The Palos Verdes Peninsula — a land of rolling hills, jagged cliffs and sweeping views of the city and ocean — boasts some of the most beautiful terrain in Southern California.

It’s also long proven to be some of the most dangerous.

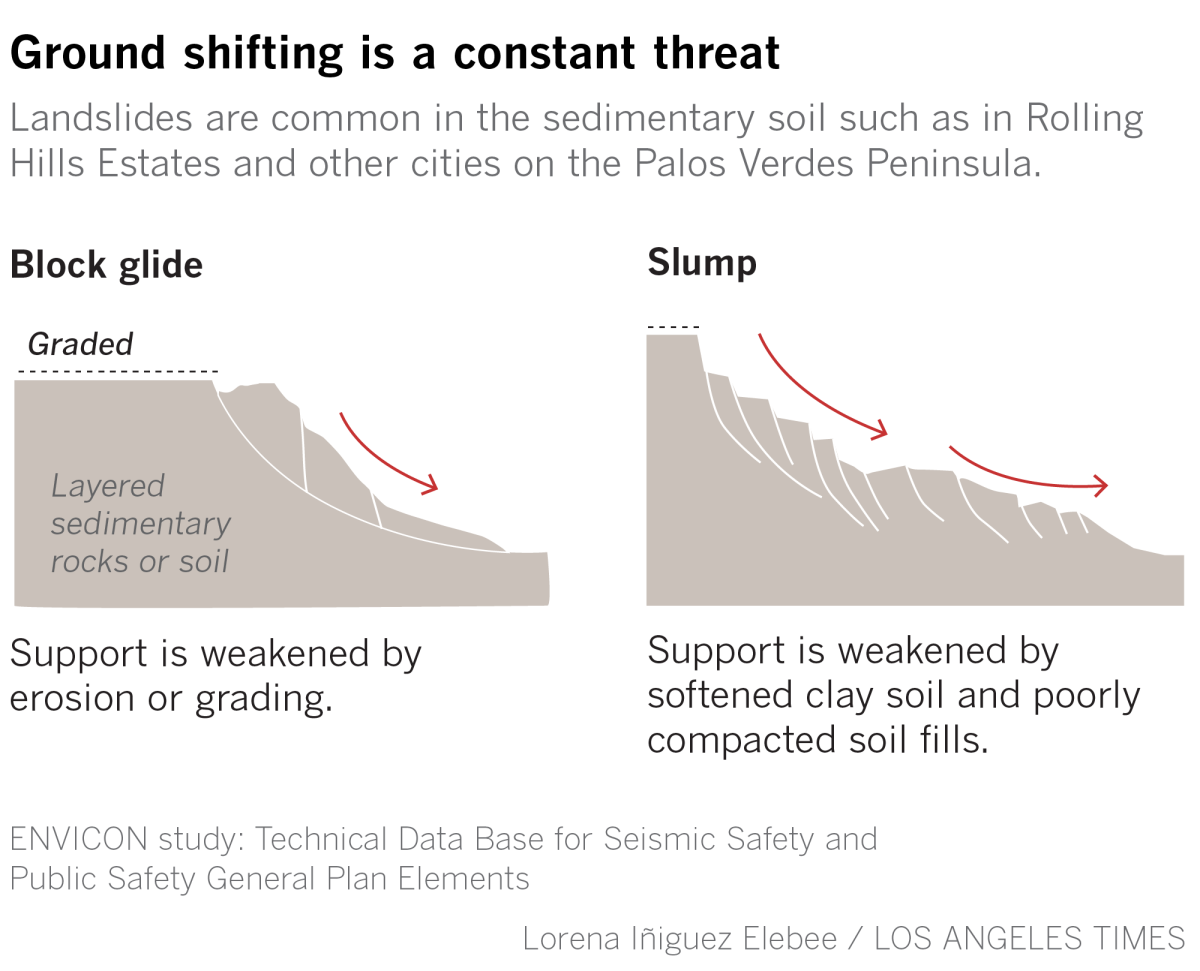

For hundreds of thousands of years, the peninsula has been plagued by an ancient landslide complex that slowly reshapes the topography. The earth lurches and warps, sometimes slowly, sometimes rapidly, destroying homes and infrastructure along the way.

