Ever driven around the vastness of Greater Los Angeles and seen the freeway offramp for the town of Gladysta? Or Terracina? How about the San Gabriel River town of Chicago Park — literally in the San Gabriel River?

If you saw them, you might not have passed a Breathalyzer test. Those towns never existed.

The county of Los Angeles embraces more than 4,000 square miles. Within those miles are now 88 incorporated cities, Los Angeles chief among them. But here’s a vanishing act for you: There were once at least 100 towns laid out here, all ready to welcome the big wave of settlers from points east who created the region’s big real estate boom just over a century after the city was founded in 1781.

Some were actual burgs that grew and dwindled, were annexed or swallowed up. Some were “dream towns” imagined by real estate developers, planned and platted and sold, but never born. Bearing some fanciful names like Ivanhoe and Wahoo, some were sold off with hopes and prices higher than their survival odds. Others were peddled almost as cynically as Florida swamplands: “ocean view” cities nearly 30 miles from the ocean, and other “view” towns whose vistas were desert desolation.

Between 1884 and 1888, real estate sold like mad, sometimes to newcomers who often went from train station to hotel to real estate auction. But the bubble collapsed, and within a year or two, 60 L.A. County towns had vanished.

Poof.

One town had a single forlorn resident hanging in. The developers’ white stakes marking boundaries of defunct towns were as mocking as tombstones.

Phantom cities fall broadly into two types, the once-were and never-were.

The once-were were bona fide townships and incorporated cities that became suburbs within the city of L.A. Eagle Rock, after 11 years as a city, became part of L.A. in 1923. Hollywood lasted as a city for just seven years before joining up with L.A. The way it was described in “La Reina,” a 1929 promotional history of L.A., “Struggling for an adequate water supply, Hollywood came into [L.A.] in 1910.” A water supply, more than any other consideration, made cities fold their hands and join hands with L.A., the lord of waters.

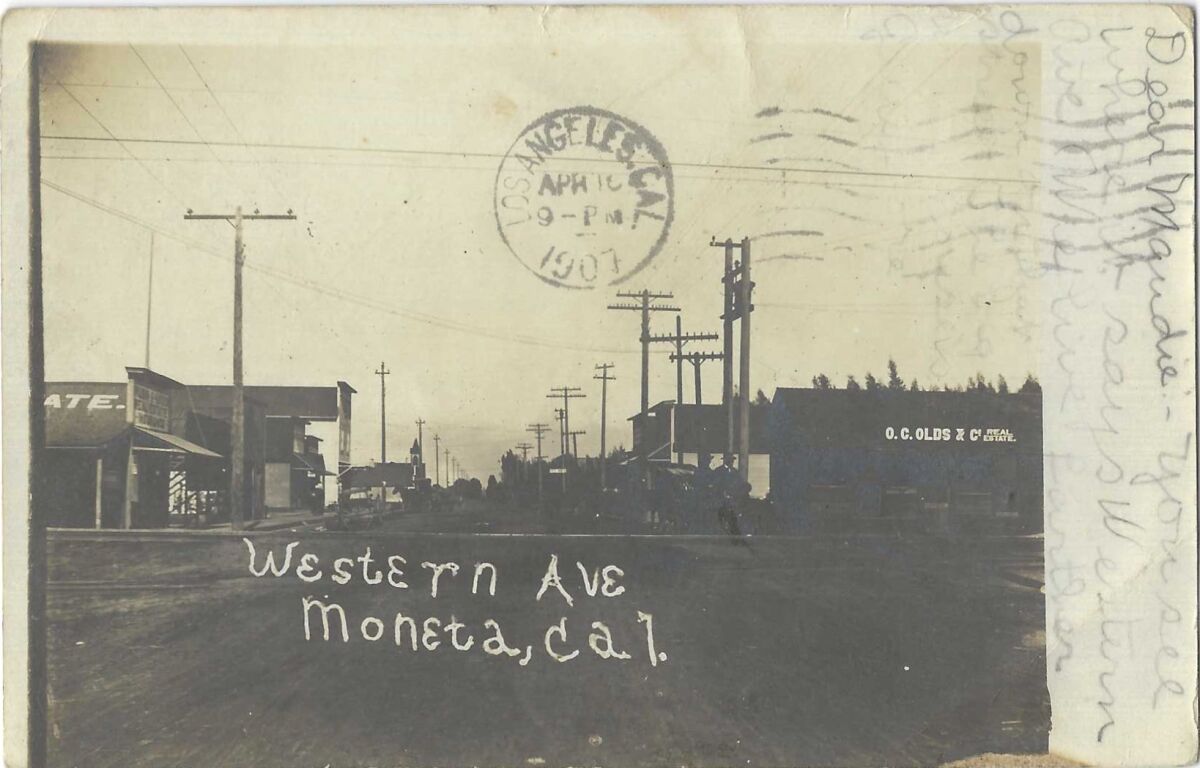

A rare 1907-postmarked postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection shows Western Avenue in what was then Moneta. Today it’s part of Gardena.

