Across the COVID epoch, as we’ve been expanding our range from house-hunkering to house-hunting, we’ve needed decoder rings to translate real estate-speak, a language that’s especially complicated in Los Angeles. How many ways can you hint at the idiosyncratic, even quirky or strange, without scaring off buyers? How to interpret “eclectic”? “Imaginative”? “Distinctive”?

Every home is distinctly the resident’s, but especially in L.A., some of our peak individual inventiveness, along with architectural talent, have been devoted for decades to the single-family home.

That’s what enticed the multitudes here in the first place. You move to New York despite the prospect of living in 400 square feet of a human sandwich. You move to Los Angeles in part because you expect to reign over your own kingdom in miniature — a house, a patio, a chicken adobada in every pot, and an orange tree in every garden.

Merry Ovnick’s insightful book “Los Angeles: The End of the Rainbow,” about the domestic architectural expressions of civic culture, reproduces a 1943 advertisement quoting a letter from a “Sgt. Houston” serving in a foxhole in New Guinea, and dreaming of a “sweet little cottage” he’ll build in California. “It won’t be big but it’ll have every convenience I can cram into it,” and he’ll “stay there the rest of my natural life.”

Or until he upcycles it with a scale model of the fountain of Trevi, or with columns like Monticello, because as long as we’re reinventing our lives in L.A., why not think big about the place where we live it?

The great Southern California sales pitch? Live better horizontally. Next to your neighbor, but not too close, and certainly not above or below. Apartment living could be a temporary circumstance, a career girl or bachelor’s temporary transition to a matrimonial cottage like Sgt. Houston’s, or a solitary elder’s transition to a cemetery’s greensward. In the 1920s, one-third of Angelenos owned their own homes; in 1920, 87.3% of New Yorkers were renters.

Harry Culver, who created Culver City out of whole cloth, told his salesmen that they were benefactors of mankind. “Whenever you can take a family out of an apartment house … and place that family in a fresh, pure, health-giving district in a home of its own … you are not only starting that family out to success, but you are rendering a service to the community and a service to humanity.”

As Robert M. Fogelson wrote in “The Fragmented Metropolis,” Angelenos’ idea of a “good community” was one “embodied in single-family houses, located on large lots, surrounded by landscaped lawns, and isolated from business activities.”

The moral power of the imagery of such neighborhoods is still formidable. In the 1990s, an editor of mine asked me to take a visiting New York editor on an L.A. tour. The visitor specifically asked to see Watts, and so I drove her along the hundreds-numbered streets, with their little stucco and wood-framed houses and duplexes. The kids might sleep in the bathtub if gunfire burst forth in the neighborhood, but there were rose bushes in the frontyards and swings on the porches. No, no, the editor protested to me. “I want to see the slums.”

Our public beauty spots deserve a visit, by all means — the world-class Disney Concert Hall and LACMA, the Central Library and Grand Central Market, the Watts Towers and Wiltern Theatre, and City Hall and Union Station. But it’s the houses that surprise visitors and gratify us, even if they can only be glimpsed from a street or a sidewalk.

There are the glorious ones by Pierre Koening, Richard Neutra, John Lautner, and Rudolph Schindler, the stark and startling ones by Frank Gehry, the playful, Gaudi-inspired O’Neill house in Beverly Hills, and at least a half-dozen Frank Lloyd Wright houses, not reputed to be his best, which is like saying your Van Goghs are not among his best.

Paul Revere Williams, the standout Black architect, designed more than 2,000 homes (too many of them since leveled), some of them for movie stars. In the 1920s, Wallace Neff, another architect-to-the-stars, designed what we can call the Hollywood White House, then the most famous residence in California, save perhaps Hearst Castle. “Pickfair” was the Beverly Hills home of two of the three most celebrated actors in the world, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. Neff also created a house for the third, Charlie Chaplin.