The latest damage was dealt to Rolling Hills Estates, where a major ground shift led to 12 homes being evacuated after a fissure snaked its way through the neighborhood. Foundations cracked, walls collapsed and some homes were visibly leaning as the hillside upon which they were perched slowly descended into a canyon.

Land movement is a stubborn, if periodic reality for much of California, particularly the coastal hills of the South Bay and Orange County.

Laguna Beach, Laguna Niguel and San Clemente have dealt with destructive slides. In the 1920s, a handful of homes in San Pedro slid into the ocean, creating what’s now known as the Sunken City. A mile south of Rolling Hills Estates, the city of Rancho Palos Verdes is hatching plans to avoid a similar fate.

“This remains an active situation,” said Rolling Hills Estates Mayor Britt Huff at a city council meeting on Tuesday, adding that due to a break in a sewer main, five additional houses were ordered to evacuate earlier that day.

At the meeting, the council declared a state of emergency in order to access broader resources from state and federal agencies.

“No one expected this. Landslides don’t really happen in this area,” said resident Lisa Zhang.

A landslide-prone peninsula

The peninsula’s bout with landslides is well-documented in the geological record, stretching back millenniums but coming to a head 67 years ago when an L.A. County road crew accidentally reactivated an ancient slide complex while building an extension of Crenshaw Boulevard in Rancho Palos Verdes.

The crew dug up and shifted thousands of tons of dirt, throwing things off balance enough to send the land in the Portuguese Bend into a super-slow-motion descent and activating a landslide.

That’s just one ancient landslide complex. According to El Hachemi Bouali, assistant professor of geosciences at Nevada State College who co-authored a report on the Portuguese Bend landslide complex, there are areas all across the peninsula at similar risk.

Due to precipitation and geology, the hills are uniquely susceptible to movement. Layers of clay — bentonite and montmorillonite, to be specific — are found beneath the ground, interspersed between layers of bedrock. When water absorbs into the earth, it expands and lubricates the clay until it’s slippery enough for the land to ride downward with the force of gravity. Even thick layers of bedrock will slip.

Water infiltrating the earth is the most common cause of landslides, according to Brian Collins, a research civil engineer with the U.S. Geological Survey. In California, these types of landslides are typically triggered during a big rainy season.

But there is another factor at play. The Palos Verdes Peninsula — like Laguna Beach and San Clemente — is packed with people. Those people have sprinklers, gutters, irrigation systems and leaky pipes that all add water to the earth.

Inland, an area as hilly and craggy as the Palos Verdes Peninsula might not be expected to house roughly 65,000 people. But anywhere with a view of the ocean, with secluded canyons to hike and ride horses in, will always be attractive — especially right next to L.A.’s flat sprawl.

What caused the slide?

There’s no official diagnosis on what caused the landslide. According to city officials, a geologist will study the site and draw a conclusion from there, reviewing both the history of the area and any recent changes to the land.

