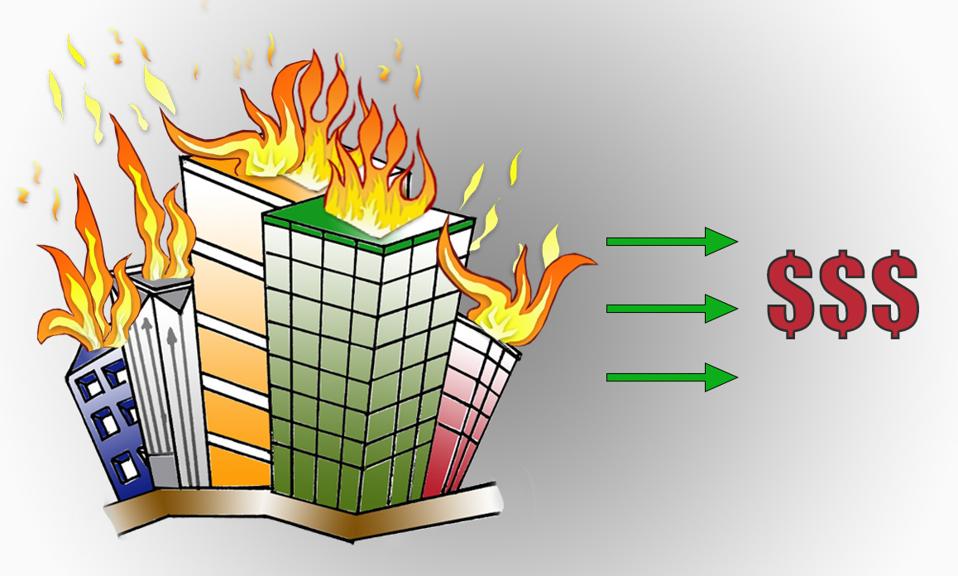

When a leased building burns down, the tenant’s lender may try to take the insurance proceeds and … [+]

RANJAN SAMARAKONE

Over the life of any lease, the property owner may obtain mortgage financing, or even sell its position, several times. If the lease is a ground lease, the tenant will probably also do the same. Each of those transactions involves a lender. Each lender wants comfort about the status of the lease.

Nearly every lease therefore requires each party to sign so-called estoppel certificates for the other party’s lender. Those certificates confirm facts about the lease, such as the lack of defaults, the current rent if it can’t be determined from the face of the lease, and whether any required construction was completed. In the case of a ground lease, the property owner may also commit to sign an agreement with the tenant’s lender to confirm the lender protections in the lease.

These certificates and agreements should create absolutely no controversy or commentary at all. But they often do. That’s because lenders often use them as opportunities to do more than reconfirm facts or previously existing terms of the lease. Instead, as one unfortunately very common example, a ground lease tenant’s lender might ask the property owner to agree, in an estoppel certificate, that the provisions of the loan documents on insurance proceeds and restoration will supersede any inconsistent provisions in the lease. In other words, if the building burns down, then the lender wants the right to take the insurance proceeds even if the lease said they had to be used to restore the building.

In one recent transaction the author handled, the tenant’s lender wanted the property owner to agree in an estoppel certificate to (among other things) expand the scope of permitted leasehold lenders; refrain from taking certain actions otherwise permissible in a tenant bankruptcy proceeding; and waive some claims that the property owner could otherwise have asserted against the lender if it ever foreclosed. The property owner, not in an accommodating mood, refused. The tenant blamed the property owner when the tenant’s financing collapsed.

A recent federal case in Massachusetts considered a similar sequence of events. There the lease required the property owner to enter into an agreement with the tenant’s lender “agreeing to all of the provisions in this Section,” i.e., the section of the lease that gave the lender certain protections and rights.

MORE FOR YOU

The lease said any insurance proceeds had to be used to restore the building. But the lender, as so often happens, wanted the property owner to agree that the provisions in the loan documents on insurance proceeds would supersede anything inconsistent with the lease. And of course the loan documents said the lender could keep the insurance money so the building wouldn’t be restored.

The property owner said no, instead insisting that any inconsistency had to be resolved in favor of the lease. The parties went back and forth but neither the property owner nor the tenant’s lender relented. Ultimately the deadline to close the loan passed. The tenant lost its lender and sued the property owner.

The court concluded that the property owner had no obligation to sign an agreement that gave the lender rights beyond those the lease already provided. Since the lease required insurance proceeds to be used to restore, the property owner had no obligation to agree the lender could keep them. Thus the property owner did not breach the lease, the tenant lost the litigation, and the tenant had to pay the property owner’s legal fees.

The case reaffirms the rather obvious proposition that when a lease requires a property owner to confirm facts in an estoppel certificate or to confirm in a separate agreement a lender’s rights and protections under the lease, the property owner has no obligation to do anything more or to change anything in the lease. That was comforting, as it confirmed the position the author’s client took in the matter described above.

Conversely, a careful tenant won’t allow itself to be placed in a position where its financing depends on the property owner’s willingness to vary from what the lease requires. Instead, the tenant will ask its lender to confirm, early in the closing process, that the lender approves the lease exactly as is, and won’t ask for anything more than exactly what the lease requires the property owner to deliver.