This has been a period like no other in the past century. We will have to wait through the third … [+]

Getty

Sometime around the beginning of March, the world as we knew it changed. It didn’t happen all at once. Stealthily, the impact of the coronavirus crept into every nook and cranny of our lives, where it remains today and for who knows how long. In New York City, the infection and death rates have now peaked and dropped, so agents are once again, as of June 22nd, permitted to show real estate, with all the proper precautions. The five boroughs are the last places in the country to re-open to real estate showings, thus allowing a market, shut down almost completely to new transactions for three and a half months, to develop.

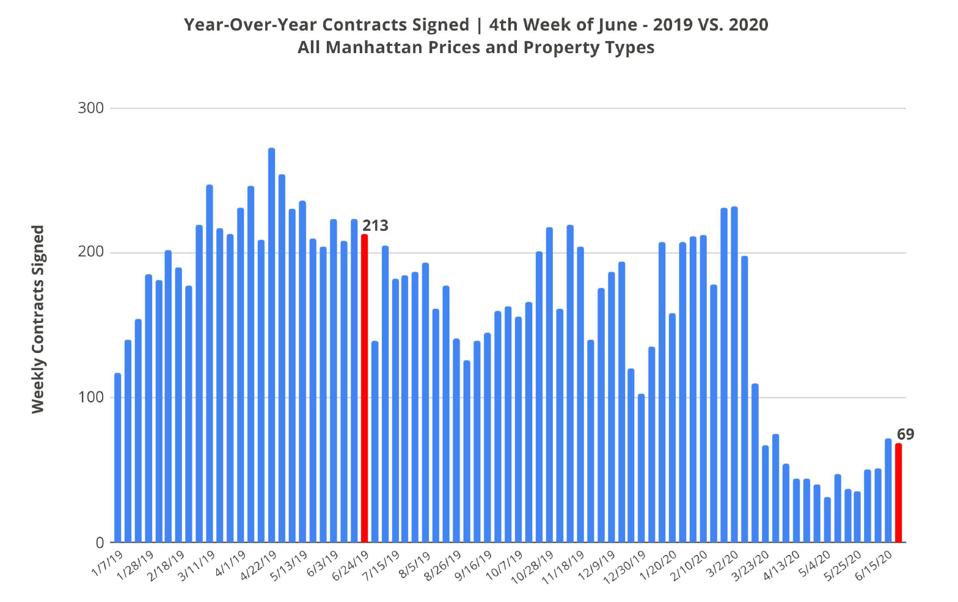

The two red bars represent the two year-over-year values for contracts signed the 4th week of June, … [+]

UrbanDigs

According to a recent UrbanDigs report, Manhattan properties in contract were down 68% year-over-year for the fourth week of June (213 in 2019 vs. 69 in 2020), and that number still reflects properties which were signed before the pandemic shut business down. For properties above $10 million, deals in contract tell the same story with a 67% decline year-over-year for the fourth week of June (3 in 2019 vs. 1 in 2020). So it’s almost impossible to write about the market during the second quarter; there barely was a market. But I can write about what we have learned, especially as we now look back on this unprecedented period in the life of our city and our country.

- You have to see it in real life. No matter how detailed the description, no matter how well filmed the video, few people want to rent or purchase a home in which they have not set foot. While there were deals made virtually, they were few and far between, and almost always involved special circumstances: the buyer knew the building from before, or it was a new development with an extensive online gallery with storyboards of the finishes and fixtures. Even the best online experience cannot replace the touch and feel of the property when the buyer walks in the door.

- One crisis is not like another. Throughout the early months of the stay-at-home order, economists, real estate agents, and finance gurus all tried to analogize the impact of the pandemic to that of the 2008 recession, or 9/11, or even the recession of 1988. As it turned out, none were similar enough, either to one another or to the current pandemic, to enable the construction of a credible analogy. It’s true that 9/11 created paralyzing fear in people, and many left New York. But it only happened once, and after a few months, most of those who left came back. The city mourned, but people continued to go out for dinner, to movies, to the theater. Same with the big recession, which, like the coronavirus, was invisible but highly destabilizing. People continued to go out. In this situation, the social basis of people’s lives has been undercut. Months without socializing, without restaurants, without movies or plays or baseball or opera, have left city dwellers disoriented. Do they want to move to the suburbs? Is it actually safer there? Or, if they do leave town, is it reactive and will they too return to New York as all the wonderful things about the city come back to life?

- Our homes are our castles. Never have New York City dwellers logged so much time at home. Every urbanite knows the doorknobs, creaking floorboards, and wall imperfections of her home like never before. Has this made them want to move more, or less? Does this make them yearn for more space? Different space? A house with a yard? Greater proximity to the office? We will have to wait to learn how homebuyers’ preferences and priorities may have changed as a result of being home so much.

- We can work remotely (but do we want to?). Perhaps the most interesting takeaway of all. In this era of e-mail, text, 24-hour smartphone news bulletins, and Zoom, we can do almost anything from home. But after three and a half months, many long to return to the office. It turns out that work/life balance may be easier to achieve when the different activities are not taking place under the same roof.

Every New Yorker has learned a great deal about space during the pandemic. Enclosed within the spaces in which we live, often barred from the spaces where we work (unless we were essential, and sometimes even then) our relationship to the real estate we use and inhabit has never been outlined in starker relief. This has been a period like no other in the past century. We will have to wait through the third quarter to see its actual ongoing impact on residential, retail, and commercial prices, but one thing seems certain. How we use the built spaces around us will never be quite the same again.