Does the typical appraisal protect you from overpaying for a house? If it doesn’t, what would that mean for house prices in general?

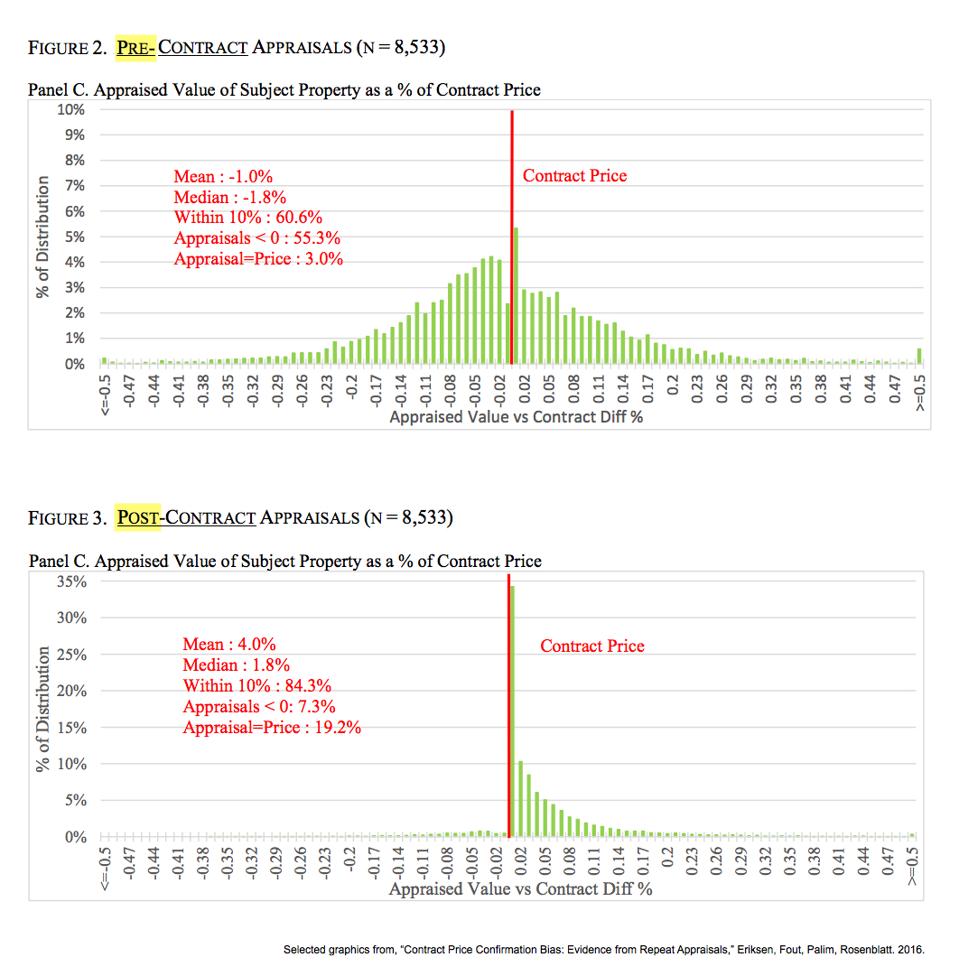

A study looked at a particular set of 8,533 houses that Fannie Mae foreclosed on from 2012 to 2015 and where two appraisals were done on each house. The first appraisals were done right after Fannie took ownership and the second appraisals were done after the houses went under contract to buyers. The second appraisals were the typical lender’s/bank appraisals that are ordered by your mortgage company when you’re in the process of buying a house.

The first and second appraisals were done within six months of each other and no alterations or repairs were made to the houses between the two appraisals. The biggest difference wasn’t the house. The biggest difference in the second appraisal was the appraisers knew what the agreed-upon sales prices were in the sales contracts.

Did knowing the agreed-upon sales prices in the written sales contracts affect how the appraisers appraised the values of the houses? Yes. It did. A lot.

On average, the second appraisals were 4% higher than the first appraisals.

Pre-Contract vs Post-Contract Appraisals

Source: “Contract Price Confirmation Bias: Evidence From Repeat Appraisals,” Eriksen, Fout, Palim and Rosenblatt, 2016. Annotations: John Wake.

In addition, about half of the first appraisals came in below the eventual sales prices in the contracts but only 7% of the second appraisals come in below the prices in the contracts. They call this phenomenon “appraisal bias” or “confirmation bias.” There’s a strong bias for appraisals to come in at, or above, the sales prices in sales contracts.

Here’s part of the problem. Houses have a fair market value price range, not a fair market value price down to the dollar. House appraisals, however, have to be down to a single dollar amount. If a lender’s appraisal comes in lower than the contract price, by even $1, it causes a ton of extra work for the mortgage company (that hired the appraiser) and can be a huge problem for the buyer and seller.

Lender’s appraisals are usually done late in the sales process which makes the disruption caused by appraisals below the agreed-upon sales prices far worse. Sellers may have already moved out. Buyers may have already sold their houses or canceled their current leases. Because of that, appraisers rarely come in with appraised values that are just below the agreed-upon prices in the contracts.

