So you’re going to a dinner party, or a birthday fete. Once everyone has compared vaccination sagas, what’s the table talk?

The weather, so perpetually pleasant, can’t carry you for 30 seconds.

You steer clear of religion and politics — especially politics, lest you wind up with full-throated, cross-table shouting matches, or every guest slinking home in depressed silence.

So where, inevitably, does the conversation gravitate?

For almost 150 years, it’s been Angelenos’ universal Topic A. Buying it, selling it, looking at it, yearning over it — a pastime, a hobby, and a preoccupation, and everyone has a story to tell. It’s a genre in reality TV. It was the founding impetus for our once-vast streetcar system, built at the outset not to carry people to where they wanted to go, but to where its real estate mogul-creator wanted them to go to buy his property.

To live in Southern California without owning the walls around you is to feel, however slightly, short-stinted, cheated of its illusive promise of even a modest house for people of modest dreams and means: a cottage or a bungalow or ranch house, with a bit of yard for the leisurely life of California.

There are places in the country, in the state, where “million-dollar house” still sounds like a lottery-ticket fever dream, but L.A. isn’t one of them. Today, what was once a working family’s dream home, like the two-bedroom houses in the planned postwar city of Lakewood, is now a “starter” house, priced at a lunatic $700,000 for under 900 square feet.

And what was in the 1950s and ‘60s a stylish, upper-middle-class house in a beautiful banlieue like Pacific Palisades or Brentwood, a well-windowed, one-story place of three or four bedrooms, harmoniously set in a ramble of lawn, and maybe adorned with a swimming pool, is now sale-priced in the millions as a fixer-upper or a tear-down.

The Cheviot Hills house where Ray Bradbury lived and worked for a half-century was demolished in 2015. Its new owner delivered its epitaph to KCRW: “It was not just unextraordinary, but unusually banal.” Its replacement was described by that other Times newspaper as “a hyper-modern box of metal and glass” with carved metal panels bearing Bradbury quotations.

We’ve been forced to work up a new vocabulary for grandiose new places: one is “McMansion.” It was dreamed up in the 1980s, the decade of big hair, big shoulders and big movies, and it means any big, gaudy, prefab-looking house built practically lot line to lot line, top-heavy on its modest footprint of land. It was not a term of admiration.

“Mega-mansion” distinguishes a place from the merely large, or from the upstart McMansion. It’s a place running above, oh, 12,000 or 15,000 square feet. In the past, a house that big would have been called an estate, because it would have been set amid grounds, plural, gardens, plural, and double-digit acreage.

Estates were the “mega” of their day, when L.A. land was cheaper and more abundant, and people didn’t seem to need two bathrooms for every butt in residence. The Times wrote reverently in May 1915 of a French Renaissance-style house going up in Hancock Park, “one of the finest residences” of the year, built of brick and slate, with a 75-by-65-foot footprint. Today you can find — but not afford — houses with master suites as big as that.

Silent-film stars splashed out for lavish houses, none grander than Greenacres, comedian Harold Lloyd’s estate in Benedict Canyon, inaugurated in 1929 with a four-day housewarming party. The 44-room home, with a still-striking garden pool, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

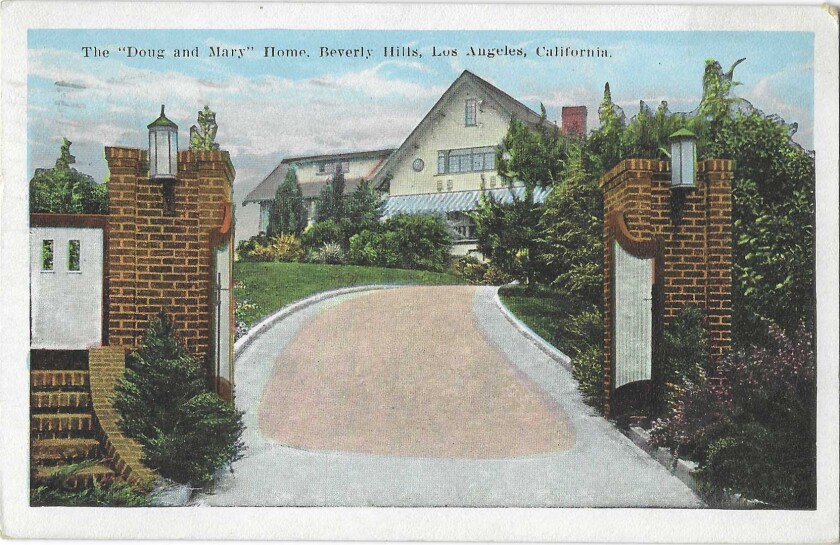

The most famous estate west of the Potomac, with the maybe-exception of Hearst Castle, was Pickfair, in Beverly Hills, the home of two of the most famous people in the world: silent-film stars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks.

A vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection with a 1924 postmark shows Pickfair, the home of Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford.

Save for its price and scale, the story arc of Pickfair’s life and death is typical L.A. Before World War I, it was a hunting lodge and land bought for $3,000. A year after the war, it was the $35,000 home of Hollywood’s First Couple, growing from a half-dozen rooms to more than three dozen, and plural stables, servants’ rooms, tennis courts, garages. After Pickford died, in 1979, it sat unsold, too small and pokey for modern celebrities. Lakers owner Jerry Buss bought it and fixed it up; Pia Zadora and her husband bought it and knocked it down. First she blamed termites. Then she blamed a ghost.

Beverly Hills was still a wilderness when Pasadena’s “Millionaires’ Row,” on wide, leafy Orange Grove Boulevard, was set with so many stately homes that in September 1914, at the request of august residents like Mrs. Montgomery Ward, Pasadena banned double-decker tour buses from making slow drive-bys.

Thirty years later, these showplaces were white elephants, and the heirs of those monarchs of industry were begging Pasadena to rezone the street for apartments.

The Times, ever devoted to its vision of L.A.’s plummy future, wrote pages and pages about real estate, larding its stories with words like “stately mansion” and “palatial dwelling.” In August 1914, it paid homage to a “grand” new house built for the Connelly family on its land in South L.A. where the Connellys used to graze sheep — 16 rooms, not counting bathrooms, fireplaces in every bedroom and in the vast reception rooms. The mayor’s official residence, the 1920s Getty Mansion, built on an acre of land in Windsor Square for a member of the oil family, stands at about 6,300 square feet, some of that devoted to public rooms for official entertaining. When it was given to the city in 1975, it was appraised at $240,000.

We’ve been conditioned to think of L.A. real estate as endlessly more valuable. That’s fine if you’ve already got some, but if you’re trying to buy your first house, that seems like the “Through the Looking Glass” promise of jam yesterday and jam tomorrow but never jam today.

Long ago, though, Los Angeles had more land than takers. At one point in the 1860s, land around where MacArthur Park now stands was offered at a public sale for 25 cents an acre, and no one bought it — too far out of town.

The ease of new transcontinental train travel brought thousands of prospective Angelenos here. They were met at the train stations by salesmen flogging lots in what were sometimes to be found in phantom towns that didn’t exist and never would. Yet people bought and bought and bought, and in a matter of months, or weeks, an acre of land might go from $10 to $100 to fifteen times that. In 1887, land sales transactions in L.A. County totaled $100 million.

After about 30 months, the bubble popped and the land values deflated. L.A.’s appetite for land paused for breath, but it wasn’t sated.

So we come to that third new vocabulary word: the “giga-mansion.” Because it turned out that there was something more mammoth than “mega.”

In the late 1980s, the building saga of TV mogul Aaron Spelling’s new 56,500-square-foot giga-mansion in Holmby Hills was followed like the soap opera it was. “Candy Land,” people called it, for Spelling’s wife’s name.

It represented everything that fascinated and repelled and attracted people about L.A. “People do not want to live in tight spaces,” developer Brian Adler told The Times back then. “There’s a real trend right now: ‘Give me room.’”

Yet on her “90210MG” podcast this year, the Spellings’ daughter, Tori, told listeners that “We literally as a family spent the time in the kitchen, my mom’s office that we all congregated in, and our bedrooms. And that was it.”

It was enough of a window into L.A. that Joan Didion wrote about it in the New Yorker, mentioning the often-denied rumor that, partway through construction, Mrs. Spelling wanted the foundation lowered so she would not have to gaze upon the sign on the Beverly Hills Robinson’s department store from her bedroom window.

