‘Key workers’ – A term that has barely been used before the Covid-19 pandemic has become omnipresent in the space of just a few months. However, those that are so essential to keeping society running, are often among those who earn the least and cannot afford to live in the centre of large cities such as London.

Skyroom, a new venture launched by entrepreneur and Forbes 30 under 30 Alumni Arthur Kay aims to solve this problem. Instead of choosing conventional approaches, the company is following a simple principle: If there is little space to build new houses, could we build new homes in the sky instead?

Politicians are vowing to do everything possible to protect key workers and initiatives such as Clap for our Carers and Meals for the NHS offer gestures of support.

The current crisis has brought about a paradigm shift in how the public eye looks at those who keep our cities running: Firefighters, teachers, doctors, nurses, delivery drivers, police officers & bus drivers.

Skyroom concept: Affordable housing on vacant rooftops in Central London.

Skyroom

However, some long-neglected issues have resurfaced. Many key workers barely make enough to make ends meet. Health care assistants start their career with salaries around £18,000 while bus drivers start at £14,000, well below the London living wage.

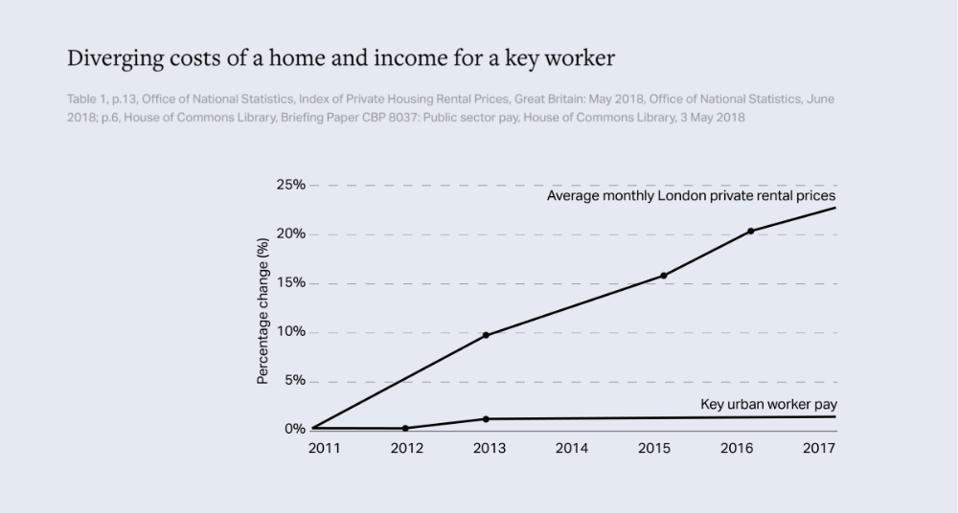

For years property prices have increased drastically in London. This has led to 54% of key workers being forced to live away from Central London, with commutes averaging 2 hours per day.

This makes the provision of key services increasingly complex. Patient care suffers when nurses and doctors are not able to quickly get to hospitals when they are urgently needed. Quality of teaching declines when teachers are exhausted from long commutes and face constant financial stress.

The quality of life, mental health and physical health of key workers are under jeopardy. This doesn’t only have personal consequences, but can negatively affect those that rely on key workers to provide services.

Development of London rental prices vs. key urban worker pay

Skyroom

Arthur Kay, the CEO & Founder of Skyroom observed this issue well before Covid hit, in 2018.

An architect by training, Kay returned to his roots after founding Biobean, an innovative recycling company producing biofuels from waste coffee grounds.

Kay observed that – while London has little vacant space on the ground level to add new housing – there is plenty of space on the rooftops of existing buildings.

He asked himself whether the under-utilized rooftops could be suitable to accommodate hundreds of new homes and whether the housing crisis could be solved by growing the city vertically into the sky.

Arthur Kay, Founder & CEO of Skyroom

Skyroom

Shortly after, Skyroom launched a Whitepaper in collaboration with UCL’s Institute for Global Prosperity and architect Sir Richard Rogers to analyze the problem.

“When we launched the Whitepaper many local and central government officials told us that they found it odd to focus on key worker housing. Covid-19 has changed this fundamentally. Everyone now recognizes that we got to take care of our key workers”

Since then Skyroom has developed a model of affordable, sustainable houses which can be placed on vacant rooftops. Fifteen new homes across London have already reached the planning phase with hundreds more scheduled to be built in the coming years.

Although affordable, the properties are among the most central homes available in London: One of the first properties will be within two minutes walk from Trafalgar Square, overlooking the skyline of London.

To realise its vision Skyroom collaborates with local authorities and registered housing providers. The startup acts as a technology and urban development company while leveraging the expertise of existing players to let homes to key workers.

Skyroom concept designs

Skyroom

While councils offer social housing for the poorest in society and charities like Shelter and companies like Beam tackle the homelessness crisis, key workers often fall into a gap.

“Key workers mostly don’t qualify for council housing. That’s why they are often left to the private housing market, where they can rarely find affordable homes”, says Kay.

Not poor enough for social housing and not wealthy enough to afford a flat in a central location, key workers are left with few alternatives to moving away from the city.

Kay explains: “While there is a lot of initiatives providing housing for different target groups there is currently no government programme for key worker housing. This is the gap we are closing with Skyroom”

The company has developed a range of proprietary technologies which allow them to manufacture homes centrally in a factory, eliminating the need for complex on-site construction projects and lowering the cost of building homes.

“We are able to leverage robotic manufacturing and sustainable materials to build environmentally friendly, affordable homes in a factory. In this way, housing can be provided without the need for construction projects that take years. Instead, homes are built in weeks or even days.”

While Skyroom has bootstrapped their operations from the beginning and has already reached profitability, the company is about to launch the Key Worker Homes Fund in partnership with a large real estate company. The fund will invest more than £100 million in the development of affordable key worker homes.

“This fund will provide the capital to build affordable homes at scale”, says Kay. “It’s also been exciting to see council leaders, such as Kieron Williams, the Leader of Southwark Council, introducing legislation to provide dedicated affordable housing for key workers. We’ve got clear demand, now it’s time to build the homes.”

Life expectancy by location in and around London

Skyroom

Kay believes that there is a broader vision for Skyroom that goes beyond the provision of homes.

“We are not just here to build affordable housing for key workers. I believe that we can make cities healthy and happy places for key workers to live in. It makes a fundamental difference if doctors, for example, come to work feeling well-rested, happy and respected because they live in an affordable, beautiful home close to work. I believe it will have an enormous positive impact on the 50 patients they take care of. This will not just improve the lives of key workers, but all of our lives”.

Arthur Kay and Maiko Schaffrath (the author of this article) both serve on the board of Fast Forward 2030. This article is unrelated to their joint engagement there.