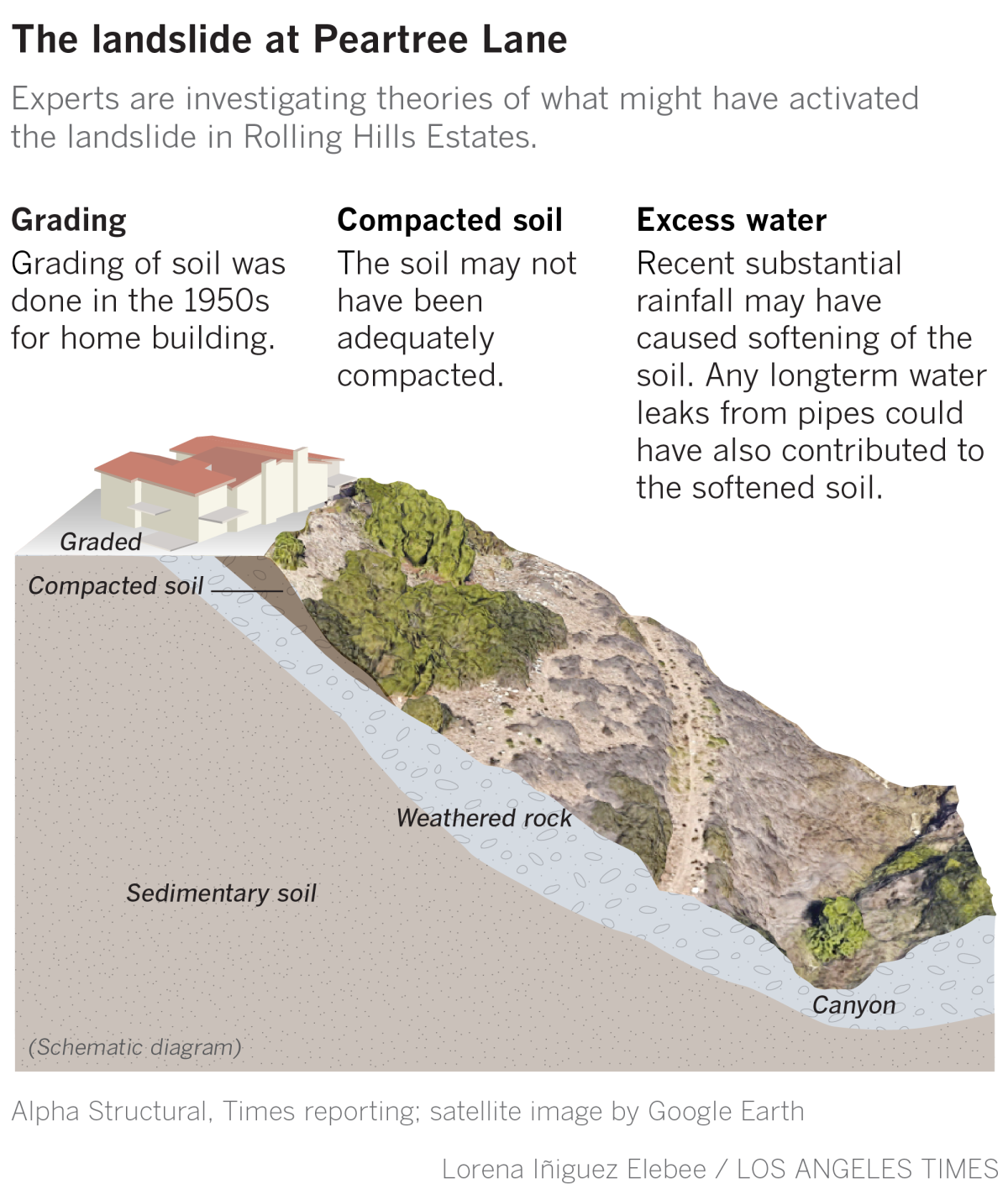

But geologists and structural experts have tossed out a few likely culprits: land grading, rainfall or something as simple as a busted pipe.

The townhomes destroyed in the landslide were built in the 1970s, and according to Kyle Tourje, a structural assessor with Alpha Structural, much of the land was graded and reshaped to make room for buildable lots starting in the 1950s.

So even though lots might be relatively flat, if land was moved in order to make it flat, the soil might not be as compact as it should be. When soil is looser, it’s more susceptible to water.

Tourje said the record rainfall of winter and spring didn’t help, but he thinks the slide was likely caused by a concentrated water source such as a broken pipe or sewer drain.

“On a big graded tract like this, one line that feeds one sink of one single house can affect the soil,” he said. “Next month, your water bill is extremely high. Next thing you know, your house is at the bottom of the canyon.”

Tourje works on landslide damage every week but only comes across slides of this magnitude a few times per year.

“This is a total loss. These homes will have to be completely demolished,” he said.

