AUSTIN, TEXAS – FEBRUARY 19: Mark Maybou scraps snow into a bucket to melt it into water on February … [+]

Getty Images

I live in Dallas, and though we were spared from the last natural disaster that rolled through here, an EF3 tornado right down the street, we were NOT spared from the arctic cold winter storm that swept our state beginning Sunday night when the mercury dipped to 7 degrees.

My biggest concern was the states’ power grid for electricity. I figured we might lose power in some areas, and I worried most about multi-family apartments. I never dreamed, though, how many would be impacted, how it would cross socio-economic barriers, and that we would run low on natural gas since we are the nation’s number one supplier.

When our power went out, we had no heat in the house. No hot water, either. The longest blackout, 16 hours, blew out a tankless hot water heater and froze the pipes behind my washing machine, located on a north wall. When I ran the washer a few days later, water spewed everywhere.

The first blackout occurred at midnight Sunday, ironically, when I was in the bathtub.

Oncor’s Definition of “Rolling Blackouts”

We checked with Oncor, Texas’s largest transmission and distribution electric utility, on our phone apps. Expect rolling blackouts, it said, for 15 minutes to an hour at a time, which we were familiar with from visiting our son in California.

MORE FOR YOU

But that first blackout lasted until 10 am the next morning.

The electricity would come on for an hour or so, then go off for far longer, the longest period off being 16 hours Monday night when the outside temperature dropped to below zero. We awoke to 43 degrees in our living room, the center of the house. Our pet bird was shivering. We camped out by the fireplace as much as possible, frantically running to plug in phones and turn on the oven as soon as we heard the refrigerator running. Freezing homeowners took dogs and kids to hotels if they had power — many did not —-others went to stay with friends or family. Thankfully, I had stocked up on food: grocery stores could not open without power.

Snowy view from our door

Candace Evans

More than 1.2 million North Texans were like us, without electricity for either long stretches or for days. The brutal winter storm —— 136 hours under 32 degrees —- brought a beautiful blanket of snow that actually stuck, but it also turned into a humanitarian crisis. Dozens of people have died of hypothermia or carbon monoxide poisoning, including an 11 year old little boy who died in his unheated mobile home in Conroe, near Houston. The storm froze 254 counties. On Tuesday, 60% of Houston households and businesses were without power. In fact, nearly 40% of the state was blacked out during this brutal winter storm.

No major city was spared. The city of Dallas quickly set up the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center as an emergency warming and sleeping central facility, with several more scattered across the city, including warming busses.

How could this happen in the most energy-rich state in the union?

We didn’t have enough electricity for our swelling population. And we have an unregulated market-oriented energy where companies compete against each other for consumer’s business. We have also kicked the can down the road when it came to updating grid infrastructure. One of my colleagues blames, besides our current governor, former governor Rick Perry, for failing to fix a busted system and keeping a cadre of pro-industry appointees on the Public Utility Commission state regulatory agency. As soon as the temperatures plummeted on Sunday night, folks cranked up the heat, creating a surge in demand for electricity (many Texas homes are heated by electric heat pumps) and natural gas. There was not enough to meet demand, so the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT, shut off power and initiated the rolling blackouts.

Oncor, for example, had to shed 36% of its electricity distribution in North Texas. We were one of them.

That was more than a third of Oncor’s coverage area. So the short rolling blackouts became much longer stretches. The blackouts were not uniform, however, because blackouts cannot take place in areas with hospitals, police or fire stations, which benefitted nearby homeowners. Talk about Location, location, location!

Oncor and all electric companies/providers in Texas take marching orders from ERCOT, whose senior director of systems operations, Dan Woodfin, says the providers were hamstrung and simply could not spread out the power cuts uniformly.

“Because of the amount of load shed that we’ve required in order to balance supply and demand, they really don’t have enough options to be able to rotate between different areas so they’re basically having to take all of the areas that don’t meet one of those critical or technical criteria,” Woodfin said. “They can’t rotate through them and still reduce the demand by the amount that we need that we need to maintain reliability.”

