [+]

Courtesy of Acqualina Resort & Residences

While all of this was going on, Jules and Eddie never took their eye off investing in other businesses. Growing up in the turmoil of South Africa after WWII through the 1970s taught the brothers a vital lesson in wealth and legacy building early on—never gamble it all on red.

“Eddie and I have bought, owned, and sold multiple retail business over the years,” says Jules. “From fashion, bowling, auto parts, home improvement, and medical benefits to wholesale distribution, hotels, fertilizer manufacturing, fitness, and mattresses. The key was always to find businesses that had good fundamentals but could benefit from better customer service. That’s always been where Eddie and I found value.”

In the intervening years, Jules and Eddie, along with Jules’ wife Stephanie, have also dedicated a significant amount of their time and entrepreneurial fortunes to charity and philanthropic endeavors through their Trump Foundation, including founding Miami’s I Have A Dream Foundation chapter for which they host an annual fundraising gala at Acqualina every year that raises upwards of $1M for youth education opportunities in their surrounding communities.

The Trumps’ contributions to STEM education have been even more eye-popping. In 2011, the family donated $150 million spread out over a decade to improve the quality of mathemetics and science instruction in Israeli schools that’s resulted in the training and hiring of hundreds of new teachers in cooperation with some of the country’s leading universities and educators.

The new two-tower Estates At Acqualina which opens this year gave Jules and Eddie Trump the … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

Never to be outdone, Jules’ and Eddie’s newest project, the two-tower Estates At Acqualina which opens this year, gave the brothers Trump the opportunity to intentionally lift their own bar again, this time just north of the hotel, where they were able to bolt another 5.6-acres and 2000’ of private beachfront onto their now sprawling Sunny Isles enclave by buying out an aging time share next door.

“It only took eight years,” Jules jokes. “We had to personally buy out 4,000 different sellers who all held some type of fractional ownership. There were a few last hold outs in the end. But everyone has a price . . . Talk about the ‘Art Of The Deal!’”

Jules’ and Eddie’s “inside out” design approach has resulted in one of the most ultra-luxury … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

There isn’t a single square inch of real estate at the Estates At Acqualina that hasn’t been given … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

Now, almost three years into construction and less than six months from delivering the first units, to say that “no expense was spared” at The Estates would be the understatement of the year—even by Miami standards.

It all begins in the lobbies which were conceived down to every last metallic swan pattern printed on the walls by famed internationally award-winning designer Karl Lagerfeld. “Working with Karl was one of the most deliberately creative processes I’ve been involved with in my life,” says Jules of his experience working with Lagerfeld. “I’d sleep in my lobbies if I allowed it. They’re beyond amazing.”

The signature lobbies designed by international design icon Karl Lagerfeld were one of his last … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

The Trump brothers’ signature “inside out” design approach also remains true to form in all of the Estates’ residences by emphasizing open space, natural light, varying floor plans, ocean views from every room, interior furnishings by Fendi Casa and Trussardi, and an exclusive partnership with La Cornue—a hand-crafted French chef’s range manufacturer from Paris. Each of the Estates’ towers also features 2-story penthouses with private pools as well as a few single-family estate homes on the ground floor that have private access directly onto the beach.

Pre-sales for The Estates’ northern Boutique Tower just started last year where residences range from 4,385 to 9,134 SF and start at $6.3M. The Estates’ South Tower is already 85% sold with the penthouses starting at $31M.

The 45,000, $60M dedicated amenity building Jules and Eddie call the “Circus Maximus” is at the … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

Avra Miami, the renowned Greek restaurant’s fourth U.S. location, will bring a new level of cuisine … [+]

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

At the center of it all between the development’s two soaring glass towers is Jules’ and Eddie’s crowning achievement: a $60M dedicated amenity palace affectionately called the “Circus Maximus”. The four-story, 45,000 building includes a bowling alley, Formula One simulator, surfing pool, movie theater, indoor ice-skating rink, 13,000 SF fitness center, three outdoor gyms, live Wall Street trading room, soccer, basketball, and bocce courts, two-story speakeasy, and a just announced award-winning Greek restaurant called Avra anchoring the ground floor on the beach, the restaurant’s fourth U.S. location in addition to Beverly Hills and Manhattan.

Money might not buy happiness, but if you’ve got three kids or ten grandkids under the age of ten it’s a pretty sure bet that the Circus Maximus does.

“We’re investing more money in our lifestyle experience and amenities that anyone has ever done before and going above and beyond what can be found anywhere else and we’re offering this to only 264 families,” says Jules with a rare whiff of pride. “Our residents are all self-made in one way or another and they’re too smart for renderings or cheap real estate tricks. Anyone can sell glamour because glamour is superficial. What we’re selling is a way of life, and because of that we have to deliver the finest product and experience in our residences that money can buy. It’s taken Eddie and I 40 years to learn how to do that.”

The bowling lanes at the “Circus Maximus”

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

Who doesn’t like ice skating after spending a few hours surfing in the wave pool?

Courtesy of ArX Solutions

It would be at this precise point in life that most people of Jules’ age and net worth would pack it in, retire, and spend more time on his private beach with Stephanie and watching the pelicans dive.

Yet, even at 77, Jules still wakes up at 5:00 am every morning. After coffee, he takes two hours to spend time with Stephanie and read the Wall Street Journal before his day gets consumed with construction calls and around the world Zoom meetings. Three days a week of personal training on Acqualina’s lawn by the beach doing pushups, planks, stretches, and high-intensity cardio keeps him feeling as young and focused as ever. When he’s not working, he reads, listens to podcasts, and Zooms constantly with his three children and 13 grandchildren.

On the real estate side, the Miami market has never been hotter thanks to the pandemic. Branded developments are booming. Companies like Goldman Sachs and venture capitals firms from Palo Alto are all moving south. And at the UHNW end of the market where Jules and Eddie have now made their mark for decades, there’s never been a wider pool of potential buyers.

So will the “other Trumps” ever retire?

“Not any time soon,” says Jules, smiling like he’s hiding some secret he already knows. “What Eddie and I do here is too much fun and we can still raise the bar again.”

Knowing Jules and Eddie, one-upping their own Circus Maximus is probably only a few years off.