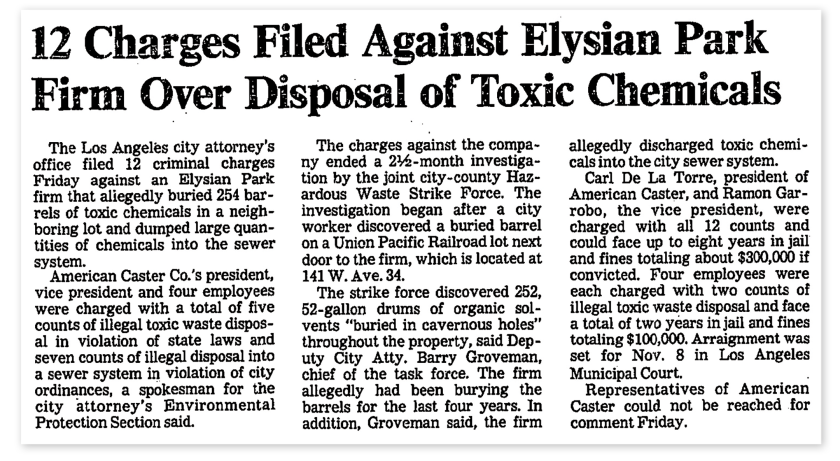

In the summer of 1984, investigators peered into a cave dug beneath the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles and found dozens of rusted 55-gallon barrels filled with toxic chemicals.

Some of the barrels lay nearly empty after their contents had leaked through corroded metal and escaped into the soil.

“I saw the hole and I said, ‘I can’t believe it — who would do something like this?’,’’ recalled Barry Groveman, the head of the now-defunct Los Angeles Hazardous Waste Task Force. At the time, he described the dump as “a violent crime against the community.”

Groveman and his investigators went on to uncover 252 barrels buried in similar caverns surrounding a manufacturing warehouse at 141 West Avenue 34, where the American Caster Corp. operated. Some of the chemicals were also dumped into sewer lines. Before the discovery, the dumping practice had carried on for four years.

After a hasty cleanup, and as the company’s executives and several employees served six months in jail and paid thousands of dollars in fines, investigators moved on to other cases. The court records were eventually destroyed — common for old municipal documents — and the case largely faded from memory.

Now, nearly 40 years later, environmental concerns at the Avenue 34 site have once again shaken the neighborhood as real estate developers want to demolish the industrial warehouse and, in its place, build a five-story apartment complex, retail space and an underground parking garage.

Lourdes Garcia and her 8-year-old son, Enzio Parra, on their way to Hillside Elementary School. At an abandoned industrial warehouse on Avenue 34, a developer wants to build a five-story apartment complex.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Until recently, community activists had opposed the project because they said it would gentrify their predominantly working-class, Latino and Asian neighborhood. They also worried that contamination from a neighboring dry cleaner could be disturbed during construction and leave them vulnerable to exposure.

While regulators deemed the former dry cleaner site to be unfit for residential development, due to lingering chemicals beneath the surface, the state allowed developers to build housing on the neighboring Avenue 34 site.

But when a community member recently came across archived Los Angeles Times articles highlighting the 1984 case, the revelation shocked residents. They are now accusing California regulators of failing to properly test the decades-old dumpsite and surrounding properties, and are calling for a new cleanup plan.

In December 2021, Sara Clendening, president of the Lincoln Heights Neighborhood Council, dug up this Los Angeles Times article from 1984, revealing a hidden layer of the Avenue 34 development site’s history. (Click image above to view a pdf.)

Neighborhood activists Patricia Camacho and Michael Hayden, who both live across the street from the proposed housing development, worry that illegally dumped chemicals may have migrated to other areas.

“Toxins don’t stop at property lines,” Camacho said. “It’s just so disappointing that the cleanup plan didn’t include testing outside of the property. Those of us who live 30 feet from where this is happening, we feel like we aren’t being protected.”

When project developer R Cap Avenue 34, LLC sought approval from the city and state to build in 2020, the group insisted the Avenue 34 site had little to no contamination and chemicals were confined to the dry cleaning site.

A school bus on Pasadena Avenue in a neighborhood where a developer wants to build a five-story apartment complex on what is currently an abandoned industrial warehouse.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

However, testing done at the property in late 2021 revealed levels of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, that were more than 4,000 times higher than what is recommended for residential standards. The compounds included the dry cleaning solvent tetrachloroethylene, or PCE, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says may harm the nervous system, reproductive system, liver and kidneys, and may possibly cause cancer.

