The Constitution says states can’t impair contracts. But it’s OK to impair some contracts if there’s … [+]

RANJAN SAMARAKONE

“[N]o State shall … pass any … Law impairing the Obligations of Contracts.” That prohibition appears in Article 1, Section 10, of the United States Constitution. It sounds simple, straightforward, and absolute. Clearly, states and hence the municipalities within them have no power to pass laws that impair contracts.

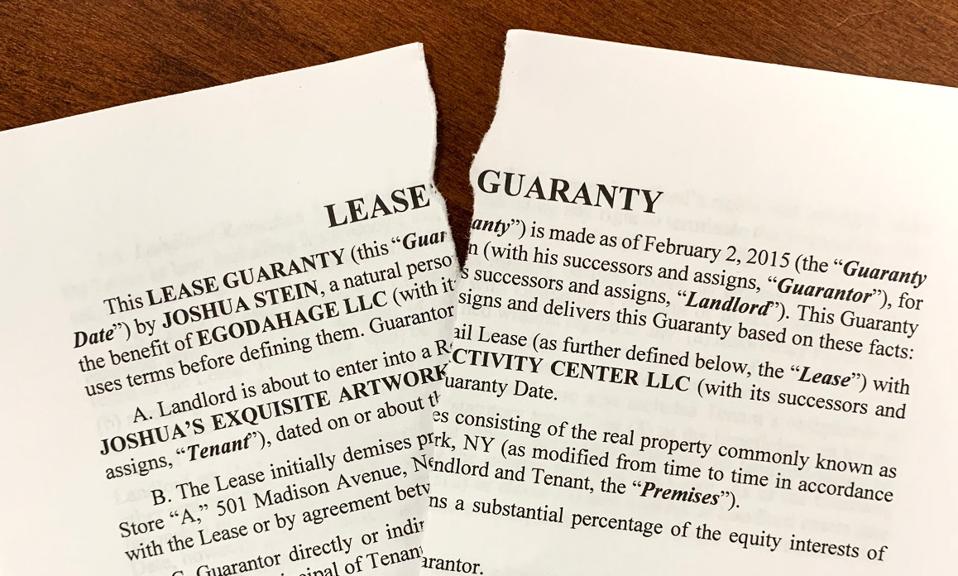

Does that constitutional prohibition actually mean what it says? Does it prevent the New York City Council from passing a law that prevents property owners from enforcing guaranties of leases? Does it invalidate, for example, a law that permanently excuses some guarantors from some of their obligations under guaranties?

No, no, and no.

That’s all according to a federal district court decision issued in late November, which upheld New York City’s law prohibiting property owners from enforcing certain lease guaranties. (Melendez v City of New York, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, No. 20-CV-5301 (RA).) As interpreted by the court, the prohibition permanently wipes out guarantors’ liability under the guaranty contracts they signed, at least for liability accruing through March 2021.

An ordinary reading of the words “impair” and “contract” would suggest that the City’s law violates the Constitution. But the courts have a way around that, according to last month’s decision.

State and city governments have the right to exercise the “police power,” meaning the power to “safeguard the vital interests” of their citizens. Previous Supreme Court decisions have apparently concluded that the police power is more important than contracts. So the City Council can impair contracts if that serves some vital interest.

The courts go a step further, traditionally exercising great deference to legislative decisions implicating the police power. If a legislative body acts in good faith to serve the public interest, even by interfering with private contracts, courts will hesitate to interfere.

MORE FOR YOU

If, however, a legislative body substantially interferes with a contract (which the court agreed happened here), a court will scrutinize that interference, and insist that the law must advance a legitimate public interest and must be reasonable and necessary to do so.

Applying that standard of scrutiny, the district court concluded that the City’s guaranty law does serve a legitimate public interest, as opposed to some special interest or municipal interest of the City itself. It is in the public interest – or at least the City Council could legally decide it is in the public interest – that owners of small businesses hurt by the Covid pandemic not face financial ruin because of guaranties they signed.

Is the guaranty law “reasonable and necessary” to serve that public interest? The court said this was the “closest question” at issue in the litigation. Again, the court resolved it by being “extremely deferential” to legislative decisions that seek to advance a legitimate public interest. So of course the court concluded that the guaranty law was “reasonable and necessary.” It was up to the City Council to decide whether to require property owners or their tenants and guarantors to suffer the financial pain from the pandemic. The courts should defer to whatever the City Council decides.

Tomorrow perhaps the City Council will, in its wisdom, decide to wipe out all the credit card bills owed by all the City’s small business owners affected by Covid. Why not? Presumably the district court would sustain that, too, based on the great deference it gives to the City Council.

The district court’s validation of the City law took comfort from the fact that the City Council tailored its guaranty law to respond to the Covid pandemic. The law applies only to certain leases that were directly affected by closure orders. It applies only to individual guarantors, not big bad corporate guarantors. It permanently wipes out only guarantors’ obligations arising in a period ending in March 2021 – not all obligations of those guarantors for all time.

Finally, in a comment that sounds like a cruel joke to any property owner familiar with small business leases and lease enforcement, the court declared that the law: “leaves commercial landlords with other means through which they can recoup the rental income they have lost. Here, for instance, [a property owner] remains free to attempt to recover unpaid rent and interest from tenants, charge late payment fees, terminate the tenant’s right to possession, evict the tenant, and recover damages.”

If all those other rights and remedies were reliable and quick, property owners wouldn’t ask for guaranties. They ask for guaranties – and typically won’t sign small business leases without guaranties – precisely because they know their rights and remedies against small business tenants aren’t worth much and will take forever to enforce, especially in New York. That would be true even without the various moratoriums in effect these days.

By depriving property owners of the benefit of the guaranties they demanded as a condition to signing leases, the City’s guaranty law isn’t just making a minor tweak to a business relationship. Instead, the law completely changes the business relationship into one that the property owner never would have undertaken voluntarily – in practice, free occupancy of the owner’s building for an extended time.

So much for the constitutional prohibition on impairment of contracts. It’s OK to impair contracts if the Legislature has a decent reason and the impairment is reasonable and necessary—and the courts won’t ask too many questions. With luck, this litigation will make it to the Supreme Court, which might take a different view.