But what about 1% below the price in the contract? Is the appraiser so confident of the value of the house that they know the house is absolutely, positively not within 1% of the price in the contract? How about 2%, 3%, or 4%? The average appraised value of the houses in the study was 4% higher when the appraisers knew the sales prices in the contracts.

One of my conclusions from the study is that your lender’s appraisal will protect you from paying WAY too much for your house but it won’t protect you from paying a few percentage points too much for your house.

Appraisal Price Creep

Now let’s talk about what this bias toward high appraisals — and high house sale prices — does in the long run to house prices, household debt, wealth inequality, income growth, and economic growth.

The paper makes an extremely convincing argument that appraisal confirmation bias exists but it doesn’t go the next obvious step. It doesn’t discuss the macroeconomic impact of having an upward bias on the general level of house prices.

Let’s say an appraisal comes in 4% too high as would seem common from the study. That 4%-too-high, appraisal-approved house sale price might then become a comp (comparable property) for the next appraiser to use when appraising the value of another house. Then that house might become a comp for a third, and so on. If each of these sales is a little too high due to appraisal bias, house prices would naturally tend to slowly ratchet up. It’s hard-coded into the system.

Even if the market fundamentals aren’t pushing up house prices, this appraisal price creep, all on its own, would tend to cause house prices to rise. If market fundamentals were pushing up house prices, this appraisal creep would tend to push them up even more.

It’s a bug in the modern house buying and selling system that continually pushes house prices higher than they would otherwise be (although, others might see it as a feature).

In the olden days, the U.S. mortgage system was dominated by a zillion small, local savings and loans. Those S&Ls made the mortgages, held them on their own books, collected the mortgage payments and dealt with late payments and foreclosures, all themselves. They might use their own in-house appraiser. Since they usually kept the mortgages they made, they really didn’t want overpriced mortgages on their books during any future real estate downturn. The S&Ls took all the downside risk.

In the 1990s the U.S. mortgage system for single-family houses became dominated by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In time, the two government-sponsored companies became so large that if they were one company, they would have been the largest bank on the planet.

Fannie and Freddie set the rules for the mortgages they would buy (and then resell), including the appraisal rules. This appraisal system prevented them from buying mortgages on houses that were way overpriced even if it didn’t prevent them from making mortgages on houses that were a few percentage points overpriced. Apparently, they were okay buying mortgages on overpriced houses as long as they weren’t too overpriced. Perhaps the logic was, ‘Why kill the sale of a mortgage on a house that was a little overpriced when house prices are increasing so fast? It’s safe enough.’ Well, as long as house prices were increasing they were safe enough.

Later on, we learned that Fannie and Freddie’s lending standards weren’t safe enough in a lot of different ways. They’ve now been in conservatorship for over a decade.

Economic Impact of Appraisal Creep

What if there were a way to prevent this self-reinforcing creep in house prices caused by the modern mortgage system? What would happen?

If house prices didn’t increase so fast it would eventually be bad for the financial sector, they would make less money from mortgage interest. (For many years, more than half of each monthly mortgage payment goes just to pay interest for that month.)

But what about families? If households had smaller mortgage payments than otherwise, what would they do with that money? They’d spend most of it.

A lot of it would go toward buying things that create jobs. Smaller house price increases would eventually mean more money going toward buying things that create jobs, income, and economic growth.

And house prices that don’t increase as fast would tend to improve wealth equality in at least three different ways, 1) by increasing jobs and income growth (see above), 2) by increasing homeownership, and 3) by increasing the long-term wealth creation of homeownership. More stable house prices increase the long-term wealth created by owning your own house. Fewer and smaller real estate booms and busts mean fewer lower-income and newer homeowners are wiped out financially by real estate downturns and busts.

And what they didn’t spend from those smaller mortgage payments would be saved, further increasing household financial stability.

Next Steps

That’s the hypothesis. Appraisal creep exists, it makes houses more expensive than they should be and that’s a drag on the economy.

Now we just need to figure out how to stop appraisal creep and all the other parts of the modern mortgage system that somehow evolved into unnecessarily increasing house prices and household financial instability over the long term.

Don’t Tell The Appraiser the Contract Price

The Fannie Mae paper above suggests as a possibility, among other things, not giving appraisers any information about the sales prices agreed upon in sales contracts. If that could be enforced, it would theoretically stop appraisal price creep.

Buyers Order Appraisals Early

In addition, following a suggestion from the Mortgage Professor, I would suggest that buyers do their own appraisals early. Right now, however, if a buyer gets their own appraisal done early on to help with price negotiations, Fannie, Freddie and the rest will usually still require the lender to get a lender’s appraisal done and the lender will charge the buyer for it.

Buyers don’t want to pay for two appraisals. That’s why buyers don’t often get their own appraisals done even though appraisals are most valuable to buyers early on in the process when they’re still negotiating price with the seller.

Instead of working for the lender late in the process, the appraiser could be working for the buyer early in the process which would help buyers negotiate the price and reduce appraisal creep.

We could help stabilize house price increases and maximize household wealth creation over the long term in a lot of different ways, including these two ways.