Despite community protests, reignited by discovery of the 1984 case, the developer’s plan to remove chemical waste from the site was approved by the state’s Department of Toxic Substances Control, which has overseen cleanup at the laundry site. The agency declared that “nearby residents, businesses, and schools are safe from contaminants found at the Site,” and in its determination, added that “there is no significant risk beyond the property boundaries.”

The department said the 1984 case has no impact on the cleanup of the site.

“Most responsible parties want to make sure once they develop a property there won’t be lingering concerns or exposure that could harm future residents, or people nearby — that’s not the case here,” said Angelo Bellomo, former head of environmental health for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and a former DTSC official who has been critical of the project’s cleanup plan. “How could this get support from city council, local regulatory agencies and the state regulatory agency?”

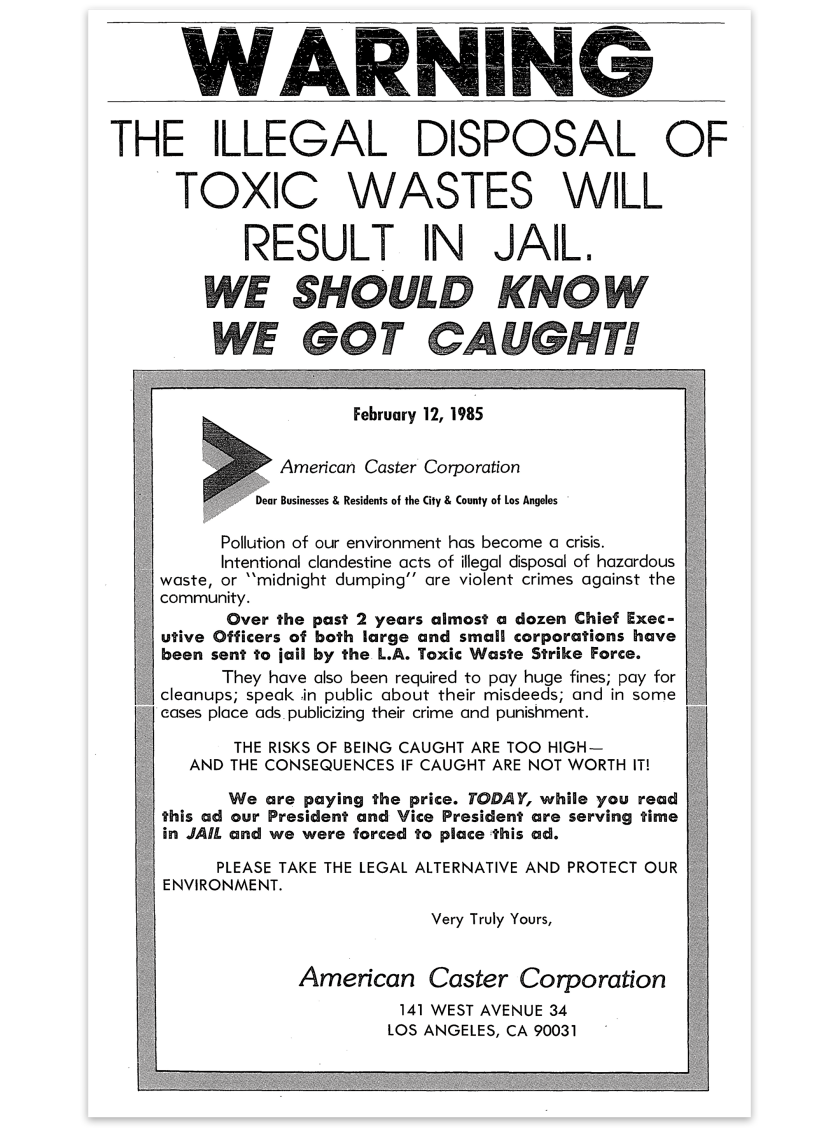

The American Caster Corp., which operated at the Avenue 34 site, was forced to buy a full-page advertisement in the L.A. Times after being convicted of burying and dumping toxic waste in Lincoln Heights. “The entire purpose of it was deterrence,” said Barry Groveman, an attorney who prosecuted the 1984 case. (Click image above to view a pdf.)

Today, hulking and abandoned warehouses span most of the development site. Feather reed grass and weeds sprout from cracked asphalt and obscure walls. DTSC work notices announcing last year’s testing are zip-tied to fences, while an abandoned security patrol car with a toppled office chair on its roof sits beside a large pile of sandbags and metal barrels.