Indeed, we now hear that Texas’ entire electrical system was “seconds or minutes” from total collapse, or so Bill Magness, CEO of ERCOT said this week. A collapse that could have snapped out power for months.

“Our frequency went to a level that, if operators had not acted very rapidly … it could have very quickly changed,” said Magness.

My colleague also says ERCOT is bloated, Magess pulling in $883,000 annualy and “the people who work for Magness, of which 20 earned more than $200,000 a year with seven getting above $300,000, two earning over $400,000 and one making $500,000, according to nonprofit ERCOT’s 2018 federal tax filing. If you make that much to keep the lights on and fail, how can you sleep at night?”

Which is why on Sunday at 11 p.m. generation units started knocking off, and the lights went off about the time I got in the bathtub.

We have no idea if our pool will survive

Candace Evans

The disaster has become highly political, pitting green energy against fossil fuel, which still supplies 80% of our state’s energy. Governor Greg Abbott blamed our wind-turbine renewable energy (because of frozen wind turbines, that had not been winterized to save costs because it seldom gets this cold in Texas), but most of our energy comes from natural gas, nuclear and coal plants, which also froze up and quit operating.

Energy and policy experts agree that Texas’ decision to forgo equipment upgrades such as winterizing left the power system unprepared. It’s a challenge for energy markets to prepare for the possibility of extreme weather events that are unpredictable. Several Texas legislators have wanted to make changes: Sen. Bob Hall has introduced legislation trying to solve the grid’s vulnerabilities since 2015. He claims that upgrading and winterizing the grid costs far less than the subsidies spent on green energy.

Also true: Texas uses most power during the hot summer months for air conditioning; this winter storm was an anomaly.

Couldn’t we borrow energy from another grid? Because of a complicated, historical electrical utilities evolution, Texas has its own power grid —- with the exception of the El Paso region in far west Texas. This is, among other things, to avoid federal regulations that are said to add cost and burdens.

“Nuclear units, gas units, wind turbines, even solar, in different ways — the very cold weather and snow has impacted every type of generator,” said Dan Woodfin told The Texas Tribune.

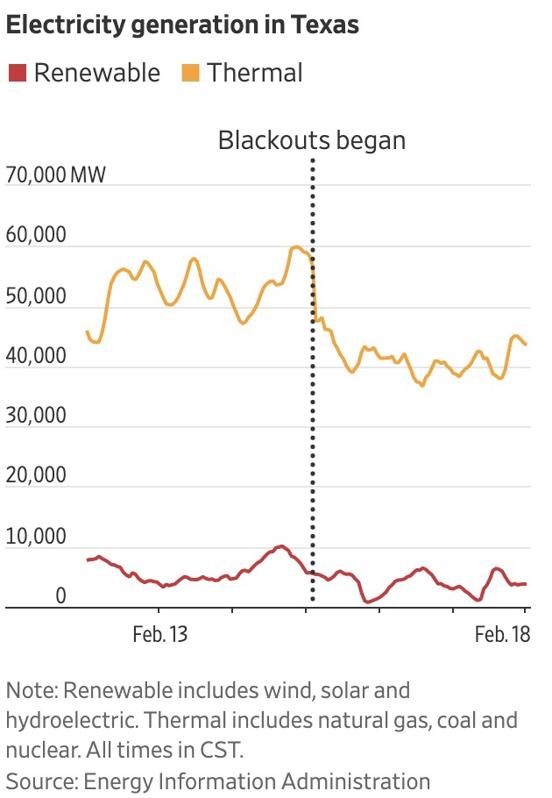

Electricity generation in Texas

Energy Information Administration

Consumer advocates, such as the former director of Public Citizen, an Austin-based consumer advocacy group, tried to push for changes after the massive ice storm that crippled the region during SuperBowl XLV at Cowboys Stadium February 6, 2011. Tom “Smitty” Smith, who is retired, told the Texas Tribune that rather than take regulatory action, the state handed out guidelines that were largely ignored. It is entirely possible to winterize all the power plants and wind turbines, it just takes money, he says. And consumer advocates like Smith say the Texas energy providers are businesses more interested in profits.