Moneta was a township, now part of Gardena, that flourished from the turn of the century until World War II as a center where Japanese families farmed and shopped and went to school; the community survives in memory and programs at the Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Institute, and in a few Gardena businesses calling themselves “Moneta.”

Tropico was a valiant little town wedged between L.A. and the southern edge of Glendale. In February 1888, The Times’ society page noted that a Mr. M.O. Ayres and family, from Nebraska, were “wintering in Tropico to escape the rigors of their northern home.” Tropico then was still a town of about 75 houses — it wasn’t incorporated until 1911 — whose town marshal bragged that there was not “a single place where liquor can be obtained in any shape or manner.” About 150 of Tropico’s 860 acres were at one point devoted to growing strawberries.

Tropico’s end began when the costs of running the city grew too high, and in a tug of war for its affections between L.A. and Glendale, the city voted in 1917 to pair up with Glendale, in spite of a warning in the Tropico Sentinel that “Tropico will become the wife” — meaning the inferior — “in this wedding of towns.” Tropico’s favorite son? The acclaimed visionary photographer Edward Weston, who took photos of the town and portraits of its residents, for sale at his studio, $5 for a dozen.

A postcard with a 1903 postmark from Patt Morrison’s collection shows a family on their farm in Hynes, now part of Paramount.

The onetime town of Hynes is now the city of Paramount — well, half of it. Hynes was a riverside dairy town and — hard as it is to believe now — the hay capital of the world, at least by bragging measurement. With the neighboring town of Clearwater, it threw annual hay and dairy festivals. After World War II, as suburbanization made hay on the old hayfields the two joined under a new name — Paramount. They fought over it for almost two years, and it took some Solomonic doing to pull off. The Clearwater Chamber of Commerce and its women’s division balked, and one of those who soothed hurt feelings was Frank Zamboni, Kiwanis Club leader and creator of the charismatic ice resurfacing machine that bears his name.

Hynes had its own national bank, which was irresistible to a quartet of stick-up men in 1919. One of the four was an ex-soldier who, one year before, had been gassed when he was fighting in the battles of St. Mihiel and the Argonne in World War I. He needed the money, he said, to marry his teenaged fiancee.

The never-were cities were called “dream cities,” which was wishful thinking, given that so many of them wound up as nightmares in the wreckage of the 1880s real estate boom.

The outright scams abounded, and few were scammier than Simon Homburg’s. In about 1887, he bought a couple of big hunks of land from the federal government, in mountains on the eastern edge of L.A. County. One section he called Border City, and the other Manchester. They were so inaccessible that the land could only be surveyed by binoculars, and reached, so it was said, by balloon. The views Homburg bragged about were of desert desolation. He haphazardly divided the land into parcels, 12 or 14 lots per acre. Land that cost him 10 cents per lot, he sold for $1 to $250 each, depending on the gullibility of the mark. Cannily, he didn’t advertise the lots locally, where people might know the lay of the land, but to Easterners and even in Europe. He managed to make himself about $50,000.

Hesperia is a High Desert city with a lovely name from Greek mythology, but its origins were savagely mocked by a spiky 19th century pioneer and newspaperman named Horace Bell. Another pioneer, named Joseph Widney, had bought up a lot of land around Hesperia, and Bell parodied, but maybe not by much, the sales techniques of such boom brokers as a “speculative conspiracy against all that was honest.”

Like the land barkers themselves, Bell too laid it on thick about “Widneyville-by-the-Desert.” There, he wrote, promoters “did a little judicious trimming” of the Joshua trees, “then shipped out a carload of cheap wind-fall oranges and on the end of each bayonet-like spike on the yuccas and on each cactus spine they impaled an orange. Suddenly the desert fruited like the orange grove! … The Easterners stood agape at the Elysian sight” and were mesmerized by the spiel about the college, the churches, the sanitarium and the hotel “that would soon surround the central plaza of Widneyville,” along with irrigation canals that would soon grow oranges “as big as pumpkins. There’ll be a fortune in every block, ladies and gentlemen.”

A postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection with a 1934 postmark depicts Whittier Boulevard in Belvedere Gardens in what is now East Los Angeles.