The place had a bowling alley, a doll museum room, a barber shop, and a gift-wrap room. It didn’t have a roof, it had a “roofing system.” Thereafter, it was as if the super-rich needed to find crazy stuff to spend their house-money on: a full-sized basketball court, aquarium walls, sunken tennis courts so the wind wouldn’t send a serve veering off the court, room-sized closets with windows to see colors in natural light. Elevators, waterfalls, mechanical bulls, tanning rooms, cigar rooms, rock-climbing walls. A helipad? Why not?

People seemed not to mind vulgar excess, so long as it wasn’t shoved in their faces, which it was at a can’t-miss-it Sunset Boulevard mansion near the Beverly Hills Hotel.

In the late 1970s, its young owners, a 24-year-old sheik and his 19-year-old wife, filled the large outdoor urns with plastic flowers, and painted the white classical nude statues on the front veranda in what were delicately called “natural skin and hair tones.” Indelicately, it meant dark pubic hair and bright rosy nipples. Tourists gawped and giggled. Beverly Hills was not amused, and neighbors were popping corks when the house was leveled in the 1980s.

Prices rose, yes, but so did neighborhood momentum against these giant edifices jutting up in their midst. Even as the Spelling construction saga was kept alive by lawsuits, Glendale neighbors of a suspiciously overlarge new hillside house learned that a city investigation concluded that “favoritism and incompetence” had allowed a big spender to build more than twice the square footage that the city had approved. Remedying those code violations kept the place uninhabited for years, but at least a local high school raised some money by charging people to tour it. Glendale neighborhoods still wave the memory of the place in their anti-mansionization campaigns.

Perhaps the most famous warrior in these fights was Oscar-winning actor Jack Lemmon. Of the 8,000 people in Beverly Hills who signed a petition in 1993 against the construction-site work and tree-cutting for a five-story, 18-bedroom, 46,000-square-foot house on Lemmon’s narrow, hairpin road (and that was its scaled-back size), he was the most persistent.

At the City Council meeting that voted down the project, Lemmon was joined by Jay Leno, who joked about “millionaires fighting billionaires,” but who pointed out that he had yielded to neighborhood sensibilities when he decided not to build an immense garage there for his car collection.

Lemmon told The Times in 1993 about “fortresses stuck among the neighborhood … Suddenly there’s a teardown, and they rebuild with a thing that looks like it could house 100 people.” Lemmon had lived on the street for more than 30 years, in a 1936 house whose 6,000 square feet and cozy rooms and covered patios resembled a 1936 rich man’s idea of a big house, not a 1993 version. (I have spent some truly amusing evenings at the Lemmon house, so I can say this firsthand.)

Prices of these humongous houses didn’t creep up. They leaped. Real estate writers had hardly hit the “send” key on a story about “record price for a house” when some other sale could follow on to top it. The 2019 record price of $150 million that one of the Murdoch sons paid for the “Beverly Hillbillies” mansion in Beverly Hills was overtopped two years later for the $177 million that a venture capitalist forked over for a Malibu spread. The sale of one single mega-house easily topped the $100 million in total land sales recorded in Los Angeles County in the year 1887.

It’s impossible to write about these staggeringly absurd home prices without pointing out the unlovely truth that Los Angeles is also where tens of thousands of people have no home at all, and many thousands more strive like mad to keep theirs — all in one of the most ridiculously unaffordable cities in the world. I put this drift to extremes out there for you to wonder at its consequences.

All right, then. Now, here is some guilt-free schadenfreude for you, instances when high-flyers have taken an Icarus nosedive.

- “The Mountain,” 157 hilltop acres in Beverly Hills, bigger than the Los Angeles County Arboretum, graded away of enough dirt to fill the Rose Bowl twice over, with enough left over for the Greek Theatre. Through many hands and debts, the property, once priced at a billion dollars, was sold in 2019 at a federal foreclosure auction in Pomona for a pocket-change $100,000 to the estate trust of a much earlier owner. (If you’re kicking yourself for not being there to bid, don’t — it came with $200 million in strings attached from debts owed to the same previous owner.)

- “The One” is a massive Bel-Air spec house whose dream price shriveled from a half-billion-dollar ballyhoo to a $259 million asking price to last month’s bankruptcy auction bargain of $141 million last month. A fast-fashion mogul bought the 105,000-square-foot house, which is technically still a fixer-upper after almost 10 years of work, and who-knows-how-many creditors whose work was unpaid, getting hung out to dry. Some of those creditors failed to persuade the bankruptcy court judge that the bid should be nullified because Russia had just invaded Ukraine, and a lot of bidders were scared off by the uncertainty of world politics.