But ERCOT officials said that new winter practices were input after the 2011 freeze, and new voluntary “best practices” were adopted. During recent storms, it appeared that those efforts worked. But this storm was even more extreme than regulators or anyone anticipated, even when based on the 2011 storm models. Dan Woodfin acknowledged any changes made were “not sufficient to keep these generators online,” during this brutal storm.

William Hogan, an energy economist at Harvard University who helped design the Texas electricity market, told the Wall Street Journal “this week’s blackouts weren’t indicative of a major design flaw, but rather inevitable imperfections stemming from extraordinary weather challenges.

“I don’t know of any market design that exists anywhere that would have anticipated and have been prepared for something of this scope and scale,” he said.

The question is: do you invest money in infrastructure that may be overkill for a once-in-72-years weather event, or do you play the odds? Better to ask when everyone is warm and their houses are repaired.

By today, most of us have electricity. There are an estimated 20,000 in Dallas and Fort Worth still without power. The problem now is water, both from distribution and damage perspective.

That Crack I Heard Was An Attic Water Pipe

As structures warm, frozen PVC or copper water pipes burst from the cold and pressure, resulting in leaks. So do utility main water lines, which is why 22 North Texas municipalities are being told to boil water — or getting bottled water from relief organizations. A reported 14 million Texans are without potable water.

My executive editor has had power the entire week: her neighbors, who didn’t, have had to shut off the water to their homes to prevent damage. Jo’s house has thus become the neighborhood watering spot. People are graciously letting neighbors shower, bathe and warm up.

Volunteers hand out cases of water bottles to Galveston residence at the Schlitterbahn Waterpark … [+]

AFP via Getty Images

I was able to unfreeze my laundry line with a heater, hairdryer and pouring boiling water down the laundry drain. I’m in line for a plumber to repair the hot water heater, replace the burst pipes, then fix the damaged ceiling. He tells me the storm will delay all building as contractors are pulled from construction to repair homes and apartments. Those of us who grew up in colder climates wonder why some Texas homes, generally built for warm weather, are persnickety in extreme cold weather, kind of like our electric grid. We once owned a 60 year old home here. In winter windows froze and sweat, and the house was freezing when the mercury dipped.

“Older houses are colder because of two big reasons: warm air wants to get out, cold air wants in,” says John Hawkins, CEO of Dallas-based Hawkins-Welwood Homes. “Warm air rises and most older homes are poorly insulated in walls, attics and ceilings. Cold air comes in through uninsulated floors and poorly insulated windows. Double pane, insulated windows prevent both heat and cold transfer in your home.”

Well-insulated homes, says Hawkins, can withstand temperature dips even to the sub-zeros. Most Dallas homes are ether pier and beam or build on post tension slabs, which I think makes them colder.

“Basements that our grandparents had were built in a time when labor was very cheap,” he says Hawkins. “Many homes in northern states had basements because they were easier to keep warm than an attic. In Dallas, we tend to have a higher water table. Today when we build a basement in Dallas, we go to great expense to waterproof it.”

Building a basement, says Hawkins, costs two to three times as much as a pier and beam foundation.

icy alley

Candace Evans

My neighbors have ceilings caving from burst pipes. The fire sprinkler went off in a $6 million University Park home, ruining everything. Another’s back guest house filled with water, which poured down the alley creating a skating rink. Another had a generator, which failed to work. Even the toney Dallas Country Club, recently refurbished, suffered extreme water damage.

The final cost: this will likely be the most expensive storm in Texas history, even more expensive than Hurricane Harvey at $20 billion in insurance claims. It could even be the most expensive storm in U.S. history, dwarfing a 1993 winter storm that cost $5 billion. In Texas, giant claims usually come from hurricanes and tropical storms on the coast, until, that is, Mother Nature graced us all with -2 degree weather as recorded at DFW Airport, the lowest temperature in the region in 72 years.