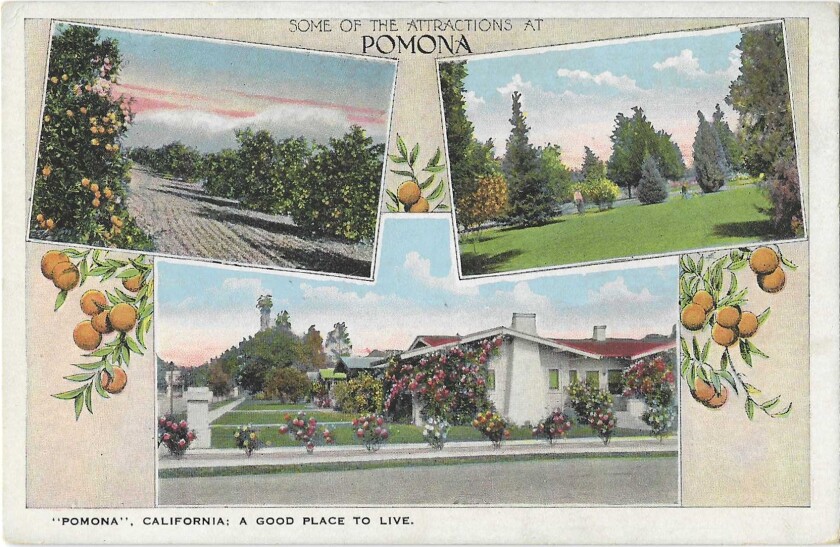

The vigor of real estate salespeople and the chambers of commerce were pitched at the middle classes. South Pasadena was and is a bungalow heaven. To the north, Pasadena has a historic district actually called Bungalow Heaven. Pomona was “the city of fine homes.” The bungalow was already a local trope in the late 1920s, when a Mack Sennett comedy, “For Sale: A Bungalow,” featured a couple of real estate schemers conning a young woman into buying an overpriced bungalow — where she quickly strikes oil.

Pasadena is home to the Bungalow Heaven neighborhood today, and a classic example of the style is seen on this vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

A vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection shows the citrus groves, parks and homes of Pomona.

These humbler homes of Sgt. Houston’s reverie were not necessarily boring, at least not once Angelenos moved into them and after-marketed them. The 1930s’ “WPA Guide to Los Angeles” adjudged us to be “architecturally flamboyant, and even discordant. … Los Angeles architecture is characterized by a flair for the eclectic and the unusual.” But “grotesqueries have been giving way to interesting and important innovations. Particularly is this true of domestic architecture.”

Yet unto the present, these idiosyncrasies have stretched the elastic bounds of taste. It was fine fun for passersby, seeing the straight-up kitsch of the Hancock Park “House of Davids,” where 19 statues of Michelangelo’s naked young Old Testament hero stood for years along the curved driveway. But the new owners de-Davided the house PDQ.

The lords of modest homes simply want to make theirs stand out, but not always to these extremes. Beginning in 1951, Daniel Van Meter brought home hundreds of wooden beer pallets discarded from the Schlitz brewery near his Sherman Oaks home. Just as anyone would, he began building what became a 22-foot tower behind his house.

When the Fire Department ordered him to take it down, Van Meter besought a higher civic judgment — and lo! The city Cultural Heritage Commission bestowed cultural monument status on his tower. “Maybe we were drunk,” explained commissioner and architectural historian Robert Winter. The tower was demolished in 2006, eight years after Van Meter died, convinced to the last of the artworthiness of his tower.