- This month, the man who built an ill-starred Bel-Air house the neighbors named, and not flatteringly, the “Starship Enterprise,” took a guillotine-sized haircut on 66 acres that he had priced at $130 million. They went for $35 million at a bankruptcy auction. Mohamed Hadid’s contumacious construction of the 30,000-square-foot “Enterprise” house violated so many city building regs, like size and height, that in December 2019, a judge agreed with neighbors that it constituted a danger to the public and had to be torn down. The hubris pull-quote of this tale is Hadid telling Town & Country magazine, “This house will last forever. Bel-Air will fall before this will.” Hadid pleaded no contest to criminal misdemeanor charges. The “Enterprise” was priced last year at $8.5 million but sold for $5 million to a development company that, per the judge’s order, is taking the place back to the ground.

I suspect one reason we like to linger over real estate we can never afford is because there is such a dearth of spectacular public buildings in Los Angeles, where so many decades of renowned architects’ talents have been showcased in private houses that we never see up close.

There is one place, built as a private home and now a public place, that might have earned the descriptor “haunted,” if anywhere in this sunny, modern city does.

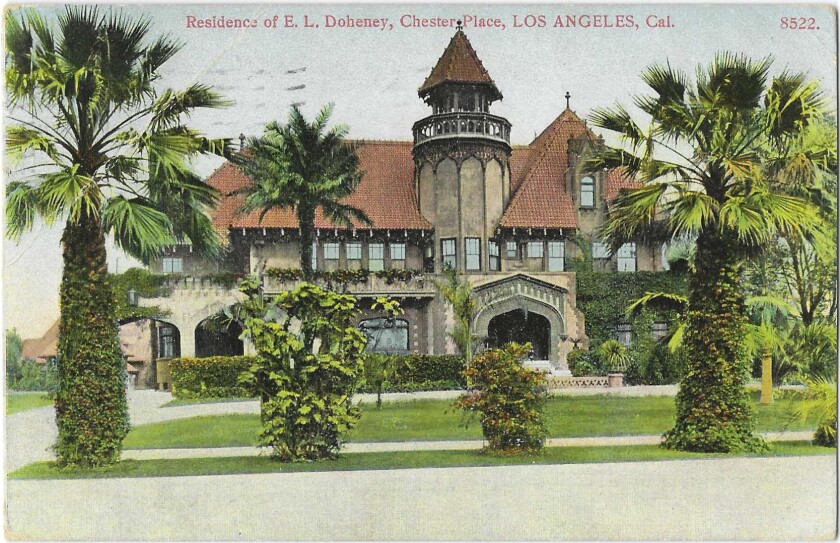

The Greystone Mansion was built in Beverly Hills by disgraced oilman E.L. Doheny, who himself lived in a not-too-shabby mansion on Chester Place in L.A.’s West Adams neighborhood.

A vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection with a 1908 postmark shows the home of oilman Edward Doheny in one of L.A.’s first gated communities near the USC campus.

Doheny, impugned but not impoverished by the Teapot Dome scandal, spent $4 million to build Greystone as a gift to his son and heir, Ned. It had every luxury of the time and more: two tennis courts, English gardens, Italian gardens, an 80-foot waterfall cascading into a manmade lake, and a staff of more than 30 to take care of it all. The lawns were so vast that, like a farmer who never gets to stop painting one side of his barn every season, gardeners had no sooner finished grooming the end of the lawn than they had start anew at the beginning.

In early 1929, only a few months after the young Doheny family moved in, Ned and his friend and factotum, Hugh Plunkett, were both shot and killed in a guest bedroom. Notwithstanding questions and conflicts about the circumstances and evidence, the official version was murder-suicide committed by Plunkett.

Ned’s widow lived on in the house for about 25 years, and in the 1960s, at the prospect of the mansion being demolished by a new owner and the grounds subdivided, Beverly Hills bought the place and turned it into a public park.

Greystone was so substantially built that behind its walls ran passages big enough for workmen to move quietly and unseen, to repair any problems with plumbing and wiring. The Doheny children used them for games of hide and seek. Timothy Doheny, who was 2 years old when his father died, remembered in 1984 that “I never got stuck. But I dreaded it, really did. Nobody would hear you, and you would be a skeleton by the time you were found.”