Belvedere Gardens was a development tract around Whittier Boulevard east of downtown that, after World War I, became a neighborhood and a center of Latino life and culture — schools, shops, community and religious events. Like so much of L.A.’s Latino Eastside, including the nearby hamlet of Belvedere, it became encircled by freeways.

Other names may be familiar to you as streets, yet they are the remnants of towns or plans for towns.

Sawtelle, named for a land development company’s manager, is no more, but the modern VA hospital and remnants of the old soldiers’ home remain. And like Moneta, Sawtelle was a deeply rooted neighborhood for Japanese Angelenos.

Sawtelle had a shotgun marriage with L.A. Toward the end of World War I, city fathers resisted Sawtelle voters’ three-margin “yes” vote to joining L.A. So L.A. came in and carted off the city safe, the city seal, and even city hall lightbulbs. Sawtelle’s rump council thereafter met in someone’s home. The battle went on for several years. After the state Supreme Court sided with Sawtelle city fathers, L.A. took its fire hose and municipal furniture and decamped. The brief, sweet victory ended in 1922 when Sawtellians voted by about three to one to return to L.A.’s civic embrace.

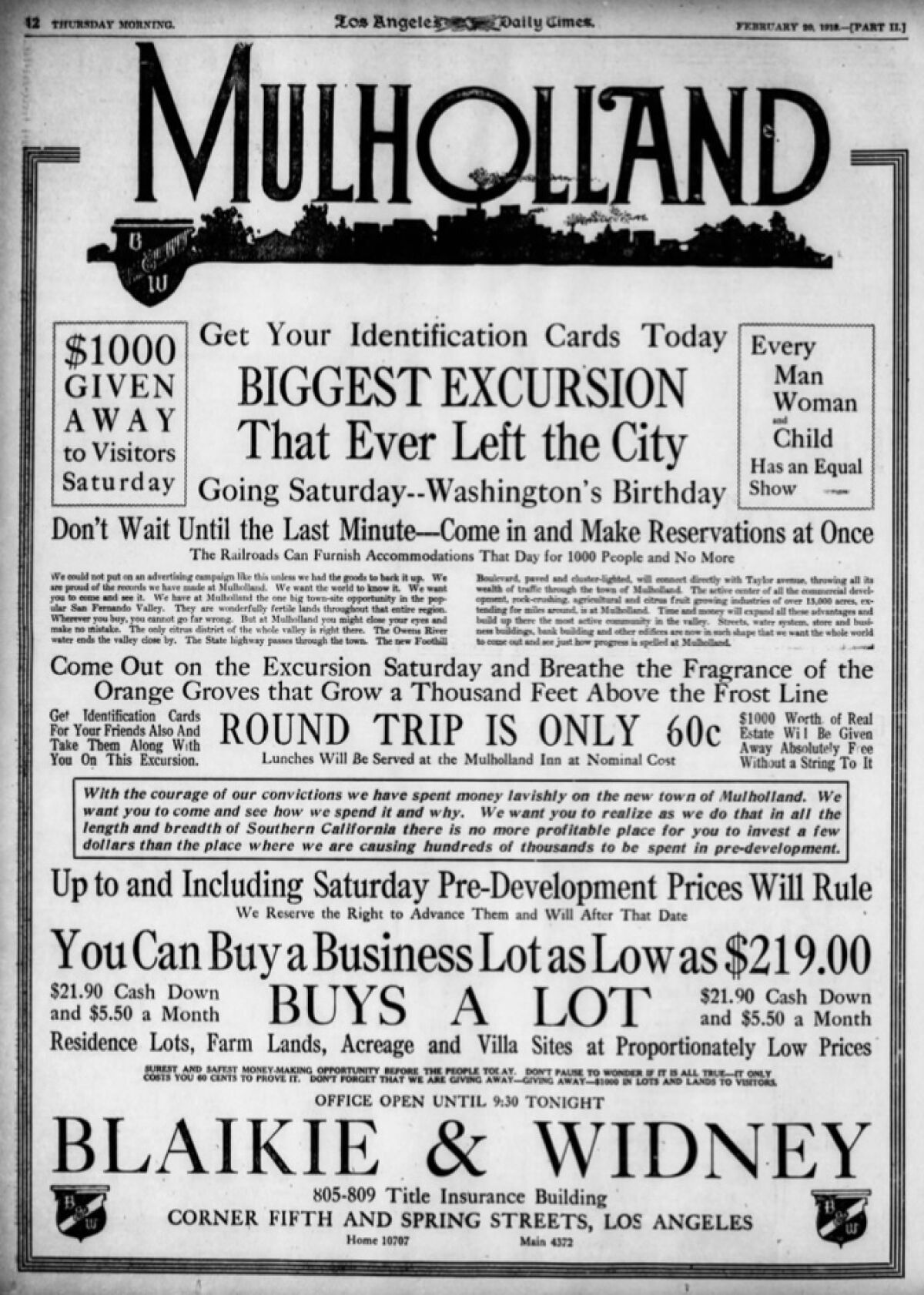

An ad in a 1918 edition of the Los Angeles Times advertises the “new town of Mulholland,” where orange groves “grow a thousand feet above the frost line.”