“I spent every day in 2012 and 2013 on that site, and we had no idea it was contaminated and poisonous,” said Fernanda Sanchez, who in high school took kickboxing lessons at a gym that once operated at Avenue 34.

Born and raised in Lincoln Heights, she joined efforts in 2020 to inform her neighbors of the new development, which along with the threat of contamination, she feared would drive up property values and price out current residents. Last year, she was elected to the neighborhood council.

“It’s just a form of environmental racism,” Sanchez said. “Our low-income, immigrant communities are not seen as valuable, whether it’s displacing us or poisoning us — they completely disregard our human rights.”

Developers hope to transform the abandoned property into “a healthy and vibrant community” with public open space within walking distance to two Metro Gold Line stations. The project promises 468 apartment units, most at market rate, with a small portion, 66 units, set aside as affordable housing.

“We will shortly begin the process of a site cleanup that was approved by and will be carried out under the supervision of the State Department of Toxic Substances Control,” the development group said in a statement. “As was always required by the Avenue 34 project’s entitlement approvals from the City of Los Angeles, the site has undergone extensive environmental review, analysis, and testing.”

Parents drop their children off at Hillside Elementary, located on Avenue 35, very close to an abandoned industrial site on 141 W. Avenue 34 in Lincoln Heights.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

The demolition of warehouse buildings and the cleanup of soils is scheduled to begin in early May and will continue for several months.

Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics, who has voiced concerns about the project since last year, also questioned why the state didn’t conduct more testing after the community discovered the 1984 case.

Williams and others say they are worried about the presence of VOCs in soils beneath the development site. These often odorless compounds may enter buildings through cracks, windows or utility lines in a phenomenon known as vapor intrusion.

To protect against vapor intrusion, experts are trained to track how far chemicals have traveled beneath the ground before removing them from the soil.

“We always look very carefully at a site that’s getting developed and ask, ‘Are we protecting against this phenomenon of vapor intrusion?’” said James Wells, an environmental geologist who was an advisor to the state during its cleanup of the Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon and has recently been advising Lincoln Heights residents. “At this site, I didn’t feel like the [cleanup plan] met that standard.”

State regulators continue to assure the community that dangerous chemicals on the property have not spread to nearby homes.

Wells, however, said such a conclusion was premature, given the rediscovery of the 1984 chemical dump.

Wells and Bellomo are calling on regulators and developers to pause demolition and conduct more testing. They also want regulators to conduct a full investigation into the nature of the illegal dumping as well as how the chemicals were cleaned up.

Exactly how deep DTSC looked into the 1984 case before approving the developer’s cleanup plan remains unclear. However, Groveman, the head prosecutor in the 1984 case, said DTSC contacted and interviewed him in early April, which was several weeks after the department had already adopted the cleanup plan.

In the days since then, DTSC confirmed that it has looked at county and state records and could not find any documents that show the location of the buried barrels or how they were cleaned up.

Neither the cleanup plan nor DTSC’s summary in the state’s Envirostor database — an online source where officials store records of contaminated properties — make any mention of the 1984 case.

“This is a massive area of uncertainty. How could we not want to fill that gap of uncertainty, given that this is a sort of notorious site back in the ‘80s,” Wells said. “The cleanup standards were nothing like they were today.”

Javier Hinojosa, a DTSC official who is working on the testing and cleanup at Avenue 34, said he agrees cleanup standards were not what they were 40 years ago. However, he stood by the department’s testing at the site, which also looked for the chemicals discovered in the 1980s case.

“There should be some confidence in the data and that we’re going to do the cleanup,” Hinojosa said.

A metal gate blocks the entrance to a complex of an abandoned industrial warehouse.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

It remains to be seen whether the newly revived concerns about the 1984 dumping case will delay development of the site. However, even in December, public officials like Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis and U.S. Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Los Angeles) have said approval of the cleanup plan was premature and more testing should be done. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has also met with DTSC officials in December and expressed concern that their testing standards were less stringent than federally-recommended standards for residential developments.

In the meantime, longtime residents like Cesar Salazar, 72, said the pace of development in northeast Los Angeles was increasing.

Salazar recalled a string of developments that resulted in the eviction of residents to make way for new housing projects. However, he said he was surprised to learn of the latest project, given the site’s history of toxic waste.

Salazar remembered decades ago in the 1980s, watching bulldozers bore trenches into the soil near warehouses on Avenue 34 and as workers hauled canisters of chemicals, tossing them into the holes like coffins of a mass grave. The smell, he recalled, was foul, similar to the stink of car grease.

“I was very surprised they were so daring and blatant,” Salazar said. “They didn’t even wait for the sun to go down.”