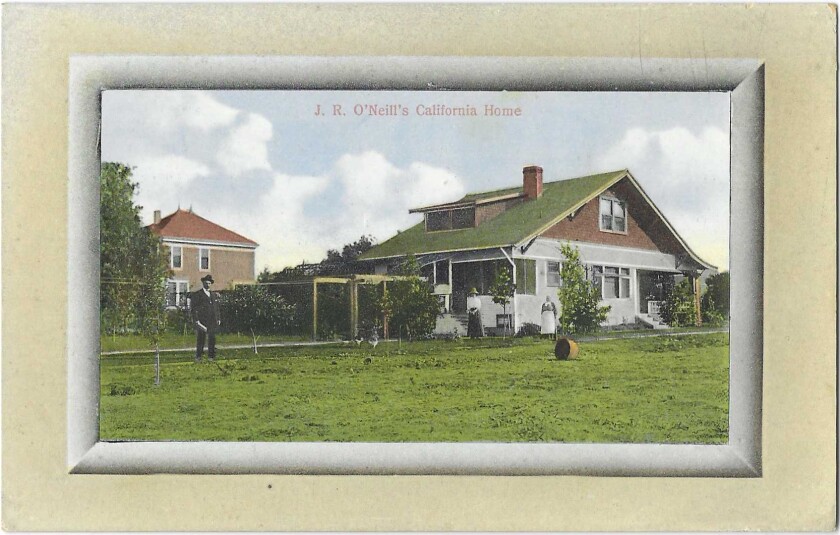

A vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection depicts people standing outside “J.R. O’Neill’s California Home.” The reverse side mentions O’Neill Vineyard Co., 420 West 8th Street, Los Angeles.”

Bad taste is really a kind of solace. For all of those houses you envy and crave, you can make yourself feel better by ridiculing the hideous ones: the bogus hacienda, the house with the simpering wishing well, the drab little cube with pompous, Hampton Court-sized faux-heraldic animals, the houses with so much gaudy gilding that you have to hurry off to the ophthalmologist.

So, as you see, not for old-school Angelenos the replicant conformity of HOA America. I know I’ve cited this remark before, but it’s so trenchant it’s worth repeating: Once, as I was writing about the difference between Los Angeles and Orange counties, I sought out the same Robert Winter. He thought of the hectares of white-stucco-red-tile-roofed subdivisions. “Orange County,” he said, “looks like dentures.”

The postcard industry came into being about the time Southern California was flourishing as a middle-class Xanadu, and some of the first promotional images were the Pasadena mansions of “millionaires’ row,” the winter homes of Gilded Age industrialists like the Busch brewery family, the Gambles of Procter & Gamble, the Montgomery Ward mercantile family, the tobacco baron John S. Cravens.

Flowers are in bloom on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection showing the exterior of actress Ginger Rogers’ Beverly Hills home.

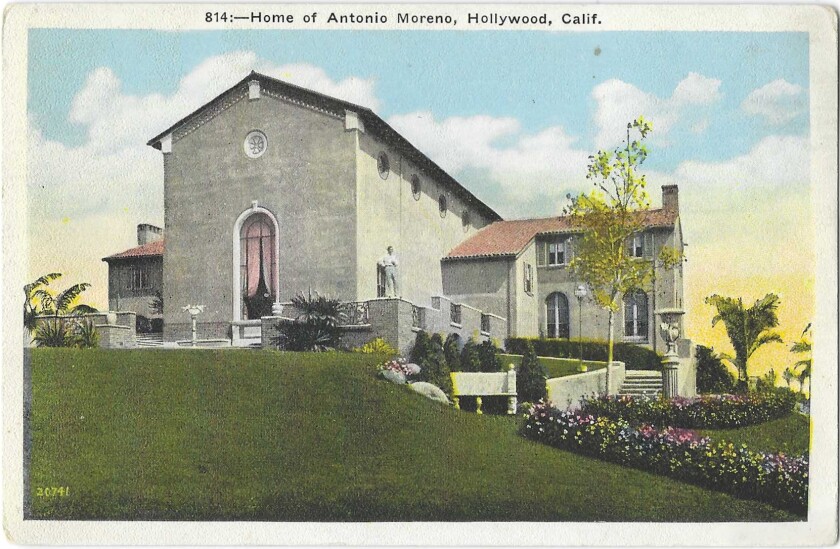

Look closely and you’ll see actor Antonio Moreno — known for “Creature From the Black Lagoon” and “The Temptress” — striking a pose on this vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

But soon, the industrialists’ homes were crowded out by the new money and new and glittering names of Hollywood stars. Postcards — from photographs that could be taken from the public sidewalk — teased the folks back home with houses as glamorous as their renowned residents, some of whom appeared to be posing for fans in front of their dream homes.

Today, some of those homes look modest enough that they’d be guesthouses. Would I lie, or even take artistic license? Before it was bulldozed in about 1990, Pickfair — which had hosted kings and presidents — had been converted into a compound where the guesthouse for the owner’s secretary was larger than the original Pickfair itself. The ghost of Mary Pickford — who banned women from wearing pantsuits at the charity soirees she allowed on her lawns — would have despaired, “Are the shades of Pickfair to be thus polluted?”