(Los Angeles Times archive)

The town of Mulholland — well, everyone knows Mulholland Drive, if not the man William Mulholland himself. The town of Mulholland existed mostly in exuberant sales pitches. Nine months before water cascaded to the L.A. end of the aqueduct built by William Mulholland, The Times was already selling the town of Mulholland as “the pay roll town of the San Fernando Valley.”

Lankershim rings a fainter bell, more likely for the boulevard than for the pioneering Lankershim farmers and developers, father and son. The town founded in about 1893 vacillated between names — Lankershim! No, Toluca! — but in 1906, Lankershim won. Until 1927, when the whole shebang became North Hollywood.

The USC College of Fine Arts, now Judson Studios, is seen on a postcard with an early-1900s postmark from Patt Morrison’s collection. Writing on the back asks whether an addressee in Connecticut recognizes the building: “It looks different now though because they have built on.”

Garvanza — a garbled delivery of “garbanzo,” for a local crop — was the name for the pleasant pocket of valley and hills on either side of what is now Avenue 64 in Highland Park, created as a town in 1886 and annexed by L.A. in 1889. Its chief ornament then and now is the sublime stone Church of the Angels, built the same year that L.A. annexed Garvanza, but the divvy put it on the Pasadena side of the street.

Colegrove, a town that abutted Hollywood to the south, bore the name of the founder’s wife, Olive Colegrove. Cornelius Cole was a two-term California senator and confidant of Abe Lincoln’s, and as payment for a victory in a massive land dispute, his client, Henry Hancock, paid him with 500 acres that Cole settled and subdivided. The town was annexed to Los Angeles in 1909, and Cole died in his house in 1924 at 102, the longest-ever-living U.S. senator.

Colegrove’s brief moral panic, in 1904, was triggered when Pearl Morton, a notorious madam whose business address was in downtown L.A., built herself a private, $12,000 house at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Wilbur Street. It didn’t take too many years for a civic cleanup campaign to send her packing for San Francisco’s less censorious neighborhoods.

You know Lordsburg today as La Verne — and Lordsburg College as the University of La Verne.

Lordsburg — you know it as La Verne — was one of those classic “boom-to-bust” 1880s towns, built with a hotel to entice settlers who never came. The hotel was reborn as a religious college, the forebear of the University of La Verne. The town’s founder, Isaac Lord, was himself scammed out of almost $10,000 by a flimflam man nicknamed Rebel George, who promised to invest it in a gold mine and left Lord and a friend holding the bag — a pile of gilded lead pieces.

All of this likely left Lord a cranky man, and when Lordsburg asked its largest landowner for permission to change its name to La Verne, he balked. Only after he died, in 1917, did Lordsburg become La Verne, with a symbolic civic wedding between “Miss Lordsburg” and “Mr. La Verne.”

Owensmouth was the town at the outfall end of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, and a tombstone tribute to Owens Valley, which was left literally high and dry when L.A. brought its water south in 1913. Paradoxically, Owensmouth itself pumped groundwater for its needs and didn’t get any of that aqueduct water until it agreed to hand over its civic keys to L.A. in 1917. It became the neighborhood of Canoga Park. One of the books by Catherine Mulholland, granddaughter of aqueduct engineer William Mulholland, was called “Owensmouth Baby: The Making of a San Fernando Valley Town.”

Whatever the pitch, whatever the hype, it all began and often ended with water.

In the crazed year of 1887, the “specter city” of Chicago Park was laid out in the dry wash of the San Gabriel River — 2,289 lots, reputedly sold for $13 each, in accordance with the eccentricities of the developer. Posters advertising the sales showed steamers merrily plying the imagined waters of the river. But soon enough, as the 1916 “Southern California Quarterly” pronounced, the river “arose in its wrath and converted Chicago Park into a maritime city by washing its soil and silt into the San Pedro Harbor, forty miles away.”

Five years later, those many hundreds of lots of Chicago Park were valued by the county assessor at $1 — for a bundle of five.