Bouali, on the other hand, says unless a smoking gun appears, such as a burst pipe or a resident’s $1,500 water bill for June, he’s leaning toward rainfall as the primary culprit.

“My guess is that there has been a slow decrease of the slope’s resisting forces due to infiltration of precipitation into the clay layers,” Bouali said, adding that even though the rain fell in the spring, it might take until July for the water to flow through the layers of clay.

He points to California’s Landslide Susceptibility map, which shows almost the entire peninsula as highly susceptible. Given the area’s geological makeup, as well as the roughly 20-degree downward slope upon which the homes were perched, the landslide didn’t necessarily come as a surprise.

Since the ‘70s, regulations have become stricter with limits on how steep builders can grade lots and requirements for more subsurface drainage systems and more compact soil.

But those measures might not help if the slippery layer is 60 feet underneath all the grading and maybe several strata of bedrock, according to Tony Lee, a local geologist who has worked in the area for 30 years.

Lee said most of his clients come from other areas of the peninsula where slides are more prevalent, but he’s already received multiple calls from homeowners in Rolling Hills Estates wanting to get their properties checked.

The allure of living in a landslide zone

Common sense might suggest that the land is uninhabitable — that building homes on terrain prone to landslides will inevitably lead to disaster.

But California is a beautiful place, and Californians love looking at it. It’s the same reason that hillside homes are perched on stilts in a region that deals with devastating earthquakes. The same reason buyers flock to the fire-prone hills of Malibu or the Western Sierra or cram beach houses onto the sand as ocean levels rise.

“I’ll be here until I can’t be here anymore. I’ll slide away with the land,” said Claudia Gutierrez, a longtime resident of Portuguese Bend, an area about a mile southeast of the slide site that has been dealing with landslide issues of its own.

If the Rolling Hills Estates landslide is the hare, moving quickly and aggressively, then the Portuguese Bend landslide is the tortoise, with the land slowly shifting roughly eight feet per year for the last 15 years.

It has caused chaos in the community, with houses sliding across property lines and roads warping into roller coasters. But according to Gutierrez, that hasn’t kept people away.

“We had homes in the middle of the active landslide zone that sold for more than $2 million last year,” she said. “I’m amazed.”

For newcomers, the peninsula offers not only great views but stellar schools, cool coastal weather, larger lots and a more relaxed, rural feel compared to the bustling cities surrounding it. And for longtime residents, even though they’d be able to sell their houses, the peninsula has become home — even if that home is slowly slipping out from under them.

According to local real estate agents, the landslides have never been a major concern to residents of Rolling Hills Estates.

“People think this was an isolated incident,” said Mingli Wang, a longtime real estate agent in the area. “People believe their homes are safe. They don’t think it’ll happen to them.”

She noted that during home sales in the city, sellers disclose natural hazards such as the area being high-risk for fires or a dormant earthquake zone. But landslides are not part of the disclosure.

Wang is a resident herself, and she’s not concerned about the community’s safety going forward.

Steve Watts of Vista Sotheby’s International Realty said that landslides are never part of the conversation during a sale in the city.

“If your house is hanging off the edge of a cliff, they’ll sometimes get a soil report to check how deep the bedrock is. But it’s very minor,” he said.

Watts said the gated neighborhood where the homes slid into the canyon might see a slow market in the short-term, but sales will be back to normal before long.

Zillow puts the median home value in Rolling Hills Estates at $1.918 million, nearly double the $1.067-million mark set in 2015. Many homes in the city face Torrance, missing many of the ocean views featured elsewhere on the peninsula, but still fetch prices north of $5 million. The cheapest single-family home currently on the market is offered at $1.8 million.

When Bouali, the geologist, leads classroom discussions about hazardous areas, the conversation inevitably leads to the question, “Why do people even live there?”

He said it often comes down to the cost of moving. And Southern California has an additional factor: most of the region deals with some sort of natural disaster risk, whether it’s a landslide, flood, wildfire or earthquake. Pick your poison.

That said, he added that he wouldn’t personally live on the peninsula.